“If you go to Europe looking for world war,” I wrote after my first time teaching a World War I travel course, “you’ll see crosses everywhere.” So as Good Friday nears and I prepare to lead a June tour on the two world wars, I find myself thinking again how the image and idea of the Crucifixion helped people to make meaning of history’s most devastating conflicts.

In his landmark book on The Great War and Modern Memory, the WWII veteran-turned-literary scholar Paul Fussell notes that crucifixion was one of the most “insistent visual realities” of the Western Front. Not only did British propaganda spread stories of a Canadian sergeant crucified by the Germans, but the standard field punishment for minor offenses — leaving a soldier tied to a wagon, spread eagled — inevitably came to be called “crucifixion.” Physical representations of Calvary appeared at countless crossroads (or “Crucifix Corners”) in France and “Crucified Belgium.” And, of course, in graveyards. In Ypres’ town cemetery, a German shell buried itself, unexploded, between a wooden cross and the figure of Christ. The dud, reported the British journalist/soldier Stephen Graham, became “an accidental symbol of the power of the Cross.”

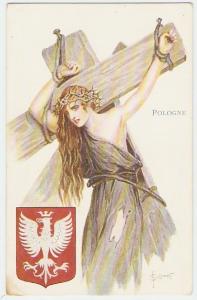

It was just one of many ways that those who fought and observed the Great War “readily embraced the image [of the Crucifixion] as quintessentially symbolic of their own suffering and ‘sacrifice.’” It wasn’t just Britons. As Philip points out in his book on WWI, Crucifixion analogies showed up in other countries’ responses to the “great and holy war.” A German preacher insisted that the Allies had treated his nation “[a]s Jesus was treated.” American propaganda posters regularly featured crucifixions — and “often depicted,” Philip adds, “attractive young female victims.” (See this 2014 post by Philip for more examples of how crucifixion was visualized during 1914-1918.)

Crucifixion took on more complex forms in postwar art. In his 1928 painting “Sacrifice”, Charles Sims turns the eyewitnesses to Christ’s death into mourning parents. (His own eldest son was killed in 1915.) William Roberts sketched a study of the battlefield in which the living soldiers are hoisted on crosses while the dead gamble for their garments. Whenever I see Charles Sargent Jagger’s relief “No Man’s Land” in the Tate Britain, the contorted body on the right reminds me of the terrifying crucifixion in Mathias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece.

As Fussell points out, war poets drew freely on the Crucifixion story. It helped them to convey the suffering of fellow soldiers, wrote Robert Nichols, “whose feet, hands, and side / Must soon be torn, pierced, crucified.” Nichols was moved to poetry by attending a Mass on his way to the Front: “O people who bow down to see / The Miracle of Calvary, / The bitter and the glorious,” he pleaded, “Bow down, bow down and pray for us.” Few were more direct than the American Catholic poet Joyce Kilmer. Killed by a sniper in late July 1918, Kilmer left behind a soldier’s prayer that begins, “My shoulders ache beneath my pack / (Lie easier, Cross, upon His back).” In “The Redeemer,” Siegfried Sassoon says twice that a soldier “was Christ”: one staggering beneath his wooden burden as Sassoon’s unit rebuilt a trench (“He faced me, reeling in his weariness, / Shouldering his load of planks, so hard to bear”); the other the face of a rotting corpse lit by a flare (“His eyes on mine / Stared from the woeful head that seemed a mask / Of mortal pain in Hell’s unholy shine”).

Sassoon’s doomed friend Wilfred Owen took inspiration from a crucifix corner near the Ancre River in France: “One ever hangs where shelled roads part.” (That poem became the text for the “Agnus Dei” in Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem: “In this war He too lost a limb, / But His disciples hide apart.”) Later, as he described training his men in England, Owen reproached himself for having to teach “Christ to lift his cross by numbers, and how to adjust his crown… With a piece of silver I buy him every day, and with maps I make him familiar with the topography of Golgotha.”

Owen wrote that description to Osbert Sitwell, whose sister Edith later wrote one of the most famous poems of the Second World War. In “Still Falls the Rain,” the bombs of the Blitz fall “With a sound like the pulse of the heart that is changed to the hammer-beat / In the Potter’s field, and the sound of impious feet / On the Tomb…” Such raindrops land at “the feet of the Starved Man hung upon the Cross,” where “the sore and the gold are as one.” Like Owen’s crucifixion poem, “Still Falls the Rain” was later set to music by Britten. Canticle III premiered in 1954, a year before Sitwell was formally received into the Catholic Church.

With an eye to Good Friday, I’ll just leave you with one final example of the theme: David Gascoyne’s “Ecce Homo.” Though written just before the war as a response to Fascism (“the centurions wear riding-boots, / Black shirts and badges and peaked caps, / Greet one another with raised-arm salutes”), Gascoyne’s suffering servant comes to mind whenever I struggle for words to describe a war that killed at least fifty million people — whenever, for that matter, I struggle with the reality that smaller wars afflict humanity still:

…He is in agony till the world’s end,

And we must never sleep during that time!

He is suspended on the cross-tree now

And we are onlookers at the crime,

Callous contemporaries of the slow

Torture of God. Here is the hill

Made ghastly by His spattered bloodWhereon He hangs and suffers still…