I have been writing about a recent visit to Ravenna, a place that can have a profound impact on the unsuspecting soul. Let me describe this, and suggest that the city may shortly be preparing for yet another kind of global spiritual event.

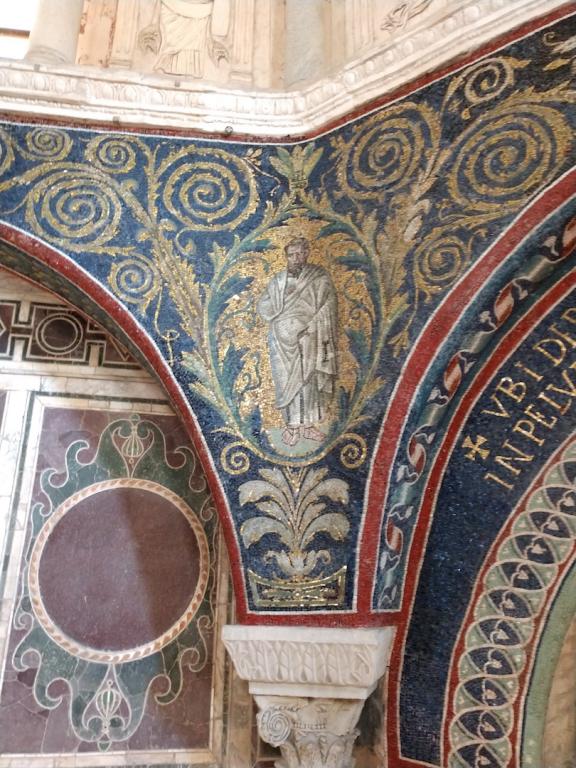

Through the nineteenth century, foreign authors visited Ravenna, and some were moved to write about it, often in really bad verse (I’m looking at you, Oscar Wilde). The number of visitors swelled in the early twentieth century, and two authors in particular made the city the basis of genuinely fine literature. One was W. B. Yeats, who visited in 1907, and was stunned by the mosaics. After a long gestation, those images surfaced in his Sailing to Byzantium, where the author is overwhelmed by the vibrant signs of youthful vitality he sees around him: that is no country for old men. Instead, he seeks refuge in the eternal, hieratic images of Byzantium, as he had witnessed in Ravenna: “O sages standing in God’s holy fire, as in the gold mosaic of a wall.”

The other literary giant in the city about the same time was Russia’s Aleksandr Blok, who in 1909 wrote one of his greatest works in the poem Ravenna. One brief sample:

The burial halls are silent,

Their thresholds shady and cold,

Lest the gaze of Blessed Galla’s black eyes

Should awake and burn through the stone.

You will see many diverse translations of this poem, of wildly varying quality, as it is singularly difficult to turn into comprehensible English. As always with Blok, it is tough to get the mood and tone just right. But like Yeats, Blok was overwhelmed by the eternal stillness of the city, the air of holy, meditative silence, and the distance from frenetic modernity.

I stress, writers of this age were not making some wholly new discovery of the Byzantine past. That revival was already well under way in the mid-nineteenth century, and it had a special impact in architecture. Neo-Byzantine styles were very popular across Europe, partly for the linkage they suggested to very early Christian and Roman-Christian antiquity. As Blok and Yeats were reaching Ravenna, London had recently consecrated its superb contribution to “Byzantine” style in its Westminster Cathedral (built 1895-1903). But such writings did contribute to a revival of interest in Byzantine art and style, in mosaics and icons, and the whole spiritual environment they suggested.

All of which brings me to Ravenna’s upcoming presence in the headlines, and again, it has a great deal to do – shall we say – with eternity, and with culture. Despite all the attention we inevitably pay to Ravenna as a shrine of Late Antiquity, the city attracted later celebrities. One was Dante Aligheri, whose life was marked by so many factional struggles. In 1318, he accepted the invitation of a local prince to take up residence here, and it was in Ravenna that he completed the Paradiso. He died in September 1321, and is buried in what is now the church of San Francesco, in a tomb that is far from worthy of him.

Ah yes, 1321, an anniversary that we are about to commemorate. Already, Italians are preparing to celebrate this historic 700th anniversary, in what should be a national festivity of Italian culture. Florence will obviously be at the fore, but Ravenna will be hard to avoid. Was it not the source of Paradise itself?

It will be interesting to see how the English-speaking world addresses that whole Dante commemoration. Quite apart from the incalculable influence of the Divine Comedy on the whole of literature, it has played a critical role in Christian thought, art, and culture. Anyone planning for 2021 should take full account of Dante’s impact on some pivotal figures in modern Christian literature, notably Charles Williams and Dorothy Sayers. To quote T. S. Eliot, “Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them. There is no third.”

Excuse me, I have an anniversary party to plan at Baylor.