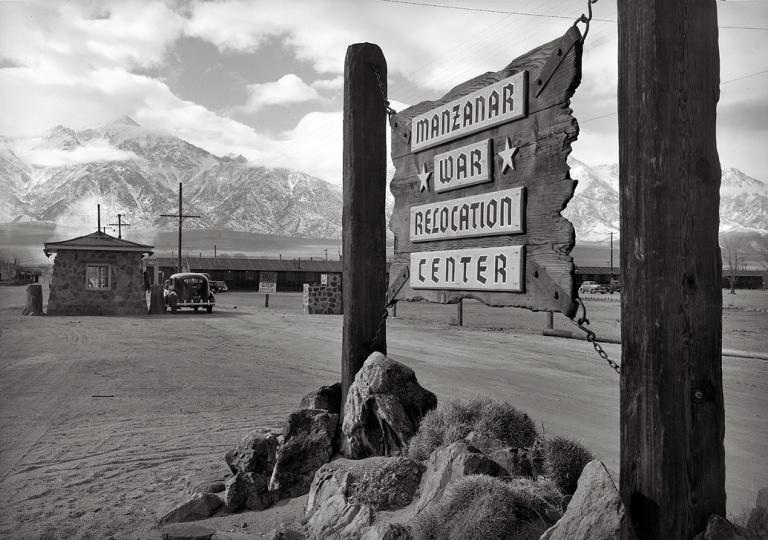

This past weekend, nearly 2,000 people made the annual pilgrimage to Manzanar, one of the concentration camps where the U.S. government incarcerated Japanese Americans during the Second World War. The pilgrimage was partly an act of historical commemoration: this year marked the fiftieth anniversary of the first pilgrimage to Manzanar, and 77 years have passed since President Roosevelt’s issuing of Executive Orders 9066, which authorized the forced removal of thousands of Japanese Americans on the West Coast.

But in 2019, the people who participated in the pilgrimage to Manzanar made clear that they were undertaking this journey not simply to tell the story of injustices committed against Japanese Americans in the past, but to bear witness to injustices committed against other vulnerable groups in the present. Participants expressed support for migrant children incarcerated at the U.S.-Mexico border, concern for African Americans targeted for racial profiling, solidarity with American Indians defending their land rights, and opposition to the restrictive immigration and refugee policies promoted by the Trump administration. According to Bruce Embrey, co-chair of the Manzanar Committee, the history of Japanese American incarceration offers important lessons for Americans grappling with the most important issues of today. “If we could go to Manzanar and just celebrate the contributions and remember the sacrifices that our community made, it would be wonderful,” he said. “But we can’t because [now] we’re more relevant than we care to be.”

In recent years, Japanese Americans have been particularly vocal in their support for Muslim Americans, whom they see as suffering the same hostility and injustice that they experienced in the 1940s. At this weekend’s pilgrimage, as well as in other demonstrations in recent years, participants drew clear parallels between the anti-Japanese hatred during the Second World War and the Islamophobia of today’s war on terror. For example, the grassroots organization Vigilant Love—which formed in the wake of the San Bernardino shootings to counteract Islamophobia and is led by Japanese American and Muslim American women—chartered two buses for the four-hour journey from Los Angeles to Manzanar. And in the afternoon, Muslim American pilgrims gathered to pray, amid the desolate desert landscape and the cheerful melodies of Odori, traditional Japanese dance music. Their prayers were not the only demonstration of religion at the event; an interfaith service also united Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and Shintoists, who together laid flowers at a Manzanar cemetery.

