All four of the New Testament gospels include the story of Peter’s denial of Jesus. In each gospel, after his final meal with his disciples, Jesus predicts that before the rooster crows (or crows twice, according to the most accepted manuscripts of Mark) Peter will deny him three times. A horrified Peter vows that he will never deny his Lord. Instead, he will die with him.

When Jesus is arrested, all of the disciples — according to Mark and Matthew — desert him and flee. At the same time, John and the synoptic gospels report that Peter follows Jesus at what he thinks is a safe distance, into the courtyard of the high priest. John adds the detail that Peter warms himself by a charcoal fire, alongside servants, slaves, and officials. His presence attracts scrutiny, and the others begin to ask him if he is one of Jesus’s followers. He denies it again and again, and the cock crows. ” At that moment, the Gospel of Luke adds, “The Lord turned and looked at Peter.” The synoptic gospels then narrate that Peter goes out and weeps bitterly.

Only the Gospel of John includes a bookend to the story of Peter’s denial. After the resurrection, the disciples are cooking a shore breakfast on a fire of burning coals. After this meal, Jesus three times asks Peter if he loves him, reminding him of his threefold denial. He then predicts that Peter will die as a martyr and tells him, “Follow me!”

The Gospel of Luke has Peter peering into the empty tomb, marveling at the linen cloths. Otherwise, though, the synoptic gospels leave readers with Peter as the disciple brought to tears by his denial of Jesus.

Peter’s denial of Jesus has served as the basis for several outstanding works of art, including those by Caravaggio and El Greco (my favorite, in this case of Peter’s tears after the crow of the rooster). Until recently, however, I did not know about early Christian depictions of Peter, the rooster, and Jesus.

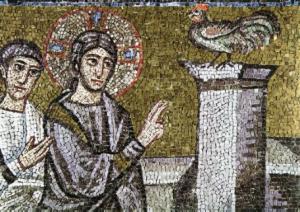

In his The Remembered Peter, Markus Bockmuehl briefly discusses early depictions of Peter in Christian art. Those included paintings of Peter walking on the water, but also frescoes and sarcophogi decorated with Peter and Jesus together with a rooster. Often, the rooster appears on top of a pillar, with Peter and Jesus on either side. See, for instance, the example from the Catacomb of St. Cyriaca. It seems that the images capture Jesus’s turning toward Peter, “convicting him without a word,” as Bockmuehl puts it.

Bockmuehl then explains the significance of the rooster within Christian iconography: “whereas in pagan art the rooster tends to symbolize light, victory and sometimes immortality, Christians unsurprisingly tend to link this with the theme of Christ’s resurrection.” In other words, the image of Peter and the rooster summons up not only thoughts of remorse and repentance, but also resurrection and renewal. As Bockmuehl summarizes, “the cock’s crow projects into the dark night of Maundy Thursday the bright daylight of Easter Sunday renewal.”

Bockmuehl also briefly mentions the significance of this motif in early Christian hymnody, notably that of Ambrose and Prudentius. Ambrose’s Aeterne rerum conditor (Maker of All, Eternal King) is the most prominent example. The “herald of the day” sounds off the end of night and the approach of day, bringing safety to travelers. It also recalls not only Peter’s denial of Christ, but also God’s forgiveness of that transgression: “it was at cockcrow that the very rock of the church washed white his sin.” God did not wait to forgive his sins until the risen Christ spoke with him. Ambrose concludes: “Look on us, Jesus, in our wavering, and seeing us correct us; for if you look on us our sins leave us and our guilt is washed away.” In other words, Jesus looked at Peter not to rebuke him, but to restore him. I like that. Drawing on the work of Svend Aage Bay, Bockmuehl suggests that the image of Peter’s denial and forgiveness had a particular appeal to “penitent believers who had lapsed under the duress of persecutions from Decius to Diocletian.”

The rooster retained its significance within Christian art for many centuries, adorning sarcophogi (see this lovely fifth-century example) and eventually becoming a favored symbol for weathervanes.

Although it is far away from my own fields of research, I love stumbling upon these less common but still significant motifs within early Christian iconography. They remind me of one of the ways that early Christians encountered the gospel, through visual representations of the Good Shepherd, the story of Jonah, the multiplication of the loaves and fish, and the Lord turning toward Peter. We Protestants have been so good at making the text of the Bible accessible to everyone, but perhaps less good at helping people within and beyond our churches have a visceral encounter with its stories. The image of the Lord turning toward Peter, or being with him at his darkest hour, is one of great comfort.

[Consider this post a sequel of sorts to an entry from several years ago about the ways that Christians perceived the gospel through their (inaccurate) understanding of the pelican].