I teach and research sermons. Two weeks ago, on September 11, I had the privilege of preaching my first sermon at Truett seminary. I am so thankful for seminaries like Truett which affirm and actively support women in ministry. Although my sermon text stands as I originally wrote it (including the section I just jotted notes and filled out while preaching), I have included citation links. Even preachers need to make sure that their sermons are built on reputable stories and information.

I teach and research sermons. Two weeks ago, on September 11, I had the privilege of preaching my first sermon at Truett seminary. I am so thankful for seminaries like Truett which affirm and actively support women in ministry. Although my sermon text stands as I originally wrote it (including the section I just jotted notes and filled out while preaching), I have included citation links. Even preachers need to make sure that their sermons are built on reputable stories and information.

“God be in my head and in my understanding. In mine Eyes, and in my looking. In my mouth, and in my speaking. In my heart, and in my thinking. At my end, and in my departing.”

Folger Library MS V.a.482, 16th Century Prayer Book

The Faith to Touch Jesus: A Sermon Delivered September 11, 2018, at Truett Seminary

Luke 8:40-48

“Now, when Jesus returned, a crowd welcomed him, for they were all expecting him. Then a man named Jairus, a synagogue leader, came and fell at Jesus’ feet, pleading with him to come to his house because his only daughter, a girl of about twelve, was dying.

As Jesus was on his way, the crowds almost crushed him. And a woman was there who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years, but no one could heal her. She came up behind him and touched the edge of his cloak, and immediately her bleeding stopped.

“Who touched me?” Jesus asked.

When they all denied it, Peter said, “Master, the people are crowding and pressing against you.”

But Jesus said, “Someone touched me; I know that power has gone out from me.”

Then the woman, seeing that she could not go unnoticed, came trembling and fell at his feet. In the presence of all the people, she told why she had touched him and how she had been instantly healed.

Then he said to her, “Daughter, your faith has healed you. Go in peace.”

Seventeen years ago today I had just sat down in a passenger car on a train in Hereford, England. I was 26 and had been in England for over two months working on my dissertation. That particular morni ng I had been working in the archives of Hereford Cathedral reading a fifteenth-century marriage sermon. I still vividly remember my handwritten page of notes. At the top of the page, printed as neatly as I am capable of, ran the heading “Hereford Cathedral MS O.III.V, September 11, 2001.

ng I had been working in the archives of Hereford Cathedral reading a fifteenth-century marriage sermon. I still vividly remember my handwritten page of notes. At the top of the page, printed as neatly as I am capable of, ran the heading “Hereford Cathedral MS O.III.V, September 11, 2001.

A woman sat down next to me. I honestly don’t remember what she looked like. But I remember what she said. “Dear, are you American? Did you know America has been attacked?!? The White House is in flames!!”

I just stared at her, unable to comprehend her words. I think she thrust a paper at me while she kept talking, excitedly gesturing and asking me questions (although I have no memory of answering her). It wasn’t until I reached the main train station that I began to finally piece together what had happened. The TV screens flashed terrifying images.

Soon thereafter, I found myself heading to a church I loved. Its stone steeple of a modern Anglican church with deep medieval roots was just minutes away from the Birmingham train station I traveled through so often. I still am not sure if I just managed to hit it at the right time or if they were holding a special service. But, as I entered the nave, I could hear the strains of “Come, just as you are to worship, Come, just as you are before your God.”

I had been attending this church for several weeks. I loved the diversity of people, the blend of African worship music with nineteenth-century hymns, the modern screen hanging from the 18th century stone pillars. It is funny the things I don’t remember about that day. I don’t remember if I was standing or sitting. I don’t remember if I was crying, although I think I must have been because the woman next to me handed me Kleenex. I really don’t remember much about the service at all—except for two things. I remember the song—“Come, just as you are to worship.”

And I remember one of the pastors running down the aisle toward me (remember, I had been attending for several weeks and he knew I was American). He asked if I was okay. Almost immediately, though, he took it back. I am sure my face told him all he needed to know. “No, of course you aren’t okay.” Then he said something that I have never forgotten. “Sister, reach out to Jesus,” he said. “We all need his power today.”

I don’t know for sure, but I have always suspected that the pastor was alluding to Luke 8. Remember the text:

Then the woman, seeing that she could not go unnoticed, came trembling and fell at his feet. In the presence of all the people, she told why she had touched him and how she had been instantly healed.

Then he said to her, “Daughter, your faith has healed you. Go in peace.”

Maybe it was his devotional that day; maybe God just brought it to his mind at that moment of crisis.

Whatever the reason, I have never forgotten the words of that pastor.

On the one hand, it isn’t strange that I remember this encounter. Like so many Americans, I will probably never forget September 11, 2001—neither the tragedy nor the details of where I was and what I was doing.