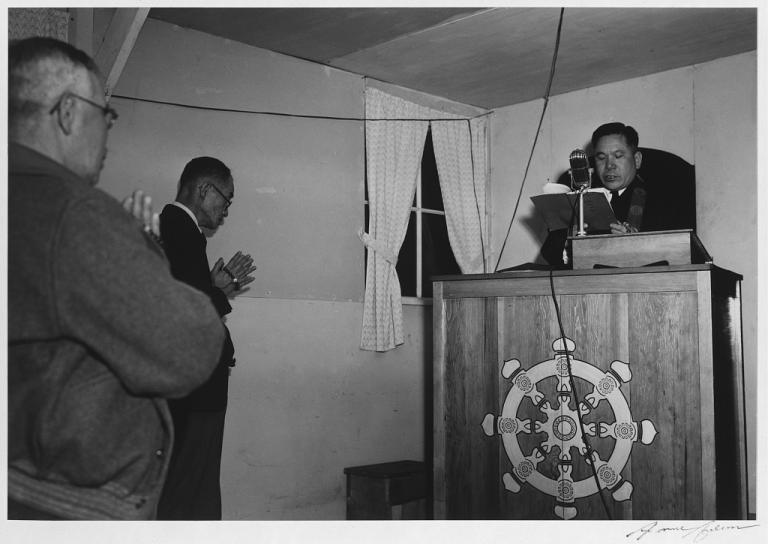

These acts of communal prayer and worship, as well as the ritual of the pilgrimage itself, offer an important reminder to pay attention to the religious dimensions of Japanese American and Muslim American experiences. Both scholarly and popular media generally interpret Japanese American incarceration and Islamophobia as expressions of racism and xenophobia. This analysis is important, but what about religious hostility? The religious dimensions of Japanese American and Muslim American experiences, and the complex and long-standing connections between racial and religious animus more generally, are often overlooked.

However, new historical scholarship by Duncan Williams, Professor of Religion and East Asian Languages and Culture at the University of Southern California, offers fresh understanding of Japanese American incarceration as a deeply troubling instance of government-sanctioned religious bigotry. As Williams argues in his new book, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard, 2019), the U.S. government targeted Japanese Americans not only because they were racial outsiders, but also religious outsiders whose Buddhism and Shintoism was viewed as “a national security threat.”

Williams argues that seeing Japanese American incarceration through the lens of religion is important, but long overdue, in part because of the “underlying presumption of America as a white and Christian nation.” He writes,

[W]hile it has become commonplace to view [Japanese Americans’] wartime incarceration through the prism of race, the role that religion played in the evaluation of whether or not they could be considered fully American—and, indeed, the rationale for the legal exclusion of Asian immigrants before that—is no less significant. Their racial designation and national origin made it impossible for Japanese Americans to elide into whiteness. But the vast majority of them were also Buddhists; in fact, Japanese Americans constituted the largest group of Buddhists in the United States at the time. The Asian origins of their religious faith meant that their place in America could not be easily captured by the notion of a Judeo-Christian nation…Religious difference acted as a multiplier of suspiciousness, making it even more difficult for Japanese Americans to be perceived as anything other than perpetually foreign and potentially dangerous.

Ultimately, most white Americans saw the United States as a white nation and did not view Japanese Americans as legitimately American people, and at the same time, most white Americans saw the United States as a Christian nation and did not view Buddhism as a legitimately American religion. In the early decades of the twentieth century, and particularly during the Second World War, these circumstances meant that Japanese American Buddhists and Shintos, being neither white nor Christian, were seen as “not only a threat to national identity, but a threat to national security.”

Williams points to numerous examples of how religious difference functioned “as a multiplier of suspiciousness” throughout the Second World War, and even well before it. During this period, the U.S. government and military believed that Buddhists and Shintos were a powerful anti-American block within the Japanese American community. In the 1920s and 1930s, several military reports warned that Buddhist and Shinto institutions in Hawai’i “retarded” assimilation into American culture and were “military liabilities.” Moreover, one Office of Naval Intelligence report, prepared by the Counter Subversion Section and published only three days before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, declared that Japanese American Buddhists and Shintos “provide excellent resources for intelligence operations, have proved to be very receptive to Japanese propaganda, and in many cases have contributed considerable sums to the Japanese war efforts.” However, the declaration that Japanese American Buddhists posed a threat to national security was contradicted by military reports that came to opposite conclusion. According to another ONI report from 1939, the majority of Japanese Americans, whether Buddhist or Christian, would likely be loyal to the United States in the event of war.

