I have been describing the amazing churches and religious buildings of the city of Ravenna. Art historians devote whole careers to comprehending such works, but my goal here is rather different. I will rather suggest what we can learn from such places about how Christians for long centuries thought, believed and acted, and how visual arts featured in their lives and their devotion. Just what did all those art treasures mean to them?

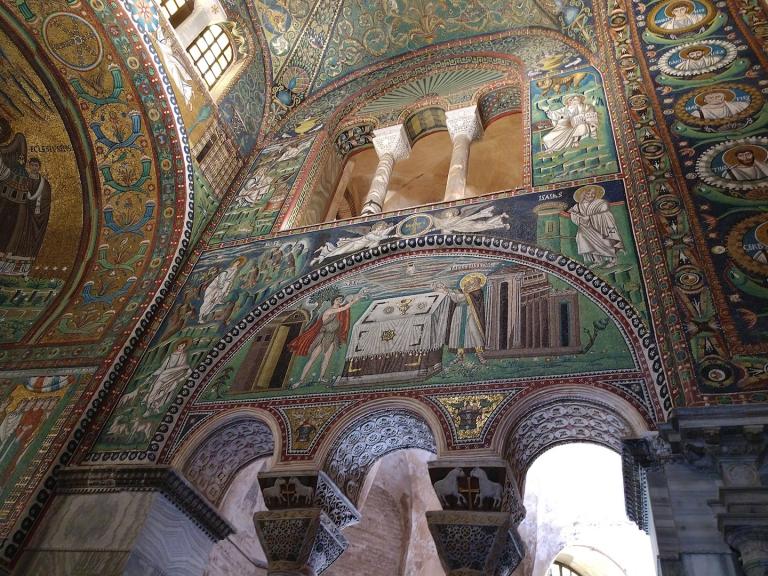

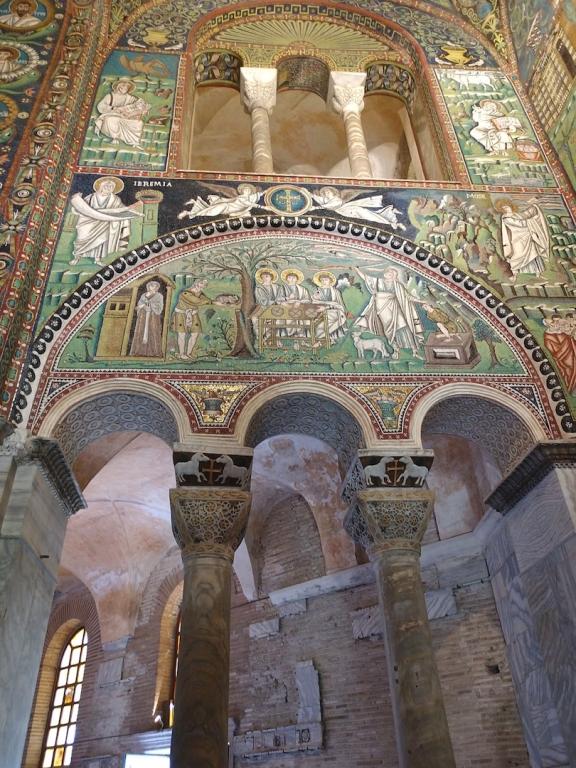

When we look at something like these spectacular mosaics , the most significant point to recall is that these were not intended to be viewed like a painting in a gallery. Certainly a patron might look at a church and take pleasure in the aesthetic achievement, but it was not to be seen in the context of a museum client standing respectfully, perhaps discussing details with a couple of appreciative friends. The art only made sense in the context of performance, of community, and of liturgy. It was meant to create an environment, and the moods appropriate for that world. The art was intended to take you from one place, and move you to another. Above all, it is about time, and the annihilation of time.

To illustrate this, see one glorious detail that might easily get overlooked amidst all the mosaic splendors. Look at the pillars, and the wonderfully subtle shades of the marble.

They are meant to recall clouds – and they do, very strongly.

