It’s Election Day, but I thought I’d steer clear of politics and talk about something less controversial: what bothers me about fellow evangelicals’ opposition to women preaching.

Almost as long as I’ve been alive, the two evangelical communities that I know best have only ever affirmed the full participation of women in the church. I’ve spent almost all of my career teaching at Bethel University, whose seminary first awarded an M.Div. to a woman in May 1976, when I was just a few months old. That same year, my home denomination, the Evangelical Covenant Church (ECC), voted to ordain women. In fact, Bethel’s trailblazing seminarian, Carol Shimmin Nordstrom, was a delegate at the ECC annual meeting that year and soon became one of the first women ordained by the Covenant. From early childhood to my adult career, I’ve always known evangelical women to be actively engaged in preaching, as well as teaching, evangelism, and social action.

1976 was a turning point for my evangelical communities. But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Bethel and the Covenant still circumscribed women’s roles, other evangelicals were already affirming women’s right to preach and evangelize. Writing in the same year as the Bethel/ECC changes, historical theologian Donald Dayton went so far as to argue that “it is Evangelicalism that next to Quakerism has given the greatest role to women in the life of the church.”

For example, Dayton points to the early decades of the Evangelical Free Church of America (EFCA). While the E Free are now very much on the conservative end of this spectrum, some of its founding fathers argued strenuously in favor of affirming the ability of women to proclaim the Word of God.

Like the Covenant Church and Bethel, the EFCA emerged out of the pietistic revival that swept through 19th century Scandinavia and then crossed the Atlantic in ships’ full of immigrants bound for North America. As some of the Swedish-American Pietists organized a “Mission Covenant” in 1885, those more wary of denominationalism stayed apart, with their “free churches” only loosely organizing. In 1950 the Swedish Evangelical Free Church merged with its Norwegian-Danish counterpart to form the EFCA.

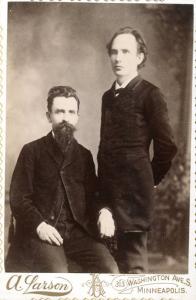

In No Time for Silence, Janette Hassey points to several examples of how women played key roles in the early days of Scandinavian-American Free churches. Josephine Princell not only headed the Swedish department of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, but fulfilled Frances Willard’s wish to see women in the pulpit: she preached in Minneapolis when her husband, John Gustaf Princell, was absent. She also taught at the Swedish Bible Institute (a forerunner to today’s Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) after her husband became its leader. Scandinavian-American Free schools educated women for ministry, and their churches and conferences ordained preachers like Christina Carlson and Ellen Modin. “God is with her and she speaks, anointed by the Holy Spirit” J. G. Princell wrote in 1888 of another such pioneer, Nelly Hall, “while many preachers are so dry they creak.”

So were these Scandinavian-American Pietists theological liberals, blithely dismissive of biblical prescriptions that women keep silent?

On the contrary, early Free Church leaders like Princell were evangelicals, if not fundamentalists. They exemplified how theologically conservative Protestants in the late 19th century affirmed women’s roles in the church precisely because of their commitment to the authority of Scripture and to the Great Commission.

There’s no better example of the theme than Fredrik Franson, second only to J.G. Princell among the Swedish founders of the E Free. After coming to the United States in 1870, meeting Dwight L. Moody, and reading John Henry Darby, Franson dedicated himself to evangelizing the world before what he expected to be Christ’s premillennial return. Dividing his time between Europe and the United States, he founded what’s now The Evangelical Alliance Mission in 1890.

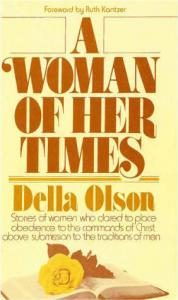

This same fervor for evangelism led Franson to write an essay entitled Prophesying Daughters. “What the Bible says about the woman’s place in evangelistic work and prophesying,” he began, “is a very important question, especially in our day, when, not only here at home but also in the heathen lands, so many doors are open for mission work.” In her 1977 collection, A Woman of Her Times, E Free writer Della Olson concluded that “[i]t would be impossible to fully evaluate the far-reaching influence” of Franson’s pamphlet.”

