Today we welcome Hilde Løvdal Stephens to the Anxious Bench. Hilde is a Visiting Associate Professor of English at the University of Southeastern Norway. She holds a PhD in American Studies from the University of Oslo. Her first book Family Matters: James Dobson and Focus on the Family’s Crusade for Christian Home will we published by the University of Alabama Press in the fall of 2019 as part of the Religion and American Culture Series.

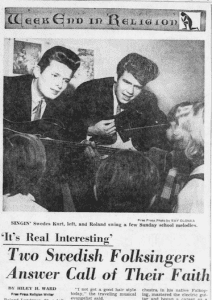

It’s not often that Swedish Pentecostal singers end up on the front pages of American newspapers. But in December 1965, the country duo Curt & Roland in the Detroit Free Press under the heading “Two Swedish Folk Singers Answer Call of Their Faith.” The young musicians Curt Petersen and Roland Lundgren were visiting Reverend Ralph Hart’s Liberty Temple Church, an independent Pentecostal congregation in Detroit, proudly preaching a message of happiness and joy in Christ.

Curt & Roland powerfully illustrate the Transatlantic connections between believers in the postwar years. As historians such as Hans Krabbendam and Uta Balbier have noted, evangelical groups seized the moment to save souls from Communism and the devil. Religious groups were well-connected through organizational and personal ties that had a long history. But such connections were perhaps even stronger in the postwar period. Following the end of World War II, a wave of American young evangelists flocked to Europe to, in their words, claim the continent for Christ. Billy Graham, for instance, visited Oslo in 1946 as part of a team of Youth for Christ evangelists.

The exchanges went both ways. Curt & Roland were just two of the many Scandinavian preachers and singers from many different groups who toured American churches in the postwar years. The pages of the Brooklyn-based Nordisk Tidende were filled with ads about church events featuring singers and preachers from the two countries. Churches and lay organizations provided a network that tied together immigrants and those who stayed at home. Thousands, if not millions, of Scandinavians had friends and family who had crossed the Atlantic in search of a better life. Into the 1960s, young Norwegian men and women would travel to the US in search of jobs and adventure. Many of the recent immigrants to settle in America were from the Norwegian and Swedish Bible belts. Visiting Scandinavian preachers gave immigrants a taste of home. Scandinavian immigrants had moved in droves to urban centers like Brooklyn, New York.

New York was an important place for Scandinavian Pentecostalism. Thomas Barratt, son of English immigrants to Norway, visited American churches in 1905 on a mission to raise money for his Methodist ministry in Norway. The spirit-filled meetings intrigued him, and when he visited a Pentecostal group in New York City in late 1906, he finally spoke in tongues himself. Thanks to him, the Pentecostal fire reached Oslo and quickly spread to other towns and cities just about a year after the revival on Azuza Street, Los Angeles, began. Scandinavian Pentecostals maintained strong ties to their US counterparts over the years. Pentecostal preachers moved between Norway, Sweden, the US, and the United Kingdom, building an imagined community of believers eagerly awaiting the return of Jesus and speaking in tongues to testify of the power of the Holy Spirit.

Those who did not travel could also get an even bigger dose of American Pentecostalism in the postwar years. From the mid-1950s, Scandinavian believers tuned in to listen to Oral Roberts’ healing services, first via the underground radio station Radio Luxemburg and later through IBRA radio, a station established by Lewi Pethrus who drew inspiration from his American colleagues. Many did not understand English, but still listened to the American preacher. Roberts boasted to having healed a woman in Norway who did not understand a word in English. “There is no distance in prayer,” he insisted.

When American healing preachers like William Freeman and William Barnham visited Norway and Sweden in the early 1950s, they seemed to have caused a rift in the Pentecostal movement. Some central Pentecostal figures welcomed their message. Freeman and Barnham preached in Filadelfia, Oslo, the largest Pentecostal church in Norway. Pastor Øivind Fragell was one of their staunchest critics. He warned against “American healing activities” in a pamphlet on the mortal threat to his beloved church. The conflict among Pentecostals was so strong that, according to the memoir of his son Levi Fragell, angry and upset Pentecostal believers burned the pamphlet on the town square of Kragerø.

If American healing preachers were controversial in Scandinavia, Norway’s most prominent healing preacher Aage Samuelsen made the tension even more pronounced. Samuelsen read Roberts’ Abundant Life magazine and preached the power of prayer to heal those who believed. His preaching style clearly borrowed from the flash and showmanship of American Pentecostal preachers. Echoing his American role models, Samuelsen shouted “Glory!” in English in the middle of his preaching and praying for healing.

Samuelsen’s Maranata movement stood in stark contrast to the evangelist Emanuel Minos (1925-2014), who became a standard bearer for Pentecostal middle-class respectability in the 1950s. Born to Egyptian and Greek parents in the Congo, Minos was adopted by Norwegian Pentecostal missionaries and brought to Norway as one of the first international adoptees in the country. A child preacher, he toured Scandinavia and the US with his parents. In the 1950s, Minos was part of a group of Scandinavian Pentecostal preachers who, similar to their pietist brethren in Lutheran churches, highlighted the depravity of human nature and called people to repent and turn to God. Minos boasted a degree from Oxford and a doctorate from an American university. Although the details surrounding his academic training remain muddled, Minos capitalized on his international academic credentials, however suspect, and offered a sense of cultural refinement to a movement that gradually grew away from its working-class roots.

