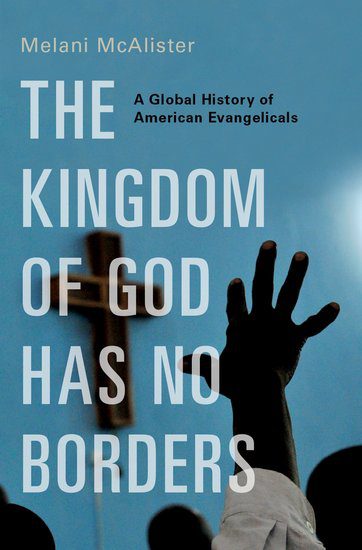

Back in August I interviewed Melani McAlister, a professor of American studies at George Washington University, for Christianity Today. Her new book, The Kingdom of God Has No Borders, is just out with Oxford University Press. Below are some excerpts of my conversation with her. If you want to read more, click here for the rest of the interview.

***

David: How have encounters in the Majority World made American evangelicals more liberal in some ways and more conservative in others?

Melani: American evangelicals have often given donations to charity. That’s not new. But as they encountered economic insecurity, political instability, health crises, and refugee situations, they began to realize that global poverty couldn’t be solved through charity alone. In 2005 American and European evangelicals prayed outside the G8 Summit for debt relief for Africa. They were saying, “This is a political issue that needs a political solution.” This was because they had been talking to and reading the work of people in Africa saying similar things.

Melani: American evangelicals have often given donations to charity. That’s not new. But as they encountered economic insecurity, political instability, health crises, and refugee situations, they began to realize that global poverty couldn’t be solved through charity alone. In 2005 American and European evangelicals prayed outside the G8 Summit for debt relief for Africa. They were saying, “This is a political issue that needs a political solution.” This was because they had been talking to and reading the work of people in Africa saying similar things.

On the other hand, African leaders have tended to be more conservative on issues like ordaining women or officiating at lesbian and gay weddings, and American evangelicals have treated their voices as the authentic ones. They say, “We hold this conservative position, and we’re in alliance with our African brothers.” This has put mainline Protestants in a real bind because they end up being portrayed as neo-colonialists, excessively white, and not in solidarity with people of color.

What do you mean when you describe Americans as “enchanted” by Africa?

I’m describing feelings of emotional connection, investment, and even solidarity with Africa that are cultivated by short-term missions or requests for donations from international charities. We see among American evangelicals—and other Americans too—a fear that our modern industrialized society has taken something away from us, made our lives too materialistic, too rationalist, too evacuated of meaning. People often present Africa as a kind of antidote, as a space where Christians are more authentic or emotionally rich, where Christianity is more saturated by the spiritual.

I saw this a lot in Sudan, where I did a short-term mission with a church, and in Cairo with InterVarsity students working with Sudanese refugees. In both cases, Americans saw the Sudanese as being close to Jesus in a way that they were not. But there’s a really fine line between respecting and valuing people across cultures and demanding that people embody something that you want yourself. This is not just an evangelical problem. We see this, for instance, in the persistent idea of the noble savage, where genuine admiration also has a kind of imperialist demand that people be pure and simple, so that you as a Westerner can visit them to find yourself renewed by them in some way. Enchantment includes the potential for respect and connection but also the real problem of demanding things in other people.

You observe that American evangelicals wanted the objects of their missions work to be “desperate but not hopeless, eager but not competent.” To what extent does this reflect a lingering colonialist view of Africa?

You observe that American evangelicals wanted the objects of their missions work to be “desperate but not hopeless, eager but not competent.” To what extent does this reflect a lingering colonialist view of Africa?

There are still very real remnants of neocolonial attitudes among American evangelicals. But they are far from unique in this. We can see something similar in mainstream American culture. One thing that surprised me, though, was how neocolonialism is a prevalent category of analysis for some evangelicals. The scholar Soong-Chan Rah has a really sustained critique of the Western mindset of American evangelicals. An African Christian leader, Tokunboh Adeyemo, organized the Africa Bible Commentary with dozens of other scholars from Africa; they wrote about the Bible from their own perspective to counter what they saw as colonial or irrelevant interpretations from the West. There have been many people in the global evangelical community, people of color in the US, and some white people as well who have spoken about this continuing problem of a colonial mindset.

You grew up Southern Baptist, but you now call yourself an outsider to the movement. What was it like to travel abroad with American Christians?

I did two short-term missions. At one point, I was interviewing a young woman with InterVarsity who was talking about all the Sudanese Christians she had met in Egypt who were refugees. I asked her what she had learned. She looked at me and said, “Melani, heaven is going to be packed!” She was realizing that the world she saw as her own, her Christian world, was much bigger than she had ever imagined.

In general, I was struck by how hard people were working to understand situations that were not their own. Both the InterVarsity students I hung out with in Cairo and the church group from Wisconsin I went to South Sudan with were really aiming to get beyond their own assumptions. Were they 100 percent successful? No. That’s a hard thing to do, and I’m not sure how many people are ever that successful at it.

So I was impressed by the openness of the people I went to Cairo and Sudan with. But in a larger sense, my travel with Christians over the last decade—meeting and interviewing scores of people and reading their work—has led me to a broader conclusion, which is that there are elements in evangelical religious experience that cultivate exclusivity and a sense of nationalism, religious superiority, gender conservatism, and racial barriers. There are also elements that empower cosmopolitan connection, a sense of social justice, and openness to difference. I have seen both at work at every historical moment.