Nearly forty years ago, a minister, a rabbi, and two priests went to the White House, and together with the President and other religious leaders, they planned a special series of Thanksgiving observances. Their Thanksgiving events, however, did not feature turkey feasts and English Pilgrims. Rather, the Thanksgiving they planned called for fasting and church fundraisers to collect money to aid Southeast Asian refugees.

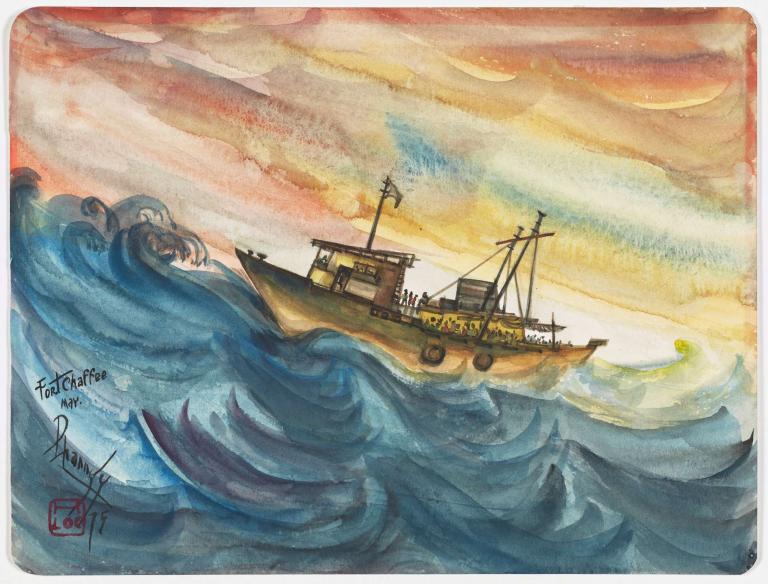

The year was 1979, and a humanitarian crisis was unfolding in Asia. “Boat people” were escaping Vietnam in droves, while Hmong and Lao refugees were fleeing the Pathet Lao. In neighboring Cambodia, Pol Pot had fallen from power that year, after killing a fifth of the Cambodian population, and those who had managed to survive were starving and seeking refuge in Thailand.

After a day of meetings, the religious leaders held a press conference with President Jimmy Carter. After announcing his plans to increase government spending on refugee relief and resettlement, President Carter urged religious communities across America to “match the government effort” and give generously to refugee aid groups. “I ask specifically that every Saturday and Sunday in the month of November, up until Thanksgiving, be set aside as days for Americans in their synagogues and churches, and otherwise, to give generously to help alleviate this suffering,” he said.

Religious leaders reiterated his call. Rabbi Bernard Mandelbaum proposed a Thanksgiving dinner where Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish people would gather to eat “what a typical Cambodian eats on a day when he’s starving.” His suggestion for an interfaith Thanksgiving feast where people would eat close to nothing was perhaps made in jest. Nonetheless, Rabbi Mandelbaum was deeply serious about the shared conviction of the government and religious leaders who had gathered that day at the White House. “I think it’s good for America that all of us stand together in this prime response of religion which is ‘Love your neighbor as yourself,’” he said.

Refugee politics in 1979

The Thanksgiving events proposed by President Carter and the minister, the rabbi, and the priests may today seem quaint, but the pro-refugee advocacy of these religious and government leaders was in fact quite bold and rather unpopular in 1979. Then and throughout the twentieth century, Americans widely opposed admitting refugees for resettlement. One national Gallup poll conducted in May 1975, just one month after the fall of Saigon, found that only 36 per cent of Americans surveyed favored the resettlement of Southeast Asian refugees; 54 per cent of Americans surveyed opposed it. Attitudes toward Southeast Asian refugees warmed somewhat over time, but American reluctance to admit Southeast Asian refugees remained consistent throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Even a full decade after the end of the Vietnam War, a plurality of Americans believed that the United States had accepted too many refugees.

Despite the opposition, nearly a million Southeast Asian refugees were resettled in the United States, and their arrival sometimes provoked hostile and even violent reactions. A New York Times profile of Niceville, Florida, reveal the scope and intensity of anti-refugee sentiment. A community located near Eglin Air Force Base, one of the four military-run camps that housed newly arrived Vietnamese refugees, Niceville was not, despite its name, particularly nice to the Vietnamese newcomers. When the local radio station polled area residents about the 1,500 Vietnamese being airlifted from Saigon, 80 per cent of the people said that they did not want the military to bring refugees to their town. At one point, residents circulated a petition demanding that refugees be sent to a different place, and school children reportedly made jokes about shooting refugees.

