In the upper Midwest, Lent is not simply a season for fasting—it’s a season for fish fries. While they’re supposed to be solemn days of self-denial and sacrifice, Lenten Fridays have provided the opportunity for people to gather together for festive events that offer a delicious diversion from the dreariness of the late winter months. In many cities, local newspapers publish the times and places of all the fish fries in the area, and beginning at mid-afternoon, an ambitious (devout?) Catholic could do a circuit of all the fish fries hosted at churches, schools, American Legion Posts, Knights of Columbus Halls, and Moose Lodges, so long as she is armed with a good pair of elastic-waist-banded pants and a robust appetite for perch, walleye, hush puppies, tater tots, French fries, coleslaw, green bean casserole, and salad (with ranch dressing, of course—#Midwest). The food served at a good fish fry is so divine that, as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel declared, it “will make you forget whatever you’re giving up for Lent.”

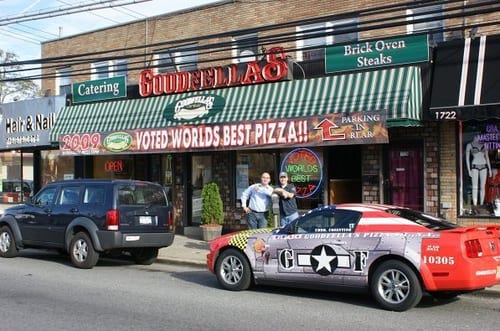

Friday fish fries were such a fixture of my childhood that it never occurred to me that there could be any other way to observe Lent until I moved to New York City and began teaching at the College of Staten Island. My first year, when I was teaching a seminar about religion and immigration, I casually asked my students, many of whom were Italian American Catholics, where I could find the best Lenten fish fries on the island. My question literally caused them to laugh out loud. “Professor, we don’t eat fried fish on Fridays during Lent,” they said. “We eat cheese pizza!” They weren’t joking. Observing Lent by eating cheese pizza is such an important local tradition that the borough newspaper, the Staten Island Advance, recently ran a story featuring several popular pizzerias that area Catholics frequent during Lent. “It’s a lot more busy on Friday nights during the Lenten season, the volume really picks up,” George Mallon explained to the Advance. Mallon, the manager of Denino’s Pizzeria and Tavern in Port Richmond, noted that his restaurant sees twenty percent more people on Lenten Fridays, and they do brisk business selling cheese pizza with vegetarian toppings. The Ursini family, for example, enjoyed their cheese pizza with peppers and onions, and they told the Advance about their family’s 15-year tradition of observing Lent at Lee’s Tavern in Dongan Hills, another Staten Island pizzeria. Paul Ursini confessed that it was “hard going without the sausage.” However, he emphasized that abstaining from meat was an important practice. “We celebrate religion and have to follow the guidelines,” he said.

Like Paul Ursini, the Italian American Catholic students in my seminar at the College of Staten Island took the matter of celebrating religion and following the guidelines of their faith very seriously. For this reason, they were shocked by a National Public Radio story that I shared with them about how Catholics in other regions of the United States observe Lenten Fridays by eating muskrats, which live in the water and are therefore considered by some people to be seafood. While my students found my description of church fish fries to be quaint and “weird,” they considered muskrat feasts to be “wrong.” “Muskrat is meat!” they insisted. “Those Catholics are cheating!” To be sure, official statements from church officials indicate that they agree with my students that muskrat is, indeed, a type of meat. At the same time, though, Catholic leaders have been somewhat accommodating of the local custom—or at least they have a sense of humor about it. In southeastern Michigan, where eating muskrat is a tradition, the local lore is that a nineteenth century bishop offered a special dispensation to area Catholics to eat muskrat on Lenten Fridays. And according to a March 2006 article in the Wall Street Journal, one bishop, when asked about whether it was acceptable to eat muskrat during Lent, responded that anybody who ate the rodent for supper was “doing penance worthy of the greatest saints.”

What has most intrigued me about discussions of Lenten food traditions is not simply the revelation that there are a wide variety of interpretations, practices, and customs—it’s that these differences provoke such strong feelings. That my students used the word “cheating” to describe the tradition of eating muskrat is particularly curious to me. Cheating involves breaking rules and acting dishonestly in order to achieve something desirable. In truth, my students conveyed no desire to eat muskrat. Quite the opposite: they expressed revulsion at the idea, and they didn’t actually feel that their strict interpretation of the rules cheated them out of a muskrat meal because they didn’t want a muskrat meal in the first place.

