No, this post isn’t about Charles Lindbergh. But it is set in Lindbergh’s — and my — home state.

In his famous 1893 address on the closing of the frontier, historian Frederick Jackson Turner recalled Eastern fears of a “West cut loose from her religion.” He quoted an 1850 editorial from a home missions periodical:

We scarcely know whether to rejoice or mourn over this extension of our settlements. While we sympathize in whatever tends to increase the physical resources and prosperity of our country, we can not forget that with all these dispersions into remote and still remoter corners of the land the supply of the means of grace is becoming relatively less and less.

So it’s no surprise that America’s frontiers have always drawn itinerant preachers. Most famously, thousands of “circuit riders” carried Wesleyan Christianity to the edges of post-revolutionary America, with such enthusiasm that early 19th century midwesterners claimed that bad weather days found nothing outside but “crows and Methodist preachers.” Later in the century, a different kind of itinerant preacher carried the means of grace into the deep woods of cold places like northern Wisconsin — whose “Pinery” inspired the editorial Turner quoted — and northern Minnesota — where my family spent the Labor Day weekend on a tour of state historical sites.

In Grand Rapids (not this one), we came to the Forest History Center, where historical interpreters take visitors through life in a logging camp, ca. December 1900. In the clerk’s office, one of our guides pointed to an extra bunk and explained that it was reserved “in case a sky pilot came to camp.”

Perhaps the actual religious historians who write for this blog know this term well, but it was new to me. So naturally I stopped listening to the tour, pulled out my iPhone, and looked up the relevant article in MNopedia:

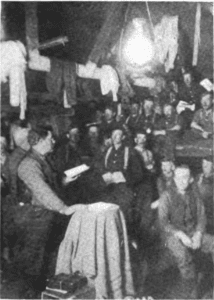

Working as a lumberjack in northern Minnesota was a difficult job with poor living conditions. Many loggers blew off steam by drinking, gambling, or visiting brothels. “Sky pilots,” or visiting ministers, tried to save the men’s souls and put them on the road to holiness rather than vice.

These itinerant preachers served itinerant flocks. Lumberjacks — many of them recent immigrants from northern Europe — moved from camp to camp, and camps themselves moved every season as logging companies deforested the North Woods, trying to satiate a growing economy’s insatiable demand for lumber. (At its peak, white pine loggers in Minnesota cut down enough trees to produce over 2 billion board feet of lumber.) In the Upper Midwest, the peak of the sky pilots’ ministry coincided with the peak of this industry, between 1895 and 1915.

(By the way, “sky pilot” can also refer to a military chaplain — like the one at the heart of The Animals’ song by that title. However it came to be attached to clergy on the frontier, that’s not exclusive to the Upper Midwest of the United States. It’s the title of an 1899 novel by Ralph Connor, the pen name of a pastor in Winnipeg who wanted to write a tale of evangelism and social reform in the foothills of Canada’s western frontier.)

Most famous among Minnesota’s sky pilots was Frank Higgins. Himself a convert of a frontier revival in rural Ontario, Higgins was pastoring a Presbyterian church forty miles southwest of Duluth when he was first invited to a logging camp in 1895. Within seven years, Higgins’ denomination had commissioned him to serve “the parish of the pines” full time, and he soon had seven or eight assistants helping him serve thousands of lumberjacks. “In bunkhouse and byway,” reported The Missionary Review of the World in 1915, Higgins “delivered his message of regeneration, in city and town he graphically told the narrative until the churches were awakened to participate in his unique labor of love…. the byways of the Minnesota forests have never known a more devoted and persistent traveler than this messenger to the ‘down and outs.’” When Higgins died later that year, the New York Times reported that he “had taken the Gospel to more than 30,000 of the roughest men in the world.”

Higgins and other sky pilots thundered against the evils of drinking, gambling, and sex (in local brothels, the MNopedia article clarifies, or “with each other”). But at the same time, wrote Minnesota historian Harold Hagg, “Higgins felt that the woodsman was sinned against as well as sinning” — lacking roots in society, without access to educational opportunities, and forgotten by established churches. So these pastors identified themselves as closely as possible with those workers. “I went out as a lumberjack,” wrote Higgins, “and did the things the men did.”

In the process, such preachers found themselves in the midst of a particularly heated labor-capital battle. While the sky pilots may have identified with the members of their flock, access to the camps required the support of employers. “The contractors and lumbermen themselves are taking a decided stand with us,” Higgins told a local newspaper in 1907. “They are realizing that it is to their best interest, financially and otherwise, to bring Christianity to the men. They have discovered that this class will do better and more work, will stay with them longer, and exert a strong influence for decency and order about the camp.” One of his assistants, a former lumberjack named Frank McCall, went on to preach in the Pacific Northwest, where one magazine celebrated in 1922 that “his work has done much to destroy the evil influence of the few radical leaders in the woods.”

Mainstream labor leaders had no interest in unionizing lumberjacks, but the Industrial Workers of the World attempted it in Minnesota just a year after Higgins’ death. (Unionization finally came in 1937, after a short strike, by which point the industry was operating at only 10% of its turn-of-the-century peak.) Wobblies viewed itinerant preachers much like United Mine Workers president Tom Lewis, who wrote disparagingly in 1910 of “listening to a sky-pilot orate about the ‘sweet bye-and-bye,’ while our internals were calling for something in the ‘sweet now-and-now.’” Or as the pro-Wobbly poet Joe Hill put it, in a labor anthem that parodied a popular hymn about “The Sweet By-and-By”:

Long-haired preachers come out every night

Try to tell you what’s wrong and what’s right

But when asked how ’bout something to eat

They will answer in voices so sweetYou will eat, bye and bye

In that glorious land above the sky

Work and pray, live on hay

You’ll get pie in the sky when you die