The U.S. government and military regularly surveilled Japanese American Buddhist and Shinto communities it suspected of spying. As Williams explains, there was no evidence to support these accusations of disloyalty. Most of the government and military suspicions focused on rather small actions—for example, efforts by Japanese American Buddhist women to pray for and send care packages to Japanese soldiers. These were not unlike actions undertaken by Italian Americans who supported Mussolini throughout the 1930s. However, as Williams explains, these gestures, when performed by Japanese Americans, “heightened suspicions that [the Japanese American community] was a breeding ground of Japanese militarism and anti-Americanism.”

Williams also discusses how the U.S. government began “compiling registries of potentially subversive Japanese” nearly two decades before the Second World War. In 1922 the FBI published a report, Japanese Espionage—Hawaii, which identified Japanese American people suspected of disloyalty; many were Buddhist priests. Later, in 1936, President Roosevelt directed the military to create a secret list of potentially subversive Japanese people who could be detained, if necessary. In a confidential memorandum, Roosevelt wrote that “every Japanese citizen or non-citizens on the Island of Oahu who meets these Japanese ships or has any connection with their officers or men should be secretly but definitely identified and his or her name placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp.”

These efforts to surveil and compile registries of Japanese American Buddhists and Shintos meant that the U.S. government was, as Williams puts it, “poised to execute a roundup of listed individuals within hours of any national emergency.” That national emergency occurred on December 7, 1941, the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor. By that point, the U.S. government possessed the information and resources it needed to take immediate measures against Japanese American Buddhists deemed a threat to national security. The first person the FBI arrested—Bishop Gikyo Kuchiba, head of the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist sect in Hawai’i—was arrested at 3 p.m. on December 7, mere hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Kuchiba was one of nearly two hundred Japanese American Buddhist and Shinto priests arrested by the FBI.

It is well known that the U.S. government treated Japanese Americans differently from Italian Americans and German Americans, indicating that racism intensified wartime hostility. But Williams points out that the U.S. government treated Japanese American Buddhists far worse than Japanese American Christians. Hundreds of Japanese American Buddhist and Shinto priests were arrested after Pearl Harbor; in contrast, only a handful of Japanese American Christian leaders were arrested. This and other examples suggest that religious hostility, and not racial hostility alone, animated the actions of the U.S. government and military during this period.

To be sure, American Sutra is not simply a story of how Japanese American Buddhists were the target of racism and religious bigotry. It is also a story of the spiritual resilience of Japanese Americans, of the adaptations and transformations they experienced throughout their incarceration, and of the importance and fragility of religious freedom in the United States.

However, American Sutra’s chronicling of how the U.S. government treated Buddhism and Shintoism as dangerous alien religions is perhaps its most compelling—and unnerving—contribution. It is clear from the section titles of the opening chapter—“Buddhism as a National Security Threat,” “Surveilling Buddhism,” and “Compiling Registries”—that Williams’ history of Japanese American incarceration speaks directly to the treatment of Muslim Americans in the present moment. As Reza Aslan observes, “Reading this book, one cannot help but think of the current racial and religious tensions that have gripped this nation—and shudder.”

As the pilgrimage to Manzanar last weekend reveals, the history of Japanese American incarceration can be connected to a wide variety of injustices in the United States today, from racial profiling to draconian asylum policies. But in calling attention to the religious hostility that shaped Japanese American incarceration, Williams’ American Sutra invites Americans to reflect anew on an often overlooked matter—the religious, and not merely racist, hostility that targets vulnerable populations today. Americans love to believe that their country is a land of religious freedom. History suggests, however, that it is also a land of religious hate.