Today we welcome Monica L. Mercado to the Anxious Bench. Monica is Assistant Professor of History at Colgate University, affiliated with Women’s Studies and Museum Studies. She will spend the 2019-2020 academic year in residence at Harvard Divinity School as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Women’s Studies and North American Religions in the Women’s Studies in Religion Program. Monica is currently at work on her first book, The Young Catholic: Girlhood and the Making of American Catholicism.

In the introduction to Brett Grainger’s new book, Church in the Wild: Evangelicals in Antebellum America, readers discover a portrait of early American lived religion that centers the great outdoors. If we have often ceded the natural world to histories of unorthodox, elite seekers such as the New England Transcendentalists, we lose sight of a wider range of religious and cultural experiences in which religious people made sense of their surroundings. “A pervasive curiosity about the natural world,” Grainger writes, marked nineteenth-century American evangelicalism. The American landscape, he argues, served “as a site of spiritual power, presence, and possibility.”

Although my own research focuses on a largely urban population of American Catholics, as a scholar of American religious history who lives and works in rural upstate New York, I couldn’t help but pull Grainger’s work off the shelf as soon as it appeared. Summer seems like the obvious time to contemplate the long history of American religion outdoors, and, perhaps, use Grainger’s insights to think through the intersection of religious institutions with the natural world at a site familiar to many of us: summer sleep-away camp.

* * *

As the end of the school year approached in May 1913, the Catholic magazine America noted “the summer camp for boys or girls is fast becoming an American institution.” Anxious about the possibility of their children attending ostensibly Protestant camps or recreational facilities, Catholic writers and educators urged their fellow laymen and women build new recreational possibilities for children that were both American and Catholic. While the potential of summer camps to reform and revitalize the Catholic boy was often the center of these conversations, Catholic girls and young women were also invited to participate in a range of new summer activities, and often made them their own.

The religious history of summer spaces—camps, retreats, vacation communities—has rarely been written as a Catholic one. Studies of Boy Scouts, Girl Guides, and the Camp Fire movement have long highlighted Protestant Christian influences on the great outdoors and camping’s benefits for children. A growing literature on Jewish summer camps traces the intersection of politics with religious and cultural identity. When Catholic historians, on the other hand, examine childhood and recreation, they almost always start with the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) movement of the 1930s, focusing on sports programs in city parishes, overlooking the many suburban and rural sites that many of these same Catholic dioceses were purchasing to set up camp. My own research on young women in the American Catholic church of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries suggest Catholic encounters with nature that shift the landscape of religious practice, if only temporarily, during the summer months. Could summer camp be a religious experience?

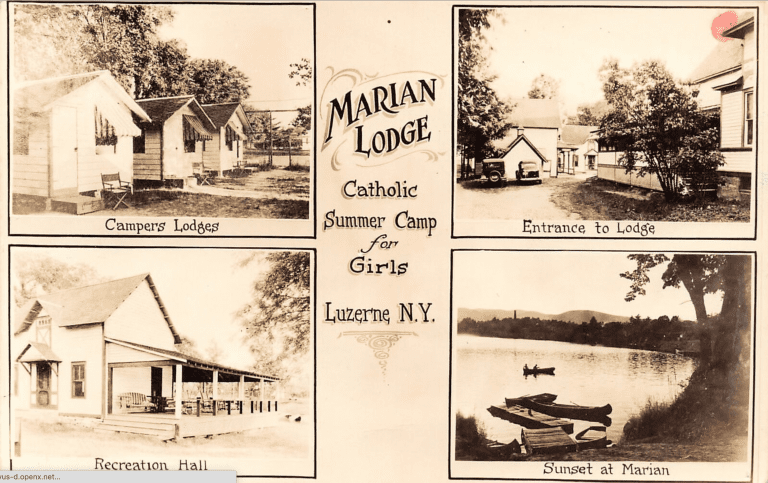

Upstate New York claims the site of the oldest continuously operating youth camp in the country—YMCA Camp Dudley (established in 1885 in the Catskill mountains and moved to the western shores of Lake Champlain in 1892, according to Adirondack Museum curator Hallie Bond). Nearby, historian Leslie Paris examined the records of Camp Jeanne D’Arc in the Adirondacks when writing her foundational study Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp. Beginning in 1922, the camp aimed to instill the saint’s “qualities of faith, endurance, courage, and confidence” in Catholic teenagers each summer. And 30 miles east, New York City Catholics founded the Catholic Summer School of America (or CSSA) near Plattsburgh New York on Lake Champlain, in search of “a valuable collective experience” for clergy, laypeople, and their families.

At Catholic camps and other summer spaces, religious ritual and new traditions coexisted in the outdoor retreat. Historians of summer camps talk about “ritual” and tradition–created through placemaking, competitions, songs, even the naming practices of camp staff. But these new rituals joined established religious ones. Camp chapels—both outdoor and traditional—were a part of many summer campers’ weekly experiences. As Hallie Bond’s history of Adirondack camps suggests, “outdoor chapels were part of a long tradition of seeing the Adirondack wilderness as a special abode of God.” But the plethora of “informal” “ecumenical” Christian services available to Protestant campers did not extend to Catholic campers—in part thanks to Canon Law, which requires sacramental practices to take place in a church, and not in the great outdoors. Catholic campers were required by their religion to attend Mass every Sunday in a consecrated church. Nondenominational camps took boys and girls to Mass in the nearest town; some Catholic summer camps built chapels on-site (for Masses typically celebrated by a visiting priest).