The reasons for opposing refugee resettlement varied and included concerns about the potential impact on local employment, the strain on government resources, the threat to national security, and the possibility of Communist infiltration. The belief that Southeast Asian refugees were dirty and unable to assimilate also motivated anti-refugee sentiment. “There’s no telling what kind of diseases they’ll be bringing with them,” said Vincent Davis of Niceville. (When asked by the reporter to identify which diseases the Vietnamese refugees carried, Davis replied, “I don’t know,” but then added that “there’s bound to be some of those tropical germs floating around.”) Sometimes the opposition was due simply to anti-Asian racism. At Fort Walton Beach High School, near Niceville, students even discussed plans to establish a “gook klux klan.”

Refugee politics in 2018

As this recent history shows, the nativism of 2018, while ugly, has a long and deep-rooted history. Today as in 1979, Americans remain skeptical of refugees and asylum-seekers. The Pew Research Center found this spring that, overall, about half of Americans (51%) believe that the United States has a responsibility to accept refugees. However, opinions divided on partisan lines; only 26% of Republicans believe that the United States should be responsible for resettling refugees. Public opinion about the people in the “migrant caravan,” many of whom are fleeing violence in Central America and hope to seek asylum in the United States, are also negative. One recent poll found that 42% of polled voters believe that Mexico should return the people in the migrant caravan back to their home countries.

Of course, the situation today is also quite different from that of 1979. Most obviously, President Trump is no President Carter, and the Trump administration has actively chosen not to lead the world in showing a generous response to refugees. In September, for example, President Trump slashed refugee admissions to 30,000 a year, the lowest number since the creation of the modern refugee resettlement system in 1980. In addition, just last week, he announced plans to make it more difficult for people to claim asylum; according to Sabrina Ardalan of the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, these policy changes will make claiming asylum nearly impossible. To be sure, as Michael Barnett argues, the Trump administration’s stance on refugees, while more restrictive than previous administrations, is not exceptional compared to other nations, which, as a general rule, treat refugees quite badly. However, what sets President Trump apart is his harsh rhetoric. While previous American presidents have at least gestured toward the lofty ideal of the United States as a refuge for the persecuted, the downtrodden, and the freedom-loving, President Trump has repeatedly demonized refugees, asylum-seekers, and immigrants as dangerous criminals and terrorists who pose a dangerous threat to America.

The opposition to refugees and asylum-seekers has not been limited to President Trump. Other politicians have mobilized voters through the crass exploitation of nativist fear and hate. Anti-immigrant, neo-Nazi, and anti-Muslim hate groups have been on the rise, and this week, the FBI released a report that found that in 2017, hate crimes—of which almost 60% were motivated by race, ethnicity, or ancestry—increased by 17%. Last month, the belief that refugees are “invaders that kill our people” even compelled Robert Bowers to gun down 11 worshipers at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue, which he targeted in part because he linked it to the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), a voluntary agency that resettles refugees. (As Jaclyn Granick and Britt Tevis point out, “Anti-Semitism, nativism and anti-immigrant sentiments have long been inextricably intertwined.”)

“We are called by our faith traditions to welcome the stranger”

If government leaders are pulling back their commitment to refugees and asylum-seekers, how are people of faith responding? In the run-up to the midterm election, some news coverage suggested that white evangelical women, horrified by the separation of families at the border and the ban on Muslim refugees, were abandoning the Republican party and backing Democratic candidates such as Beto O’Rourke. However, a look at the voting patterns in the midterm elections last week indicates that most white evangelical Christians remain solidly supportive of the Republican party and, by implication, its harsh restrictionist stance on refugees and immigrants.

