…the Salvation Army is both more and less than most people suppose it to be. The Army is more than blandly beneficial, more than a mere charity. It is a religious crusade, an evangelical Christian denomination; its sole purpose is to secure the redemption of lost sinners through faith in the Atonement of Christ. (Edward H. McKinley)

If you’re like me, you thought about the Salvation Army for two reasons last week.

First, you went to the grocery store or a mall and saw someone ringing a bell in front of a red kettle, inviting donations from passers-by. It’s the most iconic image of the Army: the ubiquitous symbol of its universally admired commitment to serve people around the world suffering from poverty, homelessness, disease, etc. This year Salvationists aim to raise $150 million through those kettles and bells.

But they will not receive money from one corporate sponsor. As you may also have seen last week, the Salvation Army featured in this CNN story about a fast food chain’s decision to change its philanthropic giving.

Chick-fil-A has announced that beginning next year it will no longer donate to Salvation Army and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA). Both organizations have taken controversial stands on homosexuality and same-sex marriage. https://t.co/X1HJ4Bd2FF

— CNN (@CNN) November 18, 2019

At least for now, Chick-fil-A Foundation won’t direct money to two Christian nonprofits: Fellowship of Christian Athletes and the Salvation Army, which last year received $115,000 in support of a program that gives holiday gifts to children. Commentators instantly made a connection with criticism that Chick-fil-A had received from gay rights activists. It had started with the company’s founders’ support of anti-same-sex marriage groups in 2011-2012, but turned more recently to philanthropic support of conservative religious organizations.

That news got me looking through the Anxious Bench archive, searching for a post that I could share with readers who might be confused to see that “anti-LGBTQ” headline in the season of red kettles and bell ringers. But remarkably, it seems that we’ve never written a post primarily devoted to the history of the Army.

I’m not sure I’m the best one to rectify that oversight. But one of the joys of blogging is that you have a built-in excuse to learn just enough about something to feel comfortable sharing your semi-ignorance with others!

Now, it’s not that I knew nothing of the Salvationist story before this month.

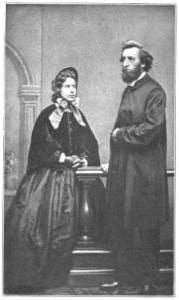

I knew it started with an English Methodist preacher named William Booth, who will feature prominently in a lecture I give next Friday on Christian responses to the Industrial Revolution. “My only hope for the permanent deliverance of mankind from misery,” he wrote in 1890, “is the regeneration or remaking of the individual by the power of the Holy Ghost through Jesus Christ. But in providing for the relief of temporal misery I reckon that I am only making it easy where it is now difficult, and possible where it is now all but impossible, for men and women to find their way to the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Booth argued that if people could not live even as well as a London cab horse — with “a shelter for the night, food for its stomach, and work allotted to it by which it can earn its corn” — they could never truly hear and respond to the Gospel. So he and his wife Catherine founded a relief mission in London in 1865, which took on the name of Salvation Army in 1878.

I knew that their Wesleyan roots have historically led Salvationists to emphasize both social and personal holiness. They warn about the dangers of alcohol and pornography, as well as racism and human trafficking. So I wasn’t too surprised to learn that today’s Salvation Army takes the position that “Scripture forbids sexual intimacy between members of the same sex.” While Salvation Army U.S.A. and its regional territories take pains nowadays to emphasize how they minister to and hire LGBTQ individuals, they have not retreated from their traditional stance on sexuality.

Finally, I knew enough about the history of the Salvation Army to nod vigorously when my wife first suggested we call our daughter Evangeline. Not only is it from the Greek for “good news,” but that was the name William and Catherine Booth gave to their fourth daughter, who followed her parents into leadership of the Army. Evangeline Booth was the first of three Salvationist women (so far) to hold the rank of General and one of the denomination’s founders in North America.

I knew all this. But I didn’t know much about the Salvation Army in the last 100 years. So I started by paging through some Salvationist perspectives on the denomination’s history: E. H. McKinley’s Marching to Glory: The History of The Salvation Army in the United States, 1880-1992 (2nd ed., Eerdmans, 1995); Henry Gariepy’s even more hagiographic Christianity in Action: The International History of the Salvation Army (Eerdmans, 2009); and Harold Hill’s more critical Saved to Save and Saved to Serve: Perspectives on Salvation Army History (Wipf & Stock, 2017).

But bearing in mind Kristin’s observations about the strengths and weaknesses of “insider history,” I spent most of my time reading Red-Hot and Righteous: The Urban Religion of the Salvation Army (Harvard University Press, 1999) by Diane Winston, a journalist and scholar who now holds a chair in media and religion at the Annenberg School.

