This is Part II of an interview with David C. Kirkpatrick, author of A Gospel for the Poor: Global Social Christianity and the Latin American Evangelical Left. For Part I, click here.

–David R. Swartz

***

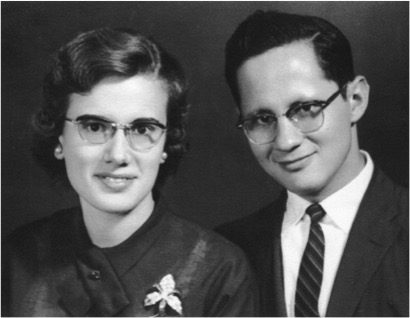

You appear to be one of the first to highlight women in the development of the Latin American Theological Fraternity. How does the narrative change when Catharine Feser Padilla is included?

Some have attempted to make this a story of North vs. South or “the Rest vs. the West.” The influence of Catharine Feser Padilla problematizes attempts to weaponize the narrative and use it for tribal vendettas. For post-war global evangelicalism, the story was always multidirectional and diverse—transcending nationalities and borders.

Catharine’s story also confirmed for me the need to interrogate sources. As historians, we cannot uncritically receive narratives and documents that enter established archives—especially within fraught religious, racialized or gendered spaces. Perhaps surprisingly, Catharine, as a female American missionary, actively sought to conceal her own influence in order to expand it. She navigated the expectations and restrictions of conservative evangelical spaces, while working behind the scenes to push social Christian ideas. Her influence was immense, while we may never know its full extent.

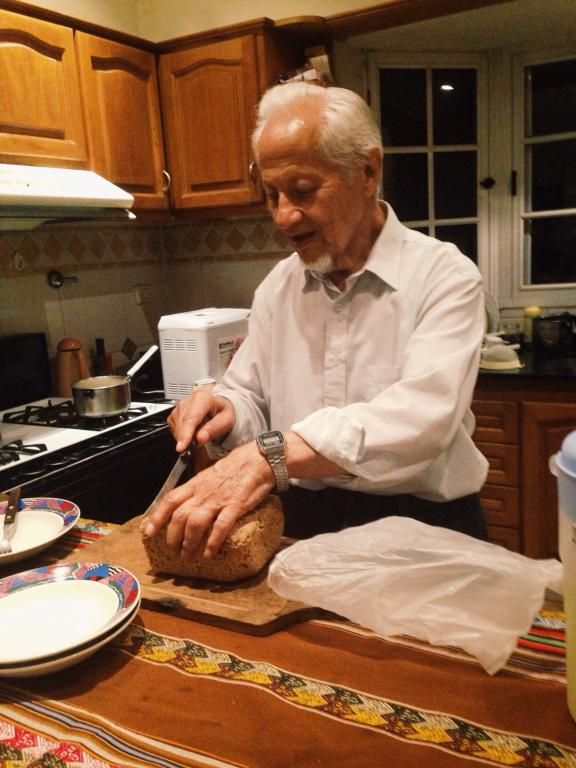

My initial hypothesis was confirmed during my first day of interviews with René Padilla in his Buenos Aires home. He gave a passing comment that Catharine, his spouse of almost 50 years, had edited “nearly everything [he] wrote”, including papers at global gatherings. Translation, of course, is never a neutral exercise but always involves interpretation. I began to ask how her own stamp marked Padilla’s thinking from the outset. At a very basic level, Catharine provided a bridge for a non-native speaker like René Padilla to communicate his ideas fluently. But more importantly, she pushed Padilla leftward politically and theologically. She also gave him the license to accelerate a fierce critique of American foreign policy. Her love of Latin America kept Padilla in the region long after close colleagues like Escobar and Costas left for positions of influence in the United States and Canada.

(I am also grateful for Dana Robert’s work and friendship in helping excavate this story. While I knew I wanted to explore Catharine’s fascinating and hidden influence, I am grateful to a coffeeshop conversation with Dana for the framework to understand it.