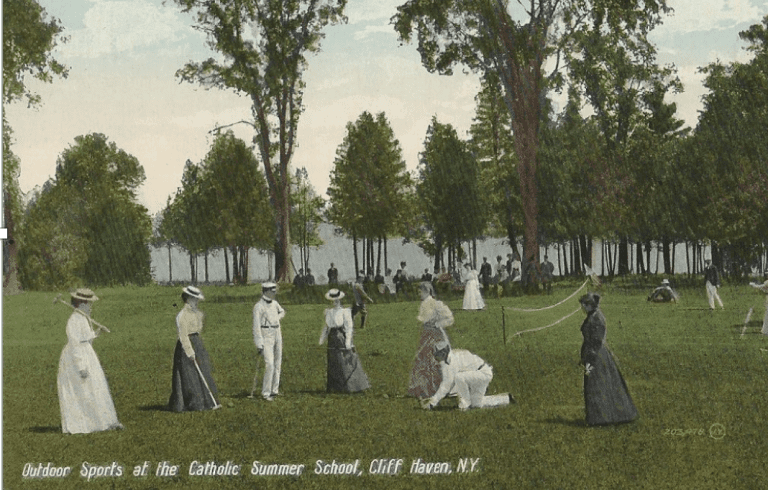

With camp archives scattered in private collections and Archdiocesan archives across the United States, it is perhaps useful to examine one of the most important, and understudied, camp-like spaces for girls in late nineteenth and early twentieth century America—this Catholic Summer School of America. While not a traditional sleepaway camp for young people, recently discovered photographs and other records of the CSSA suggest young women and their spiritual and social needs played an outsized part in summer activities. The croquet field, the bathing beach, and the social club–not the CSSA chapel–were the sites pictured on postcards and souvenirs from the site.

Founded by Catholic men who capitalized on the beauty and increasing accessibility of New York’s Adirondack region, and linked these conveniences to the geography of upstate New York “made sacred by the blood of Jesuit martyrs, and of patriots” the CSSA arrived on Lake Champlain in 1892, with breathless newspaper accounts announcing the formation of a school that would “rival Chautauqua.” Beginning in 1893, each Summer School session lasted six to eight weeks; the grounds were generally open from June 15 to September 15, with a full syllabus of weekly lectures published each spring to encourage attendance. Individual tickets for the full session cost six dollars apiece; any ten lectures cost a total of two dollars. Local hotels advertised rooms in Catholic magazines and newspapers, while a number of Catholic parishes and organizations began making plans to build permanent housing at the site. If the beauty of European cathedrals wooed well-heeled American Catholic travelers in earlier decades, Catholic Summer School boosters encouraged a new, homegrown travel destination amongst the pines of Lake Champlain—like a “fairy dream,” as one promotional pamphlet would later swoon.

Men’s understanding of this place for women rested on home and family, distinguishing between scholars and mothers. Warren Mosher, a founder of the CSSA described, “The whole assembly forms one large family… The scholar, as well as he who is in search of scholarship, can store his mind with the choicest treasures of history, literature, philosophy, theology, science and art. The mother of a family can be provided with a perfect home for herself and her little ones. Tired men of business can get useful, restful, and strengthening vacation. The young people of both sexes are afforded an unending round of social and athletic pastimes.” Certainly, the Summer School was family-friendly; Mosher’s description posits a peaceful retreat for Catholic mothers, and social and sporting opportunities for their teenage daughters.

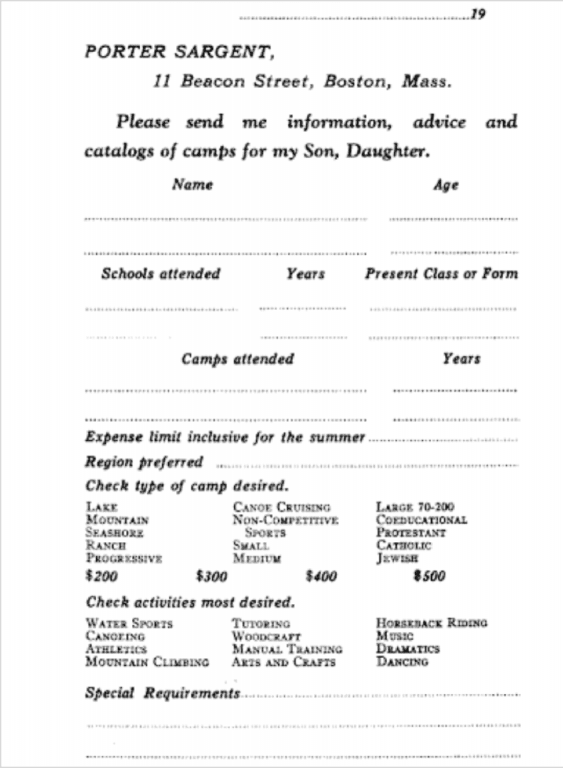

The Catholic Mosher’s Magazine marveled, “it is no wonder …that mothers find [the CSSA] a paradise for children. The camp provides an ideal life for youth. Indeed, the whole social and intellectual atmosphere is invigorating and inspiring. The article illustrated with images suggesting the CSSA was, simply, “a children’s paradise.” Other illustrations of “Summer School Girls” consistently depicted young women as vital to the daily life of the summer resort. This was, after all, a site that combined leisure with the gendered norms of Roman Catholicism and turn-of-the-century American culture. By the 1920s, the National Catholic Welfare Council reported that summer sleepaway camps were a “necessary adjunct” in the life of both American boys and girls. In the 1930s, families researching camp options could send away for more information on “types” of camps—Protestant, Catholic, Jew—as one popular camp catalog from the era suggests.

To talk about summer camp is to delve heavily into nostalgia, but I want to suggest we take seriously the religious histories of these sites as more American religious historians contemplate the role of nature in lived religion. How have summer camps—past and present–harnessed play and the natural landscape in the service of forming faithful boys and girls? What happens to religion out-of-doors?