I’m not sure exactly when it happened, but shortly after I began teaching American history, I learned to love the bomb. More accurately, I learned to love teaching about the nuclear bomb. Maybe it was the day I suddenly realized that none of my students knew what USSR stood for (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics!)—because they were all born after the Cold War. Maybe it was the day I realized I had shown the “Duck and Cover” film enough times that I could now sing its jingle by memory.

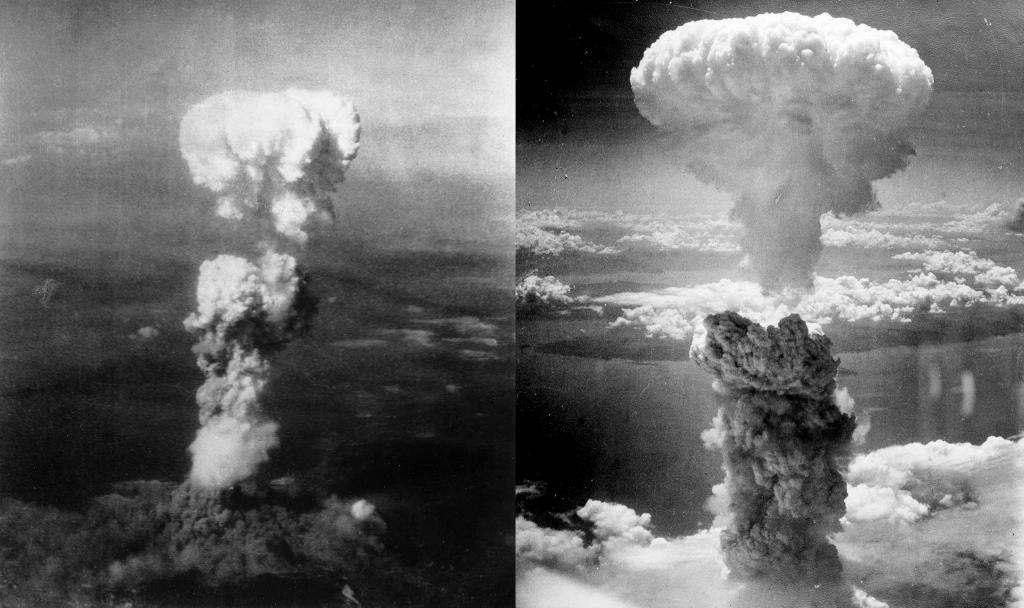

But it was probably the day I was hit by the emotional force of the fact that a nuclear bomb has been dropped in combat only two times: August 6 and 9, 1945. Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Humanity has been in possession of nuclear weapons for almost three-quarters of a century and has managed to only use them aggressively that one week. I am the sort of Christian who has a pretty robust view of human depravity, so I was struck by what a grace this is. And by the fact that it may not always be the case.

So I added a goal to my American history survey class: to give my students a sober assessment of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. They are voting citizens of a country with one of the largest stockpiles, but there has not been a major nuclear scare in their lifetimes. They have small yet real power over the bomb’s use, but no emotional grasp of the weightiness of that responsibility.

Here is the situation in numbers: On August 6, the American plane Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb Little Boy on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, killing approximately 40,000 people instantly. In the next few weeks, 100,000 more died from radiation poisoning or burns, and the total climbed to around 200,000 by 1950 as tens of thousands more succumbed to radiation complications. The Japanese government did not surrender after the initial drop, so on August 9, the American plane Bockscar dropped the atomic bomb Fat Man on the Japanese city of Nagasaki—to prove the nation could keep them coming—killing approximately 70,000 more people. In 1949, the Soviet Union developed their own atomic weapons. In 1952, the United States developed a far more powerful hydrogen bomb. In 1955, the Soviets got their own. Today, five countries with declared nuclear arsenals are bound by a nuclear non-proliferation treaty: (in order of first weapon test) the United States, Russia (formerly the Soviet Union), the United Kingdom, France, and China. Several other nations have suspected nuclear arsenals.