Now imagine a member of the congregation, participating in a great liturgy, which is a multi-sensory event. There are things to be seen, there is music to be heard, and there is incense to smell. All serve to transport both individual and group to heaven, and the heavenly court. As you look around, you see those clouds supporting the heavenly court, providing the medium on which God and angels move.

There is the central theme. These churches are theaters for liturgy, the goal of which is to move the faithful from earth to heaven, and the artists are imagining that celestial dimension. If you are in heaven, then you know from the Bible the images to expect. You know that the barriers between past, present and future all lie in ruins, and that you are surrounded by the holy dead, by the communion of saints and martyrs. You can see them processing to the divine Throne. Barriers of time have vanished.

And of course the court is patrolled by its angels and archangels. You see them there, and learn to recognize their forms.

This sense of dislocation is powerfully evident in the baptisteries, which were such an essential component of the great church complexes. This was still a time when baptism was intended for adults, who received the sacrament after instruction, usually culminating in the Easter liturgy. When you were baptized, when you stepped into the waters, you saw the meaning of the new life spread around you. You looked up to see the Baptism of Christ, surrounded by the apostles, and the foundation of that church. This was not merely a historic event that occurred five or six centuries before. It was – is – now. It did not happen in Palestine. It is happening now, here, in northern Italy.

In other ways too, those apostles were still present. When modern churches think of bishops, they might imagine bigwigs or bureaucrats who are often removed from the real life of the parish, which revolves around priests or pastors. That was absolutely not the case in this era. Bishops were direct successors of the apostles, their earthly representatives. Commonly, the sequence of bishops ran through martyrs, possibly of quite recent date. Bishops were rooted in blood. Bishops were the church. Bishops were primarily responsible for performing the Eucharistic liturgy, as well as the baptismal ceremonies.

That issue of holy founders posed a dilemma for relative upstart cities like Ravenna, which only entered its age of glory after 400. The city compensated by glorifying the allegedly early saint and martyr Apollinaris, who was supposedly connected to Peter himself.

The same lessons of long continuity emerge from the Eucharistic sacrifice that was the central fact of liturgy, and the primary vehicle uniting earth and heaven. Repeatedly in the churches, around the altars, we find Old Testament stories of sacrifice that directly prefigure that of Christ. These included, for instance, the tales of Abel or Isaac.

Old and New Testaments were brought together in the story of Melchizedek, King of Salem, who brought out bread and wine, and who was the priest of El Elyon, the most high God; and who was another prototype of Christ himself.

Abraham’s story is also recalled in the visit of the three angelic strangers. Early and medieval Christians loved this story because, for them, it so clearly located the Trinity in the Old Testament itself.

We sometimes say that such images were intended to constitute the “Bible of the Poor,” a means of instructing the illiterate about the truths of faith. Yes, that might be one element, although literacy levels were far higher in the era that those churches were built (and Ravenna itself was a bureaucratic/military/ecclesiastical center). But a far more central goal was to keep people’s minds fixed on their present location in time and space, at once residents of earth and heaven. Rather than the Bible of the Poor, you might think of it as a giant sign declaring YOU ARE HERE.

Through the liturgy, through the Eucharist, humans are in the presence of Christ, whom they encounter in different forms.

I discussed the purposes of liturgy in another column, where I formulated “Nine Laws” that I thought summarized the ideas at work. Because they speak quite well to my present theme, let me just give the subheadings here:

- Liturgy takes us out and puts us in

- Liturgy unites, making many one

- That unity crosses boundaries of time and space

- Liturgy uses action to declare and reinforce common belief

- Liturgy tells stories in ways that make us live them

- Liturgy uses performance to tell stories

- Liturgy unites and binds things that otherwise are wholly separate

- Liturgy consecrates time — or else time consecrates liturgy

- Liturgy allows earth to become heaven, however briefly

If you are interested, you can see my arguments in more detail.

But that is what makes religious art distinctive: it is meant to be lived.

CREDITS: all photos taken by myself, with my cellphone.