Samuelsen was the son of working-class parents active in the trade union in Skien, a city with long traditions for being at the center of evangelical innovation in Norway. He was proud of his working-class roots. Unlike Minos, Samuelsen disliked the middle-class sensibilities of his fellow Pentecostals. He dismissed “fancy folks” and those with academic training. A tabloid newspaper ran a story on his influence, “Madness in the Name of God,” in December 1957. It quoted Samuelsen mocking ministers in the Church of Norway—“those dry and boring men of the church that just lie around and think about their own stomachs—they preach and preach but nothing happens.” The problem was, Samuelsen insisted, that they had nothing inside them. “They have their heads filled with dead theories.”

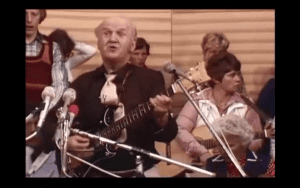

After Samuelsen was kicked out of the Pentecostal movement, he established the Maranata movement, which became famous for its lively music. The flamboyant and charismatic founder attracted scores of people to his up-tempo meetings. A seasoned performer from his pre-Christian days as a professional jazz musician. He called for a return to the energetic and expressive revivals of the first years of the Pentecostal revival. This meant pushing the boundaries for what was acceptable among the faithful, who were slowly building a more established church.

One of the more scandalous things Samuelsen did was to play the electric guitar. In 1957, the tabloid newspaper Dagbladet reported that Samuelsen had returned from the US with a brand-new electric guitar. The electric guitar became a staple of Maranata meetings in Norway and Sweden, where the Norwegian-born Arne Imsen became one of the figureheads of the movement.

Curt and Roland met and developed their musical skills in the Swedish Maranata movement. In 1963, the Swedish broadcasting network aired an edited recording of a Maranata meeting. Among the many musicians playing their electric guitars a young Curt can be seen playing, wearing a light jacket and with his hair combed back in the style of Elvis. Roland traveled throughout Europe and the US with Maranata preacher Daniel Bergagård. Together, Curt and Roland would join Bergagård as part of the Faith Brothers before they launched their own duo.

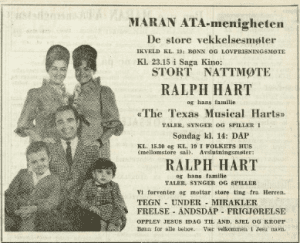

Maranata was also likely to be the place where Curt & Roland would meet the preacher who invited them to Detroit. In September 1964, newspapers advertised the Reverend Ralph Hart and his family’s visit to Oslo. The Musical Harts hailed from Texas but had by then settled in the Motor City. Having toured the US for years where they visited Southern transplants and reminded them of the sounds and styles from home, the Harts now combined Southern styles and Motown beats in songs like “Are you sure?” featuring Curt and Roland and their cover version of Andraé Crouch’s “I’ve Got Confidence.” While in Oslo, the Harts recorded an album with the same label as Aage Samuelsen and Curt & Roland.

The tabloid newspaper Verdens Gang sent a reporter to cover Hart’s meeting in Oslo. It is clear that their style did not match what the surprised reporter expected from a religious meeting:

Had their names been used for a circus advertisement instead of an advertisement for a religious meeting, it would have been a better fit with the family’s show. A massive choir of singers and clappers consisting of local pin-ups, seven guitars, castanets, a violin, a Hammon organ, and a piano “backed” them with everything necessary—from sensuous shaking of the hips to shouts of hallelujah and primal screams.

The reporter likened Ralph Hart to Elvis as the preacher slammed his guitar onstage before he fell on his knees, inviting people to come to the stage for healing.

Verdens Gang’s reporter may have been shocked by what he saw, but that effect might have been what Maranata was aiming for. Aage Samuelsen was a maverick who sought to shake people out of their lukewarm faiths to a spirit-filled and exciting life of glossolalia, healing, and other miracles. The rebuke from mainstream news outlets and the criticism from other Christians may have just fuelled the Pentecostal fire.

There was, however, much anxiety over the spiritual content of the rock’n’roll among at least some Swedish Pentecostals just like there was among American Pentecostals. Curt & Roland were worried about the false gods of rock music. They urged young Americans to reject secular groups like the Beatles. They warned that “that kind of stuff is from the devil,” in the pages of the Detroit Free Press. Jesus was a thousand times cooler than the Beatles would ever be, they insisted.

Curt & Roland became important to evangelical churches in Norway and Sweden that wanted to provide a Christian alternative to the devil’s music. Members of Maranata, Roland said in a 2011 interview, had not been quite welcome in other settings. But in 1970, the duo was invited to a more mainstream Pentecostal church and eventually became popular among other evangelical groups. Curt & Roland’s country gospel, lying somewhere between the Louvin Brothers and The Byrds, was a popular element to the many gospel nights arranged in churches and community halls. By Roland’s estimation, they spent an equal amount of time in Norway and Sweden.

The Christian music industry in Scandinavia went through a growth spurt and increased professionalization in the 1970s. Scandinavian-American connections remained important. Evie Thornquist, daughter of Norwegian immigrants to the US, for instance, became wildly popular among Scandinavian Pentecostals and other evangelicals. The Swedish Per Erik “Pete” Hallin ended up touring with Elvis, who praised the young Swede for his piano skills and his gospel songs, and he brought back the sounds of Nashville and Memphis to Scandinavian churches. In the years to come, American gospel music and Christian rock became important tools to create an evangelical identity. In the summers, Christian rock festivals drew together thousands.

Curt & Roland returned to the US a number of times, and they recorded three albums with some of the finest musicians in the world at the Columbia Recording Studios in Nashville. Just how this came about is hard to tell. But it is not impossible that the Musical Harts connection played a role: their daughter Linda Hart joined the Pentecostal Johnny Cash’s team of songwriters at the House of Cash. The Harts, then, might not have become major names in the US, but they might have played a very important role in shaping Scandinavian Christian music as they trained and encouraged two of the most influential Christian musicians in Scandinavia.