“A little Puritanism would help us all.”

This striking recommendation comes from Commonweal magazine’s Paul Baumann, in a review of a new book by Daniel Rodgers, emeritus Professor at Princeton. The Puritans, those stiff characters oft reviled or parodied, are ever being pulled out of mothballs for some civic purpose or uplift. In a few weeks we’ll have the obligatory annual attention paid to Mayflower and pilgrim hat. Persons-on-the-street and students in U.S. classrooms may be forgiven for wondering why these people keep showing up in narratives about Who We Are as Americans, when they might rather forget them. The builders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony from the 1630s are, as historical actors, are easy to make unlovable.

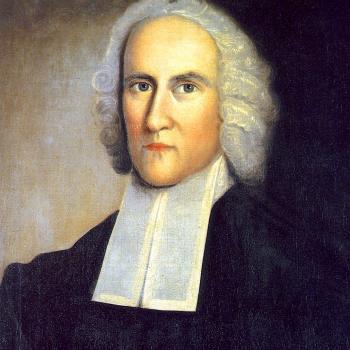

But that’s not what Rodgers is after. Rodgers’s As a City on a Hill excavates the meaning of “America’s most famous lay sermon” from Massachusetts Bay governor John Winthrop in the early seventeenth century, as he and others readied to settle a colony. The way this address, sometimes called “A Model of Christian Charity” or the “Arbella sermon,” commonly has been understood stands in contrast to what it actually says. Rodgers traces how subsequent Americans, perhaps most prominently Ronald Reagan, have claimed its words to say something about what America means. Reagan’s late cold-war likening of the United States to a “shining city on a hill” assumed for us a vision of freedom and goodness. Rising again to morning in America, Reagan positioned the United States as on the right side of history and of the angels, come to prominence in order to shine forth good example.

But, as Rodgers points out, Winthrop did not exactly say that. This book tells the story of a text so well known “we barely know it at all.” Winthrop’s actual words, in Rodgers’s words, were turned from text to origin story to “invented foundation for the new world colossus that the United States had become.”

Winthrop says some things that Americans, egalitarians, must find hard to swallow. The sermon comes out defending hierarchy, inequality, the natural kind. Things are as they should be when some are high and others are low. It is providence. Inequality exists, among other reasons, so that “every man might have need of the others” and that “they might be all knit more nearly together in the bonds of brotherly affection.” We are different in order that we might help each other and draw near in love. It is a beautiful text, challenging in the way something from another time and another cast of mind should be, but provocative.

Misunderstanding of the document might come from reading only the famous parts, as I have noticed with students. Assuming full understanding from the first few sentences of the Declaration of Independence or the preamble to the Constitution is like guessing what Winthrop means by “city on a hill” from just that section. Most of the sermon plods along distinguishing rules of justice and mercy in quotidian economic contexts, when to lend, when collect a debt and when to forgive it.

So why might we all need a little more Puritanism?

How about love? This is what Winthrop tells fellow settlers that they owe each other:

“Love is the bond of perfection….There is no body but consists of parts and that which knits these parts together, gives the body its perfection, because it makes each part so contiguous to others as thereby they do mutually participate with each other, both in strength and infirmity, in pleasure and pain….[We must] love brotherly without dissimulation, we must love one another with a pure heart fervently.”

He tells his fellows to be united, to be “knit together in this work, as one man.” He acknowledges that all suffer if one is let to suffer without help. People must “partake of each other’s strength and infirmity; joy and sorrow, weal and woe….We must bear one another’s burdens. We must not look only on our own things, but also the things of our brethren.”

To be sure, Winthrop and colleagues spoke in an idiom Americans no longer own, and perhaps should not borrow, that God would reward or punish according to their corporate faithfulness in keeping the covenant. But here’s the rub. In spite of the frequent misreading of this as a boast, that God would bless the socks off of Massachusetts and make it conspicuous, Winthrop stresses the warning much more. Winthrop cautions of punishment to be brought on Massachusetts if they blew it. Living in justice and mercy is hard.

There was only one way to “avoid this shipwreck,” in Winthrop’s words: “We must delight in each other; make others’ conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body.” Doing that would encourage discovery that God would “command a blessing upon us in all our ways.” Massachusetts could be made an example, not of a free and blessed people, but of what happens to a people who choose selfishness over love.

“For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world….[causing prayers] to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going.”

The Puritanism we might need more of includes some points Winthrop makes:

That diversity exists to draw us together in need and for common good.

That individuals differ significantly but our corporate identity matters very much.

That we are in this together for a high purpose.

That giving in to selfishness is may wreck the whole thing.