(Originally in German, then translated into Swedish in 1896, Prophesying Daughters was later translated into English by Sigurd Westberg, a missionary and biblical scholar who helped translate the Bible into Lingala. It was published by the Covenant Church after the 1976 vote for women’s ordination — alongside a reprint of the section of Don Dayton’s book that I quote at the beginning and end of this post.)

Franson’s essay started with practical concerns: ”The [missions] field is thus very large, and when we consider that nearly two thirds of all converted persons in the world are women… the question of woman’s work in evangelization is of highest importance.” (Also, they could “most inexpensively carry on the work.”) Of course, even evangelical pragmatism had to bend the knee to biblical authority. But, Franson decided, “if there is no prohibition in the Bible of public service by women, either in political franchise or in working in the service of the Lord through evangelism, then we stand face to face with the fact that the devil has succeeded in excluding nearly two thirds of the total number of believers-damage to God’s work so great that it can scarcely be described.”

He found no such prohibition. After citing several Old Testament examples of women serving as prophets and leaders, Franson emphasizes that the “message of [Jesus’] resurrection, which was to be preached to the farthest boundaries of the earth, was first proclaimed by a woman” (Mary Magdalene). He then comes to Pentecost, and the fulfillment of Joel’s prophecy that “your son and your daughters shall prophesy…. Even upon the menservants and maidservants in those days I will pour out my Spirit” (2:28). As Franson considers the New Testament examples of women like Phoebe and Junias, he dismisses the idea that Jesus entrusted the proclamation of his Gospel to only half his followers:

Many people ask: If Jesus had wanted to use sisters in the work, why did he not send any out? With the Bible open before us, we can reply: If Jesus did not want to use sisters, why did he send out, both before his resurrection and lastly on the day of Pentecost, so many sisters with the glad tidings?

Indeed, Franson thinks Scripture is generally “so clear regarding the right of women to public evangelistic work, it is remarkable that the only other passages (1 Timothy 2:12,13 and 1 Corinthians 14:3,4) can be given such a contradictory meaning.” But without denying the inspiration of these verses, he warns that “it is through this process of grounding a doctrine on one or two passages in the Bible, without reading them in context, that heresies arise.” (On the obsession of some more recent evangelicals with these verses, see Beth’s earlier series on how medieval Christians read the Apostle Paul.)

After painstaking exegesis of 1 Timothy 2, Franson decides that 1 Corinthians 14:34 (“The women should keep silence in the churches”) is the only verse that “really appears to be against the public appearance of women in the congregation.” And he warns that even this sentence of Paul’s is liable to being read out of context. In the end, Franson has little doubt that women are called and gifted to publicly proclaim the Gospel of Christ:

That unclear, somewhat clouded passage in 1 Corinthians 14:34 ought not and need not be understood in such a way that it comes into disharmony with other plain words of God which establish it as a clear truth that brothers and sisters are permitted to proclaim the pure Gospel for the revival of the unconverted ad for the exhortation, comfort, and sanctification of God’s children and that no one should be hindered in this. God be praised that this interpretation is winning more and more acknowledgement, so that in our day in many lands large numbers of [women] are going out into home mission work as well as into mission work in heathen lands. Let us thank God that the bread of life is being brought to a dying world.

Given his initial focus on the “heathen lands” of Asia and Africa, it’s notable that Franson also praises God for sending women into “home mission work” — that is, evangelism in unchurched America. Here he does warn such evangelists “not to try, especially publicly, to defend preaching by women… It is enough that they themselves have assurance in their own hearts of the Word of God, that they have the right to evangelize and don’t need much discussion of the subject.” But that’s plainly not because he denies the ability of women to preach, in an essay where he uses that verb almost interchangeably with “prophesy,” “evangelize,” and “proclaim.” Instead, it’s his pragmatic response to the cultural context of North America: “If mission houses or churches are for the time being closed to them,” women would be led to other places.

Places like Kingsburg County, South Dakota. In Olson’s collection, a male pastor named N.C. Carlson recalled a revival there just before the turn of the century, led by Hilma Sivrin and Mary Madsen:

Places like Kingsburg County, South Dakota. In Olson’s collection, a male pastor named N.C. Carlson recalled a revival there just before the turn of the century, led by Hilma Sivrin and Mary Madsen:

…One of the woman evangelists had a good voice and much courage. She also played the guitar very well and when she strummed the strings the people were greatly moved. The other woman did the preaching. Many remember these sisters because of the message they brought that Jesus died for sinners. This is the only message that can redeem big and small, the mighty and the lowly.