On the other hand, however, my remembrance isn’t just because of the terrible events. It is also because of this pastor’s words, reminding me on a day when all hope seemed lost about a woman who had the faith to reach out and touch Jesus.

Now, as someone who reads a lot of late medieval English sermons, I have found that the way we as Christians in modern America approach the woman of Luke 8 isn’t the same as medieval preachers (at least the fourteenth and fifteenth century sermons that I read).

Like any good, well-trained scholar, when I need to do research, I turn first to google. Using the google NGram reader, I found that our interest in the woman of Luke 8 has been mostly in decline since the 19th century. Isn’t that interesting? I also found that when we preach, teach, and write about this woman, we often focus on how she is sick and frail; desperate; ceremonially unclean; an outcast. Indeed, listen to how Bible Gateway frames a discussion of this woman with its opening sentence. “This sick, anonymous woman must have been emaciated after a hemorrhage lasting for twelve years, which rendered her legally unclean.” A website which receives more than 1.6 billion pageviews and more than 160 million readers every year, Bible Gateway is a powerful shaper of the modern Christian perspective. When it highlights this woman as “sick,” “emaciated,” “unclean,” “modest,” and “humble,” it is not a surprise to me that we find this description echoed in devotionals, sermons, and evangelical texts. You see, Bible Gateway presents this woman in a way that fits evangelical assumptions about gender—a woman weakened by her female body.

This isn’t what sermon authors of late medieval English sermons, like John Mirk’s Festial, focused on. Instead of her weakness, they focused on the strength of her faith.

This is really striking to me.

Out of the roughly 25 New Testament passages on faith repeatedly preached in late medieval English sermons, half of them are about women of faith—specifically, three women of faith: the woman with the alabaster jar (Mary Magdalene to medieval Christians), the woman of Canaan, and the woman with the issue of blood. These women were heralded as exemplars of strong faith. Indeed, in one late medieval English sermon manuscript, the woman of Canaan was described as a better example of faith than the Apostle Paul. While God did not answer Paul’s prayer for his thorn in the flesh to be removed, proclaimed one late medieval sermon text, God listened and answered the prayer of the woman of Canaan. The faith of a woman was highlighted as even stronger than the faith of a male apostle.

This focus on the strength of the woman’s faith makes better sense to me. Let’s look back at Luke 8:

–the parable of the sower (the good seed are those who hear the word of God and follow it, producing fruit)

–Jesus declaring that his family are those who hear and do the word of God

–Jesus rebukes the disciples as not having faith, “though seeing, they don’t see; though hearing, they don’t understand”

–and then enters the woman with the flux of blood. Mark 5 tells us that when she heard of Jesus, she believed he could heal her. So she reached out and touched him. Jesus makes it clear that she—unlike the disciples in this passage—truly gets it. “Daughter, your faith has healed you.”

I really like what Sarah Bessey has to say about the word “daughter.” She is preaching on Luke 13, not Luke 8, but the passage is also about Jesus healing a woman. Listen to what she says.

“When Jesus healed the woman who was bent over and crippled in Luke 13:10-16, he did it in the synagogue, in full view. When the Pharisees pushed back at the healing because it took place on the Sabbath, he called them hypocrites because they would rescue and ox or a donkey on the Sabbath, but they couldn’t see the glorious Sabbath work of rescuing a “daughter of Abraham” on this day. And here’s my favourite part: Jesus called her “daughter of Abraham,” which likely sent a shock wave through the room. It was the first time that phrase had been spoken. People had only ever heard “son of Abraham”— never daughters. But at the sound of Jesus’ words, “daughter of Abraham” he gave her a place to stand alongside the sons. In him, [women] are part of the family, we always were.”

It is more than coincidental that Jesus described his family in Luke 8 as “those who hear God’s word and put it into practice” and then calls the woman who touched him “daughter.” She heard and understood; and this faith healed her, body and soul.

I have been in the ministry for over 20 years with my husband. We have seen, heard, and experienced so many things. We have experienced great joy, and we have experienced gut-wrenching pain and betrayal. Like the woman who endured year after year of sickness, the discouraging grind of ministry has sometimes (often?) worn us down.

Which is why I think the story of this woman is so important to share with you—as future pastors and ministers, missionaries and teachers, lawyers and social workers. The woman in Luke 8 understood something that not even the disciples had yet figured out—that Jesus would never fail her. All she had to do, despite the hopelessness of her circumstances, was reach out and touch him.

May God give you all the faith of this woman.

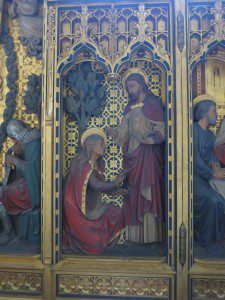

*the images are both medieval (St. Helen’s Bishopgate and Notre Dame), but they are both of Mary Magdalene recognizing the Resurrected Christ. Unfortunately I do not have any medieval images of the woman in Luke 8.