Still, many religious groups insist that the United States should continue to welcome refugees, asylum-seekers, and immigrants and have expressed this commitment through advocacy and daring acts of protest. Leaders of faith-based voluntary agencies such as World Relief, Church World Service, and the United States Conferences on Catholic Bishops Migration and Refugee Services have repeatedly condemned the reduction of refugee admissions and the treatment of asylum-seekers. Religious leaders have also been organizing their own caravans, willingly putting their bodies in danger in order to protest government policies and show compassion to migrants. For example, rabbis from across the country are undertaking a “pilgrimage” to the southern border. This “sacred journey,” Rabbi Miriam Terlinchamp explains, arises from Jewish commitments to “decency, justice, and compassion” and aims “to stop the unacceptable practice of imprisoning immigrant minors, and ensure protection for those seeking refuge within our borders.” Similarly, the New Sanctuary Coalition is forming a “sanctuary caravan” led by two dozen faith leaders who hope “to prevent vigilante justice” and aid migrant families. “Exodus is not new,” says Pr. Eduardo Fabian Arias. “We are called by our faith traditions to welcome the stranger. We will answer that call.” One humanitarian activist, Scott Warren, who was recently arrested and charged with federal criminal counts of harboring illegal migrants in the Arizona desert, has even argued that because his religious convictions require him to aid immigrants, his actions are protected by the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Religious groups doing refugee resettlement work have also benefited from generous giving. Donors on Facebook contributed over a quarter million dollars to HIAS within the first three days after the Tree of Life massacre, and religious congregations are donating money, time, and talent to resettlement efforts, even when there are no refugees to help—yet. In Tarrant County, one of the counties that resettles the most number of refugees in Texas, the Trump administration’s policies have caused the number of refugee arrivals to decline 71.7%. Churches in Tarrant County that were busily preparing homes, meals, medical care, employment, and English classes for newly arrived refugees found that the families they eagerly hoped to assist never arrived. Nevertheless, the churches have continued to give, prepare, and hope. Shalaina Abioye of Catholic Charities Fort Worth observes that, though “the numbers are lower,” Tarrant County has not lost its “spirit of welcoming refugees.”

“Thanks, God, for the saving of life”

Like the minister, rabbi, and priests who visited the White House to plan Thanksgiving in 1979, people of faith today are leading the effort to press for government policies that are generous and compassionate to refugees, asylum-seekers, and immigrants. These religious activists face formidable opposition. As was the case four decades ago, they must contend with a general population that is wary of refugees and other migrants. Now, however, they must also deal with a government that is no longer a willing partner, but a hostile adversary. In an era when the U.S. government is choosing to turn its back on the world’s most vulnerable people, it is clear that the moral leadership of people of faith matters more than ever. And why precisely does their matter? Because the lives of refugees fleeing violence and persecution are severely at risk.

Another Thanksgiving story offers a powerful reminder of why the work of refugee advocacy is so important. In 1991, the Hmong Christian Church of God in Minneapolis gathered for the fifteenth annual “Thanksgiving service.” The event was not actually in November, but in May, and the intent was not to commemorate the migration of English Pilgrims who sailed to Massachusetts on the Mayflower, but the migration of Hmong refugees who flew to the United States on an airplane. The program cover for the “great memorial celebration” in fact featured a drawing of an oversized jetliner, superimposed on the outline of the globe. The airplane appeared to be leaving Southeast Asia, represented by a Hmong man holding a Laotian flag, and careening toward the continental United States, where another Hmong man bearing an American flag offered the greeting, “welcome to the U.S.” Projecting from the top of the globe was a large crucifix, under which read the joyful declaration, “Thanks God for the saving of life.”

On the inside of the program, the church’s pastor, Rev. Young Tao, lists the reasons for which the congregation had gathered to “celebrate this thanksgiving”: among them, “to Honors the Government of the United States, the Governor of Minnesota and all those in authority under him, and the kind citizens of Minnesota who throug their gracious generosity have assisted us to a happily resettle here in this wonderful State” and “to Show our gratitude and honor to the agencies, Churches, sponsors, and friends who have shared willingly with us and have provided us with the necessities of the life such as food, clothing, furnitures, and housing.” Later, the pastor emphasizes that the Hmong people should thank God above all. “But God pours out His love, and the United States government has fill with all of loves,” the pastor writes. “And by the Churches, agencies, and friends, They accept the Hmong into their home land. This is our thanksgiving and gratitude to continually.”

As this Thanksgiving service reveals, the members of the Hmong Christian Church of God were profoundly grateful to find a new home in the United States. The misery they had endured throughout their refugee journey from Laos, and the resilience and thanksgiving they displayed in the years after, offer a compelling lesson for all Americans—that living, breathing, celebrating, long-suffering human beings are at the center of the refugee policies that politicians so cruelly deploy as a political weapon. It is these human beings who are the very reason why people of faith are rejecting the actions of the current government and pressing for refugee policies that show “gracious generosity” and make possible “the saving of life.”