Today Peter Choi, author of the new book George Whitefield: Evangelist for God and Empire joins us at the Anxious Bench. Historians, journalists, and pundits debating the nature of contemporary evangelicalism often set the politicization of recent evangelicalism against an idealized historical evangelicalism. With his history of Whitefield and eighteenth-century evangelicalism, Choi complicates that narrative in ways that help reframe our contemporary conversations.

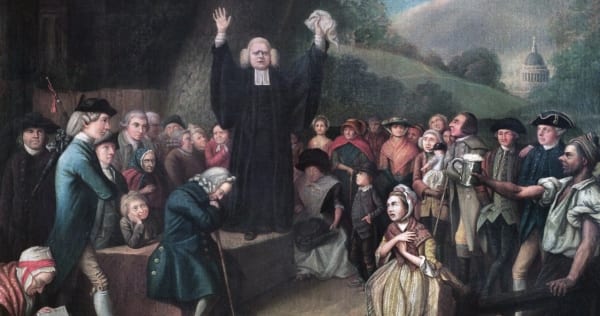

For many evangelicals, George Whitefield (1714-1770) represents the very best of their tradition. He remains one of the few unifying figures in a fissiparous movement. At the risk of overstating things, the Grand Itinerant may serve as a basis for definition: “An evangelical is someone who likes George Whitefield” at least sounds plausible. Even historians who today question the possibility of finding such a thing as evangelicalism in the eighteenth century use labels like “Whitefieldarians” to describe a nascent religious movement that later became evangelicalism.

It’s worth remembering, however, that in the eyes of many contemporaries, the honey-tongued preacher represented the very worst of religion in their day. Critics assailed him as rancorous and divisive, and even many friends considered him a liability.

George Whitefield: Evangelist for God and Empire seeks to avoid the extreme reactions this preacher so often evokes, whether adulation or derision. Toward that end, the book makes space for sincere religious motivations but also does not shy away from a closer look at his more “worldly” activities. To offer a few examples:

- Whitefield was not only the most famous preacher in the English-speaking world but also a leading exporter of British imperial culture to America.

- He persisted many years as the most unrelenting agitator for the legalization of slavery in Georgia, exclaiming “Thanks be to God!” when his day of legislative victory finally came.

- He used racial categories in a hierarchical manner, to denigrate Native Americans and Africans and privilege Europeans, especially British subjects.

- Long after he stopped publishing his spiritual writings, Whitefield penned war propaganda with loud denunciations, bordering on demonization, of non-British and non-Protestant enemies: the French, the Spanish, the Catholics, etc.

The cult of celebrity surrounding Whitefield has largely shielded him from scrutiny over these matters. But reckoning with the dark, unspiritual side of early evangelicalism is a necessary step for understanding later developments.

The cult of celebrity surrounding Whitefield has largely shielded him from scrutiny over these matters. But reckoning with the dark, unspiritual side of early evangelicalism is a necessary step for understanding later developments.

To be sure, there were other influential leaders who may help to build a more positive impression of early evangelicalism. But few had the reach and influence that Whitefield did, nor were their views as representative. The Salzburgers in Georgia opposed slavery as did John Wesley in England. Quakers like John Woolman and Anthony Benezet, early abolitionist leaders in America, deserve mention as well. Nevertheless, they all did their work in the shadow of a colonialist, racialized framework that elevated whiteness and Protestantism, creating what Willie James Jennings has called “a diseased social imagination.” As Rebecca Goetz has shown, ideas like “hereditary heathenism” gave theological weight to emerging ideas of race. And a doctrine of “Protestant supremacy” constructed in the colonial period to justify “Christian slavery,” according to Katharine Gerbner, pre-dated and invigorated later developments like white supremacy. David Hempton’s phrase “European civilizational chauvinism” can provide a helpful entry point for understanding familiar evangelical leaders like George Whitefield in the new light of these studies.

What we may then see is that despite valiant on-the-ground efforts, early abolitionists buckled under the weight of pragmatic and ideological challenges. The Salzburgers who cited fears of interracial marriage and slave insurrection as key reasons against slavery could not stop the force that was Whitefield on a crusade to acquire slaves for his plantation in Georgia. And many decades later Wesley’s deputies in America, Francis Asbury and Thomas Coke, accommodated the idealism of their mentor to the intractability of the slave economy. Even in British abolitionist efforts against the slave trade, where Wesley’s influence had a greater effect, works by David Brion Davis and Christopher Brown have tempered narratives that center heroic humanitarian motivations.