I think that something else is at stake in the debate about eating muskrat during Lent, both for the practitioners and the critics of this tradition, and it’s not really about what gets to count as meat. More fundamentally, this Lenten Friday food custom reveals the uncomfortable truth that while the Catholic Church is renowned for its rules, religious practices vary considerably on the ground, and people make different choices about how to interpret and adhere to their religious obligations. Concern about “Cafeteria Catholics,” it turns out, can touch on issues beyond abortion and birth control—it can cause controversy over choices made in a literal cafeteria.

The unease about eating muskrat during Lent also centers on matters of community and belonging. Lenten muskrat dinners are proud, public rituals that offer a communal expression of a distinctive ethnic and regional culture. At the same time, this practice—and its people—have disturbed middle-class Catholics, who take pride in their respectable religiosity. Eating muskrat, in their view, is simply not good taste. Ultimately, the debate about Lenten muskrat dinners is about more than what Catholics eat on Friday night—it’s about ethnic and religious identity and the politics of proclaiming it, policing it, and presenting it to the consuming public.

“The Muskrat Frenchman”

The Lenten custom of eating muskrat is well established in my home state of Michigan. Although the practice is commonly associated with “downriver” communities such as Wyandotte, friends and family recall encountering muskrat feasts as far south as Monroe and as far north as Bay City. The custom is popular enough that demand in Michigan outweighs supply. National Public Radio reports that Michiganders’ appetite for muskrat has diminished the local muskrat population to the point that muskrats are now brought in from Ohio.

Many Michiganders remain unfamiliar with this Lenten tradition, though, and perhaps this should not come as a surprise. In addition to being a controversial interpretation of church rules on fasting and abstinence, eating muskrat during Lent is a tradition associated with a long-overlooked cultural group known as the “Muskrat French,” also called the Mushrat French, which are a community of French Canadians who have lived in the vicinity of the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair since the eighteenth century. In his 2014 article in The Michigan Historical Review, James LaForest traces the history of Muskrat French people and their distinctive regional culture.

He argues that, beginning in the eighteenth century, the British and Americans in the region were suspicious of the Muskrat French, in part because they had close “cultural and familial ties with the Indians.” By the nineteenth century, these Detroit River French communities continued to be seen as “inferior and untrustworthy,” and newsmedia depicted the group as “an exotic, marsh-dwelling tribe whose language was unintelligible both in English or French.” LaForest shares this description of Detroit River French Canadians from a New York Sun article published in 1899:

The muskrat Frenchman is to be found dwelling in the flats along the Detroit River. In stature he is small, in complexion like to his native mud, in habits simple and uncleanly, in appetite satisfying himself with roast ‘muskrat shtuff wix onyan,’ washed down with whiskey little better than raw alcohol. In imagination he is wild, vivid, fanciful, extravagant.

The Sun article continues on to describe a scene in which a Muskrat Frenchman played cards in a saloon in the company of “unkempt, unwashed” fellow Frenchmen. According to LaForest, these negative depictions persisted through the 1920s.

Perceptions of this community began to change in early twentieth century, however, when Detroit River French Canadians made efforts to claim and celebrate their cultural identity. Muskrat feasts played a particularly important part in these public displays of cultural heritage. LaForest writes,

At a 1906 carnival sponsored by the Monroe Yacht Club, muskrat was served and proved to be popular with the local population. Public muskrat dinners were held throughout the following century to great fanfare. They became events that attracted ‘Old Frenchmen’ from throughout the Midwest, who journeyed to take part in cultural celebrations. Some of the festivities included up to 4000 guests, ‘high-class barkeepers of Detroit,’ and a vaudeville show as entertainment.

Today’s Lenten muskrat dinners must thus be seen in this historical context, as a positive performance of both ethnic and religious identity and as an expression of cultural pride by the French Canadian people of the Detroit River region.

“Nuclear power does not rile these people up. Muskrats do.”

Over the course of the twentieth century, muskrat dinners became popular community events that were associated with an improvement in the status of the Muskrat French. Nonetheless, these muskrat feasts, especially when conducted on Friday during Lent, would eventual provoke controversy.

In the late 1980s, southeast Michigan’s Lenten muskrat tradition captured national attention when Michigan public health officials attempted to restrict the sale of muskrat meat only to state-approved and inspected sources. State health officials justified the proposed measure as a matter of public safety, but the absence of inspection procedures or approved sources meant that the rules could effectively amount to a ban. The public protested vigorously in response. “I’ve never seen so many people upset about an issue,” said State Representative Jerry Bartnick to the New York Times. “We had almost 500 people at the courthouse for hearings on muskrat legislation.” Dennis Au of the Monroe County Historical Museum noted that, in contrast, only a few people showed up to protest a nuclear electric station. “Nuclear power does not rile these people up,” Au said. “Muskrats do.”