When I teach about the 1950s, I hit my students hard with the fact that people at that time did not know that no one would use the bomb in warfare again as of the middle of 2019. They lived instead in constant, low-grade fear. I recently watched the 2018 mini-series adaptation of Agatha Christie’s murder mystery Ordeal by Innocence, published in 1958. Part way through, I realized that fear of the nuclear bomb was the central metaphor of this telling of the story (the murder victim had built a nuclear bomb shelter that featured prominently in the plot). The series added this detail—in the novel, the victim’s mansion served as a sanctuary from the regular bombing of World War II, not the potential nuclear bombs of the following decade. But Western governments were pushing the construction of bomb shelters during this time, and this detail captured well the mood of the 50s.

The previous pervasiveness of atomic fear came up again this past weekend, when I visited the Dior: From Paris to the World exhibit at the Dallas Museum of Art. In the collections of Christian Dior dresses organized under each head of the House of Dior, I spotted one from the 1950s that seemed Russian inspired, smack dab in the middle of the Cold War. I couldn’t believe it. Then I looked closer: it was designed by Yves Saint Laurent during the brief period when he was artistic director of Dior before starting his own competing fashion house: 1958–1960.

These were the exact years of a brief period of détente between the Soviet Union and the United States, a thawing of the normally chilly East-West international relations. In 1958, the Soviet Union unilaterally stopped testing nuclear weapons, as a gesture of good will. The United States followed suit. During this time, the only country to test an atomic weapon was—ironically—Dior and Saint Laurent’s native France, which had achieved nuclear capacity for the first time. This period of reduced fear ended when the Soviets shot down an American U-2 spy plane in 1960, and subsequently resumed nuclear testing in 1961. (While we’re mentioning cultural references, this is the event portrayed in the movie Bridge of Spies.)

Japanese artist Isao Hashimoto recently created a compelling video-game-style rendering of every atomic explosion in human history (all except Hiroshima and Nagasaki were tests). The “game” shows the location of each explosion, color-coded by the country that set it off, ticked off at the interval of one month per second. A running “score” tally at the top of the screen categorizes the number of explosions by country. Watching the simulation run from the beginning of 1958 through the end of 1961 gives you a visceral appreciation for what détente felt like. (I show this video in class.)

Another good emotional entry point into the power and ethical complexity of nuclear weapons is the Amazon Prime series Man in the High Castle, based on the 1962 novel by Philip Dick. I am an American historian who loves dystopian fiction, so this show is pretty much my sweet spot. (I am eagerly waiting for the fourth and final season to drop this fall!) The series takes place in an alternate timeline where the Nazis and the Japanese won World War II and split up the United States between them. The Germans, allied with the Japanese, won the war by developing the atom bomb first and dropping it on Washington, DC. So it’s the 1960s and all Americans are living under totalitarianism. Different forms—Japanese and German—on different coasts, but both are awful. And yet…there are some sympathetic characters in these governments, mostly in the office of an upstanding Japanese trade minister. Somewhere along the way in Season 1 we learn that one of his assistants is from Nagasaki—“a beautiful city.”

This moment is a kick in the gut. Our real timeline is a better world, no question. The world is far better for the fact that it was the Allies, not the Axis, who developed atomic weaponry first. Democracy is vastly superior to totalitarianism. But in the alternate, far worse timeline, this good man, his beautiful city, and its innocent civilians still flourish. Because the United States did not drop the bomb on them.

I teach the ethical debate over dropping the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Japanese government at the time was not nice, to put it mildly. They committed the Rape of Nanjing and the torture of Allied POWs. They were refusing to surrender, and a ground invasion would have killed many, many American soldiers—and quite a few Japanese civilians. But those civilians would not have been the target. Nuclear weapons kill civilians by definition—hundreds of thousands of them, not only on the spot, but also slowly and painfully by the effects of radiation poisoning.

Seasons 1 and 2 of Man in the High Castle reveal well how antsy the possibility of further nuclear warfare made even very bad people—quite a few Nazis in power were doing whatever it took to prevent further use of the bomb. It scared them that much. And that accurately conveys the sense of dread during the Cold War in our actual timeline.

In two weeks, we will commemorate the seventy-fourth anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. So next summer—the 75th anniversary in 2020—should provoke a number of retrospectives and reflections. It’s a good time to take seriously the responsibility we have as citizens of countries with nuclear arsenals—and to not take for granted these almost seventy-five years without nuclear war, but to pray for God’s continuing mercy.