By destabilizing the myth of greatness that has long surrounded the founding era of evangelicalism, my book offers an exercise in ground clearing. It creates the space to see that rather than a mature and monolithic European faith passed on, mostly intact, to Native American and African recipients, early evangelicalism represented the shared faith of people from diverse parts of a world in tumult, with various embryonic stages, held from a variety of cultural positions, and highly contested throughout a long formative process. Evangelicalism resists easy definition today because from the beginning its fractious community contained multitudes.

Evangelicals of color especially can provide an illuminating foil to the mostly white male figures who have dominated our imagination. Phillis Wheatley and Olaudah Equiano are two prime examples of converts to Christian faith who became formidable evangelical actors in their own right. Their conversion arose out of, and further catalyzed, their efforts to negotiate the terms of their enslavement. Their religion was not a European faith, moreover, for they practiced a Christianity often differentiated from what they saw in their white counterparts.

Wheatley wielded the poet’s pen as a subtle and masterful writer of verse. Though some interpreters have criticized her appearance of comity and compliance, a careful reading of her writings reveals a resolute spirit unafraid to challenge her enslavers. As one biographer, Vincent Carretta, put it, “We have increasingly come to appreciate Wheatley as a manipulator of words; perhaps we should have more respect for her as a manipulator of people as well.”

It is a telling example of Wheatley’s subtle artistry that the poem most responsible for her transatlantic fame, her elegy to George Whitefield, took exception to the preacher’s paternalistic attitude toward enslaved Africans. Carretta observed: “Her elegy effectively rejects Whitefield’s endorsement of passive acceptance of slavery by the enslaved.” In addition, she went “far beyond Whitefield in imagining the capaciousness of an American community.” While praising the Grand Itinerant, she resisted his bifurcation of races, asserting a broader American identity that included Europeans and Africans.

A further example can be found in a private letter to Samson Occom, in which Wheatley displayed biting sarcasm, pulling no punches in her critique of the American colonists’ cry for freedom against the British: “How well the Cry for Liberty, and the reverse Disposition for the Exercise of oppressive Power over others agree,––I humbly think it does not require the Penetration of a Philosopher to determine.” Her remark predated Samuel Johnson’s more famous quip, which came a year later: “How is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of the Negroes?” Elsewhere, Wheatley went as far as to compare American slave owners to “Modern Egyptians.”

Long before W. E. B. Du Bois described the “double consciousness” of African Americans navigating their way through white society, Wheatley was adept at cultivating a presentable public image while harboring a much more critical, we could say cynical, outlook underneath the surface.

Equiano was perhaps the most successful Christian convert of African descent in the eighteenth century. An astute publicist as well as a gifted writer, Equiano embraced his double identity as “The African” as well as Gustavus Vassa, the name given by one of his owners. He sought to raise the profile of Africa in public opinion, frequently pointing out shared characteristics between Hebrews and Africans in his reading of the Old Testament. His was a powerful voice of black Atlantic Christian protest, issuing strident denunciations of white evangelical hypocrisy: “O ye nominal Christians! Might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God?”

A bestselling author, Equiano possessed the marketing genius of George Whitefield and the political savvy of Benjamin Franklin. He crisscrossed the Atlantic world promoting his book, which had an unusual frontispiece of Equiano gazing directly at the reader. Among the picture’s other notable features, his thumb rests on Acts 4, indicating not only his ability to read the Bible on his own but also with authority to teach others. Commentators have focused on verse 12: “Neither is there salvation in any other” (KJV). Yet the broader context of chapter 4 may be even more significant for Equiano’s subversive purposes, for it is a text in which Christian converts challenge the authority of a religious establishment that has lost its way. That story of Peter and John against the Sanhedrin became paradigmatic for Equiano, who appears to have used the apostles’ insubordination as a model for his own restive life. Indeed, he took his conversion to Christianity as authorization to challenge the sins of British Protestantism.

* * *

Evangelical religion arose in the era of empire and diaspora. It was a time when transatlantic migration and border-crossing encounters served to upend settled views of the world, disrupting inherited theological convictions and setting new directions. Creative spiritual leaders like Whitefield used innovative methods to advance Christianity. He also contributed to the imperial agenda and to a process of theological racialization, which harmed Native Americans and Africans.

But as converts to Christian faith, evangelicals of color also laid claim to their membership in the one body of Christ. Leading figures like Wheatley, Equiano, and many others bemoaned the cultural chauvinism of their European coreligionists. They challenged the racial sins of white evangelicalism in their day.

A sober reassessment of Whitefield can give us eyes to see and ears to hear not only the failures of early evangelicalism, but an alternative message put forth by early evangelicals of color. It is a vision that has endured, with unevenness but also gathering force, throughout the long history of evangelical Christianity in America.