On the banks of Mille Lacs, Minnesota’s second largest inland lake, there’s a small museum of Native American history. The center of the Mille Lacs Indian Museum is a cycle of life-sized dioramas depicting the seasonal economy of the Ojibwe, a people-group that spent its pre-reservation history moving from site to site depending on whether it was harvesting maple syrup, fish, vegetables, or wild rice. But while my family was waiting for that presentation on a recent visit, we walked around exhibits on the life of the Ojibwe in the 20th century.

I’m so glad we did. I received a welcome reminder that, as often as I teach the history of World War I, there’s much more for me to learn about how that conflict that affected the lives and beliefs of peoples around the world, including the Ojibwe of Mille Lacs.

The 1910 Census counted just over a quarter-million American Indians, up to 10% of whom served in the American military during WWI. That group includes 14 indigenous women who joined my great-grandmother Nelson in serving as nurses and 19 Choctaw troops who volunteered to communicate messages during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in a language the Germans couldn’t translate. Cherokee, Comanche, and other Indian soldiers would fill the same function later in 1918, anticipating the more famous Navajo “code talkers” of World War II.

Of course, what made that strategy effective is that centuries of European empire in North America left hardly anyone able to speak those languages. Many of the Native Americans who fought in WWI had been students at government-run residential schools, with military discipline reinforcing the goal of “assimilation through immersion” in European-American language and culture.

Yet those soldiers, marines, and sailors fought and died at higher rates than white Americans, motivated by a complicated patriotism. “I know I might get killed,” Owen Hates Him recalled thinking, having survived being gassed at Chateau-Thierry, “yet I know that I ought to do something for my country as we Indians are the real Americans, so I enlisted….” Joe High Elk, also of the Cheyenne River Sioux in South Dakota, found that he “could not tell the whole story” of the “hard times” he had seen in the climactic battles of the Argonne and St. Mihiel, but he felt that he “was doing my duty as a patriot and was fighting to save Democracy and do hope that in the future we Indians may enjoy freedom which we Indians are always denied.”

The two soldiers were among the 40% of American Indians who were not then American citizens. Both were interviewed by Joseph K. Dixon, a seminary graduate and self-proclaimed “authority on the American Indian” who had famously spent much of 1913 on a 20,000-mile “Expedition of Citizenship” to 89 reservations. “The Indian helped to free Belgium,” Dixon now argued, “helped to free all the small nations, helped to give victory to the Stars and Stripes. The Indian went to France to help avenge the ravages of autocracy. Now, shall we not redeem ourselves by redeeming all the tribes?” In part by interviewing 2,700 veterans like Joe High Elk and Owen Hates Him, Dixon helped secure passage of the American Indian Citizenship Act in 1924.

But the war also led indirectly to the creation of a ritual that helped these newest citizens resist assimilation, as the Mille Lacs museum’s current special exhibit explains.

And as soon as I read the inscription that explains the origins of the Jingle Dress Dance, I thought of Philip’s The Great and Holy War: How World War I Became a Religious Crusade. While I can’t remember him discussing Native American religion in that endlessly interesting book, it turns out that the jingle dress represents a North American version of an African story he did tell: that of the influenza pandemic that began in 1918, becoming even more deadly as it spread through military bases like the British one in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

The same ports and trading towns that had done such an impressive job in disseminating new religious ideas were now the transmission points for the lethal influenza. Faith and flu followed the same well-trodden routes. Influenza was soon raging across the continent, from Nigeria in the west to Ethiopia and Somalia in the east. Four or five million Africans perished.

Impervious to the efforts of Western doctors and as likely to kill Europeans as Africans, “the influenza disaster boosted nationalist and anti-imperial sentiment and discredited theories of white supremacy.” But it also “opened the door to new religious messages, at a time when the wartime withdrawal of missions meant that Europeans lost the ability to watch over the seeds they had sown. Across the continent, independent and prophetic Christian movements boomed.” For example, influenza helped sparked the Aladura movement in Nigeria, whose “prayer people” rejected Western medicine and placed their faith in divine healing. Philip called the Aladura, found today in both Africa and Europe, “the heirs of 1918.”

Something similar happened among Native Americans, whose tightly-packed communities (including those residential schools) were often decimated by the pandemic. Here again, influenza “opened the door to new religious messages.”

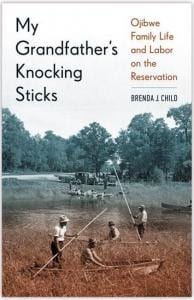

According to Brenda Child of the University of Minnesota, the jingle dress dance began when an Ojibwe girl became deathly ill in 1918:

According to Brenda Child of the University of Minnesota, the jingle dress dance began when an Ojibwe girl became deathly ill in 1918:

Her father, fearing the worst, sought a vision to save her life, and this was how he learned of a unique dress and dance. The father made this dress for his daughter and asked her to dance a few springlike steps, in which one foot was never to leave the ground. Before long, she felt stronger and kept up the dance. After her recovery, she continued to dance in the special dress, and eventually she formed the first Jingle Dress Dance Society.

While the dress and dance started with a man, it spread thanks to women who both risked their own lives to nurse the dying and danced in order to offer “spiritual sustenance” to the bereaved:

Once the influenza epidemic struck, women applied the ceremony like a salve to fresh wounds. They designed jingle dresses, organized sodalities, and danced at tribal gatherings large and intimate, spreading a new tradition while participating in innovative rituals of healing. Special healing songs are associated with the jingle dress, and both songs and dresses possess a strong therapeutic value. Women who participate in the Jingle Dress Dance and wear these special dresses do so to ensure the health and well-being of an individual, a family, or even the broader tribal community.

In a book that is both memoir and history, Child recalled encountering the Jingle Dress Dance as a child, when her Ojibwe grandmother participated in a midsummer powwow timed to coincide with the 4th of July, “which for us had little to do with patriotism, aside from the small parade of veterans who carried flags into and out of the arena.” Indeed, Child describes the jingle dress phenomenon as “an Indigenous, anti-colonial movement,” among the dances that the Office of Indian Affairs kept trying to suppress until the late 1920s. “Neither the promise of citizenship,” she observes, “nor the potential for reprimand discouraged” practices like the jingle dress dance. It spread from Ojibwe reservations to those of the neighboring Dakota, then later experienced a “remarkable, pan-tribal revival” in the late 20th century, with “the influenza” — and the war that spread it — “all but forgotten.”