I’m glad I did! While Winston doesn’t directly address Salvationist views on homosexuality (she did in this 2009 interview with NPR), her account helps me better understand a couple of tensions in the history of the Salvation Army that may be relevant to what happened last week.

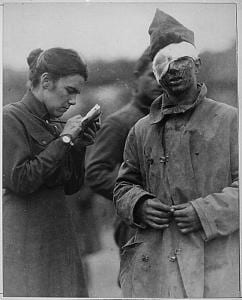

In Winston’s book, “issues of gender and sexuality came to the fore” not in later debates over same-sex marriage — her story ends in 1950 — but in the Salvation Army’s response to World War I, when an organization headed by a woman decided to send women (“lassies”) among the 250 Salvationists deployed to France. Known as “Sallies,” their service among American soldiers made them as iconic an Army symbol at the time as the red kettles are now.

But a complicated symbol, at once signifying “wholesome womanhood” and “the sexual ambiguity that lay between the spiritual and the secular.”

For Winston, the case of the Sallies illustrates how the Salvation Army’s commitment to “religionize secular things” has also meant that its soldiers often “blurred boundaries… Not content to transgress geographic borders, Salvationists defied symbolic boundaries, too.” For example, the sight of “uniformed women” in late 19th century Salvation Army parades “struck many New Yorkers as a violation of Christian norms.” In that 2009 NPR interview, Winston mentioned how one New York Times reporter warned readers “that if your daughter joins the army, she should kiss her respectability good bye.”

The “first Christian group in modern times to treat women as men’s equals” would not stop with women’s participation in parades. As it deepened its engagement with urban culture, a fundamentally conservative Christian organization would employ what for the time were transgressive methods. For while the Salvation Army continued to affirm the importance of personal (and social) holiness as it entered the Roaring Twenties, the uniform of the Sallies came to signal “a more provocative notion—the ability to put on or cast off an identity as easily as a new suit of clothes” — just in time for the arrival of an “age of flappers and sexual freedom.”

Yet even as Army leaders “allowed socialites to pose as models and showgirls to raise funds in uniform,” they insisted that “lassies themselves… hew to a proper image.” Salvationist women who tried to use “sexual charisma” to further their mission risked censure.

Women like Captain Rheba Crawford. “Feisty, attractive, and articulate,” writes Winston, Crawford “lived in Greenwich Village, liked pretty clothes, and plainly spoke her mind.” Not just “The Prettiest Girl in The Salvation Army” but a practitioner of William Booth’s preference for “red-hot” preaching, she drew a thousand a week to her open-air sermons on the steps of a Broadway theater owned by George M. Cohan. But after a policeman arrested her in 1922, Crawford was asked to resign her commission. While she accepted the “Army’s standing policy to avoid dispute and to frown on personal publicity,” she regretted having “to lay down the only weapons God gave me.”

The case of women like Crawford is just one example of a larger theme in Winston’s account: how an evangelical, Holiness denomination has often lived in tension with the fast-changing values of urban culture. For Salvationists, the challenge has long been how they can be “In the city but not of the city.”

With an account that starts in New York in 1880, Winston emphasizes how the Salvation Army “staked a claim to city life as no religious group had done before… Even in smaller cities and towns, the Army existed only insofar as it had a public presence.” Shaped by its roots in Holiness theology, the Salvation Army has always sought to “transform the secular world into the Kingdom of God” — by placing itself in the centers of culture… and so, not surprisingly, it finds itself in the midst of cultural debates.

With an account that starts in New York in 1880, Winston emphasizes how the Salvation Army “staked a claim to city life as no religious group had done before… Even in smaller cities and towns, the Army existed only insofar as it had a public presence.” Shaped by its roots in Holiness theology, the Salvation Army has always sought to “transform the secular world into the Kingdom of God” — by placing itself in the centers of culture… and so, not surprisingly, it finds itself in the midst of cultural debates.

And you could substitute the words economy and economic for culture and cultural. In Winston’s interpretation of its experience in the United States, the Salvation Army has been “both a symptom of and a catalyst for a new, evolving urban culture driven by commerce and fueled by consumption.” But you don’t get to be “one of the nation’s most successful charitable fundraisers” without having to wrestle with your relationship to an economy in which corporations play an outsized role in philanthropy. And you can’t keep “a strong symbolic claim not only on America’s purse strings but also on its psyche” without having to deal with consumers who might, as Tara Isabella Burton put it last week, envision “the spending of money as inextricable from affirmations of one’s values.”