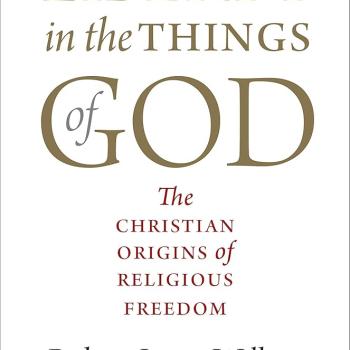

Book Review of Daniel Philpott, Religious Freedom in Islam: The Fate of a Universal Human Right in the Muslim World Today (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

After revoking the Edict of Nantes in 1685, and with it the civil and religious liberties that the law had afforded Protestants in his realm, Louis XIV boasted that France had become the most intolerant land in Europe. At the time, intolerance was seen as a political virtue—akin today to the notion of “zero tolerance.” It was a moral universe that would be upended in the following century when the American and French revolutions gave rise to a new political philosophy based on tolerance, secularism, freedom of conscience and religious liberty.

In the West, Islam is often criticized for not having experienced a similar revolution—a reformation, enlightenment or path to modernity that enshrines religious liberty as a fundamental human right. But these complaints too often come with scant understanding of Islamic theology or of the West’s own complicated path to religious liberty-a path championed by both religious and secular voices.

Daniel Philpott’s Religious Freedom in Islam provides a sober, hopeful reckoning with the plight and possibility of religious freedom in the Muslim world today. Based on copious research, comparative theological learning and a perspective at once global and historical, Mr. Philpott’s volume shines on all counts.

Mr. Philpott identifies two dominant positions in post-9/11 debates about Islam: “Islamoskeptics” see Islam as being incompatible with religious freedom, while “Islamopluralists” view it as a “religion of peace,” often citing the Quranic verse, “there is no compulsion in ¬religion (Qur’an 2:256).

According to Mr. Philpott, both sides exhibit defects. Islamoskeptics rightly note a deficit of religious freedom in many Muslim-majority countries—most visible in the laws against apostasy and in legal restrictions for non-Muslims. But while Islamopluralists are correct to say that such political behavior often has more to do with Islamism than with Islam per se, these voices tend to offer a theologically idealized version of Islam, not one attuned to facts on the ground. The reality, Mr. Philpott argues, is more complex and intriguing.

To help us see this reality, Mr. Philpott places Muslim-majority countries into three categories: religiously free states such as the various West African republics, as well as Lebanon and Kosovo; secularly repressive states led by Egypt and Turkey; and religiously repressive regimes, foremost Iran, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. While the third category validates the Islamoskeptics’ outlook, the second does not. In fact, it is a child of the West, exported to the Muslim world. “The secular repressive model,” Mr. Philpott argues, “emanates from a Western strand of thinking vivified in the French Revolution, which holds that the state must manage, control, and contain religion in order to make way for modern civilization.” The classic model is Turkey, founded in 1924 by Kemal Atatürk, who secularized society with an iron fist based on the French model. The Turkish word for secularism (laiklik) is derived directly from the French (laïcité). This assertive, statist secularism was later wedded to Arabic nationalism (and a patina of Islam) by figures such as Egypt’s Gamel Abdel Nasser and others inspired by him, notably the Baathist parties in Iraq and Syria.

The problem with this second model, Mr. Philpott argues, is that it feeds the problem it seeks to suppress: religious extremism. “In all of these cases,” the author ¬concludes, secularly repressive regimes “have contributed to the rise of violent Islamist groups.” Further, many devout Muslims have concluded that secularism (in its various guises) is to be eschewed as a Trojan horse sent by the West.

Convinced that religious freedom is a universal human right and that America’s First Amendment model protects these rights better than the French laïcité, Mr. Philpott counters that Islam has the capacity to embrace a shift in thought. He offers as an example the Catholic church’s path to religious freedom at the Second Vatican Council. “The Catholic tradition,” he writes, “provides testimony that a religious community that predates modernity and once was locked in conflict with modernity can embrace religious freedom and do so on the basis of its own religious commitments.” Catholic teachings on human dignity comport well with First Amendment guarantees of freedom, argued the American Jesuit theologian John Courtney Murray—an argument that won the day at the Council.

Mr. Philpott believes that something similar can happen in the Muslim world. Islam possesses the theological resources for such a shift, he argues, and devotes an entire chapter to articulating the “seeds of freedom”—in the holy texts of Islam, in the life of the Prophet Muhammad, and in the historical experience of Islamic civilization.

The book is not flawless. In his search for past examples, Mr. Philpott curiously omits the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1542-1605), who famously pursued a policy of universal peace with all faiths. One might also question the transferability of historical lessons from the Catholic Church to Islam; the former possesses a central decision-making apparatus and a theology of “doctrinal -development” in a way that the latter simply does not.

Still, “Religious Freedom in Islam” stands as a remarkable achievement—a gift of prudent, scholarly ¬authority amid shrill, polarizing debates. In his discussion of the Catholic church, Mr. Philpott helpfully reminds us that the past is not necessarily prologue for the future of religious traditions, and that judicious modifications, judiciously undertaken, can bring new life.

Mr. Howard, a professor of history and the Duesenberg Chair in Ethics at Valparaiso University. His latest book, “The Faiths of Others: Modern History and the Rise of Interreligious Dialogue,” will be published by Yale University Press in 2020.

***

This book review originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal (13 May 2019).