Rev. Carlson decided “it was unimportant whether God uses a man or a woman… just as long as people do not die in their sins.”

“Souls were saved wherever these firebrand preachers journeyed or dwelt,” reported Josephine Princell’s biographer, Anna Lindgren. “They were men and women of a great, simple faith, who knew their God and expected Him to work.” Men and women. Indeed, some Swedish Free churches seemed to prefer women to men for such preaching, as their golden jubilee history explained in 1934:

Women workers were in great demand for a few years. It seemed at the time that this mode of work would become permanent. One or more churches even called women as pastors. Other churches desired and called none but women to conduct revival meetings and mission meetings. None but women were thought of or welcomed.

But then the author reports that the “none but women” movement “disappeared after a few years. It went as it came, with surprising suddenness.” It wasn’t until 1988 that the EFCA formalized its stance against ordaining women for pastoral ministry, but clearly E Free attitudes were changing even earlier in the 20th century.

What happened? “No simplistic answers will do,” warns Janette Hassey. The current policy has its own antecedents in Free Church history, after all. But as obviously, she concludes, “opposition to women’s ordination in the EFCA is not at all in keeping with at least [the Princell-Franson] segment of the historical tradition.”

The 1934 history suggests that E Free women ceased to preach and evangelize not so much because his spiritual heirs rethought Franson’s exegesis as because they inherited his pragmatism: “…[evangelism by women] served its purpose. Many souls were brought to Christ through the movement; and scattered groups of Christians here and there were greatly strengthened. It seems to have been one of God’s emergency methods for that day. As such it had its place and its value.”

Historian Timothy Larsen has suggested that 20th century evangelicals’ shifts on the issue of women in ministry often had more to do with respectability than theological revision: “Many longed for the evangelical Christian ministry to be seen as just as much a respectable profession as the mainline ministry, and women were deemed to undercut this professional image.” That fits with the notion that the work of women like Josephine Princell, Christina Carlson, Ellen Modin, Hilma Sivrin, and Mary Madsen was “one of God’s emergency methods for that day.” Hassey also emphasizes the professionalization of the E Free movement: “In the shift from mission societies led by the laity to organized churches with full-time salaried pastors, men consequently could enter a more secure ministry position and also support a family. Women in such a setting more likely served a local church as a parish visitor rather than as pastor.”

Historian Timothy Larsen has suggested that 20th century evangelicals’ shifts on the issue of women in ministry often had more to do with respectability than theological revision: “Many longed for the evangelical Christian ministry to be seen as just as much a respectable profession as the mainline ministry, and women were deemed to undercut this professional image.” That fits with the notion that the work of women like Josephine Princell, Christina Carlson, Ellen Modin, Hilma Sivrin, and Mary Madsen was “one of God’s emergency methods for that day.” Hassey also emphasizes the professionalization of the E Free movement: “In the shift from mission societies led by the laity to organized churches with full-time salaried pastors, men consequently could enter a more secure ministry position and also support a family. Women in such a setting more likely served a local church as a parish visitor rather than as pastor.”

And that’s a shame. Not only does the evangelical marginalization of women depend on the kind of exegesis that Franson warned against, but it shows how evangelicals risk losing what Don Dayton called the “certain innovative and experimental thrust to Evangelicalism that found expression” in practices that broke with convention, tradition, and authority and thereby brought the Evangel to new places and populations. Such innovation didn’t come easily to evangelicals. But “[a]fter passing through the trauma of breaking into such new practices” as the “field preaching” of George Whitefield and the hymn writing of the Wesley brothers, “Evangelicals were able to look back and see that their resistance had been cultural conditioning rather than some absolute understanding derived from the core of biblical faith.”

Likewise, Dayton concludes, “Evangelicals began to experiment with new roles for women in the church.” Time will tell if their dual commitments to biblical inspiration and evangelistic improvisation will lead more evangelicals to experiment again with roles for women that are both old and new.