In a victory for the pro-muskrat crowd, the state health officials eventually backed down, and the proud local tradition of eating muskrat, so deeply tied to the cultural identities of the Muskrat French and the southeast Michigan region, ultimately prevailed. One restaurant owner, John Kolakowski, expressed relief at the decision and excitement about the continuation of his booming business. “On a normal Friday we’ll do about 80 muskrat meals,” Kolakowski said to the Times. “I’m gearing up to serve 180 on Good Friday.”

A few years later, though, another controversy about muskrat feasts arose in neighboring Wisconsin, and with a very different outcome. As the Milwaukee Sentinel reported in May 1993, the ACT, the standardized test used for college applications, included a reading comprehension passage about how Catholics in southeastern Michigan eat muskrat during Lent. The reading passage prompted Catholics in Wisconsin to write incensed letters to Governor Tommy Thompson, himself a devout Catholic. Responding to his constituents’ outcry, Thompson wrote an official letter to the President of American College Testing, Richard Ferguson, in which he complained about what he considered to be an offensive misrepresentation of Catholic beliefs. Catholics understand that muskrats are forbidden to eat on Fridays during Lent, Thompson insisted, because Catholics know that muskrats are not fish. Furthermore, Thompson argued that the reading passage was harmful because it could undermine the Catholic faith of impressionable teenagers. “The passage may also cause some young Catholics to question the validity of tenets of their own faith,” he wrote. “This is especially likely when these erroneous ideas are encountered under conditions where time is short, test takers are not able to study the information carefully, and there are no facts available to balance these unusual notions.” He urged the ACT to “improve the process of review for cultural sensitivity.”

Thompson’s efforts were, at first glance, an effort to ensure that Catholics adhere properly to church teachings and to prevent their backsliding into improper, non-Catholic practices. However, when interpreted in light of the broader history of Lenten muskrat traditions and their connection to the marginalized Muskrat French community, Thompson’s arguments reinforced the long-standing view of Detroit River French Canadians as wild, primitive, inferior people whose way of life pose a danger to true, civilized Catholics. Thompson was not only policing practices, but, indirectly, policing the boundaries of who gets to claim being a real Catholic.

Ultimately, a comparison of the controversies in Michigan and Wisconsin reveals how the identity politics of eating muskrat varied according to context. In Michigan, the Lenten tradition of eating muskrat is a proud expression of ethnic and regional identity, and when the muskrat custom was threatened, the people rose up to protect it and demanded that the state government withdraw its proposed regulations. In contrast, Catholics in Wisconsin saw the Lenten muskrat tradition as a threat to their faith and a stain on the public image of American Catholics, and as a result, they demanded that their state government prevent the ACT from including readings about it. Seeing themselves as the protectors of authentic Catholicism, Thompson and other Wisconsin Catholics sought to distance themselves from practices and people they considered less legitimate, less civilized, and less Catholic. These actions are perhaps not surprising. If the Muskrat French worried about preserving their identity, so, too, did Wisconsin Catholics worry about protecting their identity and social position as true, respectable Catholics.

Like the Christmas season, the weeks leading up to Easter are rich with food traditions for Catholics, especially for people whose religious identities are so intertwined with their ethnic and regional identities. There are fish fries in the church basements and cheese pies at the neighborhood pizzerias. There are sugar-sprinkled, jelly-filled Polish paczki for the days before Ash Wednesday. There are squishy, fluorescent Peeps that aren’t necessarily religious, or even food, but which are pretty to see in the drugstore aisles anyway. And there are Lenten feasts of muskrat, deep-fried or served in corn, and sometimes accompanied by beaver, another water mammal with debated status as Friday-friendly fare. The irony, of course, is that while Lent is supposed to be a holy period of prayer and penance when Christians are expected to abstain from food, food remains a central part of the traditions and practices of this season.

As multi-sensory emblems of identity, these food choices broadcast to the world who people are, what communities they belong to, and what values they hold. And when certain food customs—eating muskrat, for example—cross boundaries and cause controversy, the event speaks important truths about who people are, and who they want to be. There are rules, and there are real-life choices, and the distance between these two things are what makes religious life in America so rich and so complex.