On September 27, 1969, the Society of Experimental Test Pilots (SETP) named the 67-year old Charles Lindbergh an honorary fellow, and invited him to address its banquet in Beverly Hills, California. Well into his latter-day career as an advocate for environmental protection, Lindbergh issued a warning:

We cannot escape the fact that while science, industry, and commerce are progressing, the environment of life is breaking down. We pilots have had an unique opportunity to watch this breakdown — the stripping of forests, the erosion of land, the pollution of water and air; the destruction of cities at one time and place, and their megalopolizing at another…. We now find that the expanding frontiers of aviation have overtaken the evolving frontiers of life, and that failure to integrate the two would almost certainly be catastrophic.

Among the “we pilots” he addressed that night was his table mate: astronaut Neil Armstrong, just two months removed from becoming the first human being to set foot on the Moon. We don’t know much of what two of the most famous Americans of the 20th century discussed that night, but Armstrong’s hero reportedly shared one piece of advice: never sign autographs.

According to Armstrong’s authorized biographer, James Hansen, the two men had first met a year before, just before Apollo 8 became the first manned spacecraft to reach and orbit the Moon. Armstrong gave Lindbergh and his wife Anne a tour of the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida. They remained correspondents, with Lindbergh later asking Armstrong if he “felt on the Moon’s surface as I did after landing at Paris in 1927—that I would like to have had more chance to look around.”

Armstrong ultimately concluded that the achievements of 1927 and 1969 “are probably more unlike than alike.” But the comparisons between the two men are impossible to avoid. NASA’s director of flight operations, Chris Kraft, told Hansen that “we just knew damn well that the first guy on the Moon was going to be a Lindbergh… And who do we want that to be? The first man on the Moon would be a legend, an American hero beyond Lucky Lindbergh, beyond any soldier or politician or inventor.” To Kraft, Armstrong was the easy choice: “Neil was Neil. Calm, quiet, and absolute confidence. We all knew that he was the Lindbergh type. He had no ego…. Neil Armstrong, reticent, soft-spoken, and heroic, was our only choice.”

But the similarity runs more deeply than the two men fitting a certain ideal of the quiet, unassuming hero. Both Armstrong and Lindbergh, we would say in 2018, were “spiritual, but not religious.”

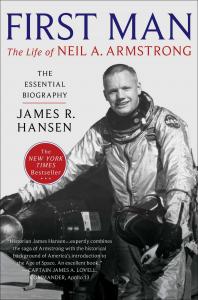

That’s the subject of my in-the-works biography of Lindbergh. You can read more about his spiritual journey here and here. But what of Armstrong, back in the public eye again because of the new movie, First Man?

I’ll be curious to see how that film addresses religious themes. In his review for America, critic John Anderson concludes that director Damien Chazelle “was entertaining cosmic questions in the making of his film” — but also “played for laughs” a reporter asking Armstrong if he felt closer to God during the near-disastrous Gemini 8 flight in 1966.

First Man is based on the work of Hansen, who notes that there is no shortage of strange conjectures on the subject of Armstrong’s belief (or lack thereof) in the supernatural: that the Moon landing was part of a Masonic conspiracy; that Armstrong verified Erich von Däniken’s theory that extraterrestrial beings had visited Earth as “ancient astronauts”; and, most famously, that Armstrong thought he heard the adhan, the Muslim call to prayer, while walking the lunar surface and converted to Islam.

But if none of those theories is credible, it’s also clear that Armstrong was not an avowed Christian. At least, not one in the mold of his Apollo 11 crewmate Buzz Aldrin, who celebrated Communion in the lunar module and was an elder at the same Presbyterian church that John Glenn attended. Nor James Irwin, who followed Armstrong and Aldrin to the Moon two years later and then spent the rest of his life as an evangelist. (His Christian foundation took its name from “High Flight,” the poem I mentioned in an earlier post; its pilot-narrator concludes by touching “the face of God.”) Armstrong’s Gemini 8 co-pilot David Scott went to the same Episcopal church as Frank Borman, the Apollo 8 commander who joined Jim Lovell (Presbyterian) and Bill Anders (Roman Catholic) in reading the first verses of Genesis as they orbited the Moon on Christmas Eve.

But when Neil Armstrong applied to NASA, he wrote simply that he had “no religious preference.”

Armstrong’s rather devout mother, Viola, recalled feeling that her newborn first child had been “completely fashioned by God, truly a precious blessing to us to have, to hold, to cherish, to love, and to teach the beauty of life.” She arranged to have Neil baptized in the Armstrongs’ living room, by the same minister who had married her and Stephen Armstrong: “In my heart I dedicated him to God, and promised I would do my best to rear him according to God’s Holy Word.” The Armstrongs had met in a Reformed youth group, but she wrote to Rev. Charles Sloca, a Methodist pastor in Iowa, that her husband’s “love of the Master never seemed to be as deep as mine.” Hansen adds at this point: “The same was true for Neil, Viola knew, though she always found that harder to admit to herself.”

She recalled that her son “began wondering about the truth of Jesus Christ” in high school, perhaps under the influence of an especially compelling science and math teacher. When he asked to lead a Boy Scout troop at a Methodist church in the late 1950s, Armstrong completed the religious affiliation space on the application form with the word “Deism.” Hansen concludes that

She recalled that her son “began wondering about the truth of Jesus Christ” in high school, perhaps under the influence of an especially compelling science and math teacher. When he asked to lead a Boy Scout troop at a Methodist church in the late 1950s, Armstrong completed the religious affiliation space on the application form with the word “Deism.” Hansen concludes that

by the time Armstrong returned from Korea in 1952 he had become a type of deist, a person whose belief in God was founded on reason rather than revelation, and on an understanding of God’s natural laws rather than on the authority of any particular creed or church doctrine.

In 1969 Madalyn Murray O’Hair tried to claim Armstrong as a fellow atheist. Armstrong denied it in an interview with Walter Cronkite, the month before he shared a table with Lindbergh: “I don’t know where Mrs. O’Hair gets her information, but she certainly didn’t bother to inquire from me nor apparently the agency, but I am certainly not an atheist.” When Cronkite noted the “no religious preference” entry on Armstrong’s NASA application, the first man on the Moon explained that he simply meant that he had no “acknowledged identification or association with a particular church group at the time.” He seemed to have said little more on the subject between then and his death in 2012.

Viola Armstrong confessed to Rev. Sloca that her son’s decision not to raise his own children as Christians “causes a million swords to be pierced through my heart constantly.” But she still believed that “God gave him a mind to use and maybe destined him to the work he has been doing… His thinking is big and his thoughts are far reaching. He seems to be inspired by God, and speaking his Will. For this I am over and over thankful.”

And that brings us back to Lindbergh… Just before Christmas 1980, some of his closest Christian friends celebrated “The Faith of the Lone Eagle” in a special service at the church near his grave in Hawaii. Though Lindbergh never joined a church and found himself uncomfortable with organized religion of any sort, his friends described him as a “man of faith” who “believed that God was in all of us” and is now “with the Good Lord, and will [be] always.”

So if I can close on an unresolved note… However understandable their reasons, have Christians like Armstrong’s mother and Lindbergh’s friends made too tidy a meaning of such “spiritual, but not religious” lives? Or do their interpretations suggest how Christians can perceive God at work beyond the church?

In an upcoming post I’ll get further afield from Lindbergh and consider more broadly the religious history of the Space Race.