Like our recent guest blogger Emily Wenneborg, I’ve often found that hymns and history can “work together to deepen our love for Christ’s church.” But reading a recent history of the hymnal also reminded me why I appreciate the discipline of history itself: its seemingly impossible task, and how it nonetheless helps us to love neighbors in time who would be easy to forget.

At first, I was taken aback to open Christopher Phillips’ The Hymnal and realize that it wasn’t primarily about singing. “Who reads a hymnal?”, he asks right off the bat, recognizing how few of us know that it wasn’t until the 1850s that some hymnals began to incorporate musical notation. Even then, it took another generation for the hymnals we’d recognize to become commonplace among ordinary worshippers. But throughout the 18th and much of the 19th centuries, English-speaking Christians read and re-read hymns, carrying their hymnbooks between church (parishioners were expected to bring their own until the end of the 1800s) and home and school — where such books were crucial tools in early efforts at teaching children to read. “Hymn reading was a quietly central practice in Protestant worship for over a century,” Phillips concludes.

And sometimes not so quietly central. Indeed, hymnbooks were at the center of some of the most heated debates in this era of church history. Isaac Watts’ original 1707 collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs had appalled English Calvinists, but by the time of the 1830s split among American Presbyterians, “all of Watts, and nothing but Watts, would be the hill that the Old School… would choose to die on….” Likewise, hymnbooks were both weapons and battlegrounds in the 1840s Methodist war over slavery. A northeastern splinter group announced itself by publishing a new hymnbook that included twenty pages of abolitionist hymns (and about as many on temperance); when the remainder of the Methodist Episcopal Church split along sectional lines, the North and South immediately went to court over ownership of its lucrative publishing wing.

While he focuses on the hymnbooks of the white Protestant majority in Britain and the United States, Phillips pays attention to religious minorities as well. Indeed, “[f]rom African Methodists to Latter-Day Saints to Reform Jews, the production of a hymnbook was among the first official acts by community leaders to say to themselves and the world: we are now a people.” (Such projects also offered women opportunities for leadership. Joseph Smith commissioned his wife Emma to compile the first Mormon hymnbook, and a poet named Penina Moïse wrote many of the selections in the hymnbook for America’s first Reform Jewish congregation — Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina.) And one of the three “interludes” bridging the church, home, and school sections of The Hymnal tells the story of anti-Catholic riots in Philadelphia, where nativist mobs burned down two churches and a convent on a single night in 1844.

As of 1838, Philadelphia public schools started the day with readings from the King James Bible and hymns by Protestant writers like Watts and Charles Wesley, practices that made young Catholics “feel like religious others.” So Catholic publishers put out two hymnbooks for young people in 1844. John Cunningham, for example, meant his new Catholic Sunday School Hymn Book to “accustom children to the recital of pious canticles,” adapting a Protestant form to preserve young Catholics from “the contaminating influence of corrupt songs” — both secular and Protestant. After a second wave of the “hymnbook riots,” Philadelphia Catholics resolved to set up a system of parochial schools.

It’s just one of many examples of how the history of hymnals is bound up with the history of childhood.

Here too, the story starts with Isaac Watts. With most English and American Dissenters, he shared the “conviction that their children, girls as well as boys, should all learn the Word of God for themselves.” Of course, that meant Bible reading and memorization, but hymns, too. The next time you hear a children’s choir sing “Joy to the World” at Advent or Christmas, keep in mind that its author published a collection of Divine Songs for children in 1715, in order “to make children’s learning to read, as well as doctrine and morality, ‘a Diversion’ by using the pleasures of rhyme and image” — as an alternative to “joyless” primers of the day.

Hymnals would later enter American public and parochial schools, but even before formal schooling opened up to more children, such books were used to teach reading in the Sunday School movement. Here again, this kind of publishing opened doors to women like Ann and Jane Taylor, whose works (e.g., Hymns for Infant Minds, 1810) were “meant to be read, memorized, treasured, and (this point cannot be overemphasized) owned by children.” Though they honored the legacy of Watts, the Taylors “were literary pioneers who clearly saw the trajectory of the older tradition they followed in their work: one that took children seriously as readers, thinkers, and souls, and that created poetry especially for them….”

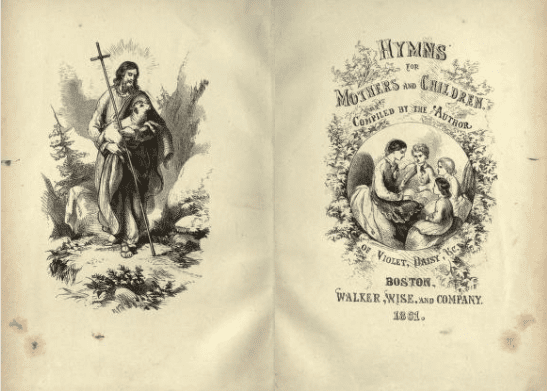

In 1861 a Unitarian named Caroline Snowden Whitmarsh published Hymns for Mothers and Children, a gift book whose texts came from the collections of children themselves. Especially in his coverage of such books by women for children, Phillips reminded me often of Peter Charles Hoffer’s notion that history is a paradox: both impossible and necessary.

Impossible, said Hoffer, because historians are tasked with mastering “a subject that is forever receding from our sight,” as memories fade, evidence vanishes, and interests change. In a chapter on Emily Dickinson (who seems to have been familiar with Caroline Whitmarsh’s hymnbooks), Phillips notes one particular version of the problem: “The ephemerality of children’s books, which Whitmarsh lamented, reflects the general lack of recording the history that passes between mother and child, from pregnancy and birth to care, early education, and the sharing of private reading from books precisely like Whitmarsh’s hymn collections.” Some of the most formative years in most all humans’ lives disappear without a trace.

Even when history leaves behind evidence and not ephemera, can we know how people read in the past? “Even in the present day,” Phillips observes, “the attempt to articulate what it is we actually do when we read—physically, cognitively, emotionally, spiritually—serves to show how enigmatic reading is. This mystery deepens when we look into reading of the past, since the marginal notes and written firsthand accounts of reading are by definition anomalies….”

Yet those anomalies can be instructive. It’s marvelous, for example, to watch a trained scholar interpret what 19th century churchgoers scribbled in their precious hymnbooks. Phillips’ chapter on this subject starts with Washington Irving sitting in a pew grieving his brother John — as we know from the brief note about John’s death that Washington added to his Book of Common Prayer. Not all such inscriptions were so weighty. Phillips explains how hymnbooks helped distract congregants as old as Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. — who spent particularly tedious sermons guessing at the authors of favorite hymns — and as young as Charley Longfellow — whose poet father kept him occupied by doodling humorous sketches in the same hymnbook he used for private devotions.

Phillips’ attention to children’s use of hymnbooks points back to the “necessary” part of Hoffer’s paradox. In my experience, even Christian historians rarely take seriously — “as readers, thinkers, and souls” — the young people whom Jesus went out of his way to bless. And Phillips’ centering of hymnwriters and editors like Emma Smith, Caroline Whitmarsh, and the Taylor sisters stands in stark contrast to the neglect of women’s history that Beth Barr recently pointed out at this blog.

So among its many merits, The Hymnal illustrates Beth Barton Schweiger’s notion that historians can use their considerable skills to practice love of their neighbors in time — especially those, like children and women, whose experiences may seem the easiest to forget.