One of the challenges of writing transnational history is language and travel. What were some of the challenges and rewards of traveling abroad and working in Spanish?

Writing this book was deeply enriching for me. The diverse people I met, the gripping stories I heard, and the indelible experiences I had will live with me forever. In terms of research, Spanish was indispensable given the contested and transnational space that the main characters operated within.

In a story like this one, only dealing in English sources would have severely distorted the narrative—especially given the power dynamics between Latin America and the United States. Many of the Latin American leaders I interviewed are bilingual. For me, interviewing them in Spanish was an intentional choice to allow them to tell their story in their native language. This created more work for me, as the book is written in English, but I think allowed for a more rich and accurate narrative. More importantly, I think, I was constantly aware of my own positionality as an American researcher, especially over the question of power balance. As a white American male, I wanted to shift the power as much of it toward my Latin American informants.

Beyond my positionality, the Spanish research produced some surprising and fruitful discoveries. Padilla and Escobar, for example, often used their bilingualism to their own advantage. There are even a handful of examples in the book where they either changed the meaning or gave alterative translations of their fierce critiques of American evangelicalism. This is simply one example where they sought to obscure the white American gaze across the border and carve space for their own contextual thinking. On a textual level, most of their writings are Spanish documents that remain untranslated. Comparing writings in Certeza magazine against Christianity Today, for example, produced some fruitful discoveries that the book explores.

Who is the most complex or intriguing character in your book?

Exploring René Padilla’s life and influence was fascinating to me. Padilla’s story is an improbable one—from an impoverished Ecuadorian family, to Wheaton College and Manchester University, to speaking truth to Billy Graham on the global stage. Padilla’s story was both typical of Protestant evangelical minorities in Latin America and a-typical in terms of its trajectory. He was stoned as a child for attempting to enroll in a local school as a Protestant, dodged assassination attempts as he planted churches, and endured multiple arson attempts made on their homes and churches—dozens of evangelical church buildings and homes were burned down around them. To this day, Padilla bears scars from stones thrown at him as he walked down the streets of Bogotá, as early as age seven. René Padilla’s story demonstrates the long reach of evangelical networks that transcended borders, class, race, and language. I hope the reader finds his story as gripping as I did.

Perhaps I shouldn’t ask this of a historian, but what is at stake here? If you were to write a “Concluding Unscientific Postscript” that was more normative than descriptive, what would you say?

One of the biggest challenges facing American evangelicalism today is this: “How will its leaders and churches respond to the increasing diversity of the United States?” Unfortunately, evangelicals—and Americans more broadly—are often incapable or just unwilling to carefully mine their own history for direction. In this case, key insights into questions of justice, diversity, inclusion, and mission might be found in recent evangelical history. In other words, these questions are neither new nor unexpected, and many wonderful insights might be found within fraught Cold War tension over race, power, and foreign relations. Evangelicals can learn from their own successes and failures, timidity and courage, paternalism and partnership that dot this story in A Gospel for the Poor.

In the United States, evangelicalism is facing a crisis of identity. While many prominent leaders have denounced white supremacy and racial bomb-throwing, challenges of diversity, inclusion, and justice remain. How can they remain faithful to their history and mission while addressing monumental challenges ahead? Perhaps part of the answer lies in their own history south of the Rio Grande. An alternative history of evangelicalism—and definition—arises when seen through the eyes of non-white evangelicals. Perhaps an alternative future arises alongside it.

In the United States, evangelicalism is facing a crisis of identity. While many prominent leaders have denounced white supremacy and racial bomb-throwing, challenges of diversity, inclusion, and justice remain. How can they remain faithful to their history and mission while addressing monumental challenges ahead? Perhaps part of the answer lies in their own history south of the Rio Grande. An alternative history of evangelicalism—and definition—arises when seen through the eyes of non-white evangelicals. Perhaps an alternative future arises alongside it.

Anything else you would like to tell your readers?

As a writer, there are few joys greater than hearing from a reader. I would love to hear from you with comments, questions, or your own writing journey!