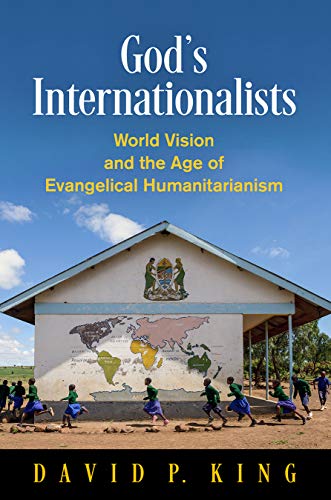

The evolution of an NGO’s bureaucratic structures as it positions itself theologically and organizationally in the worlds of religion and development does not seem like a recipe for a sexy narrative. But God’s Internationalists: World Vision and the Age of Evangelical Humanitarianism pulls it off. Here’s why this book works:

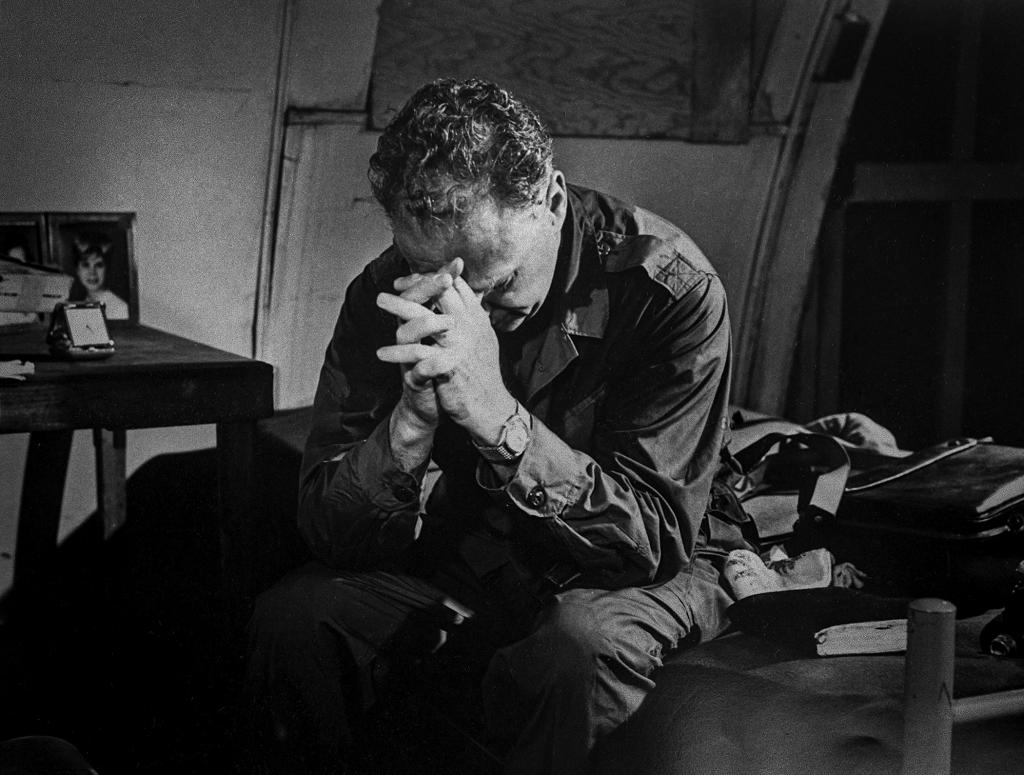

First, author David King, the Director of the Lake Institute on Faith & Giving at IUPUI, has good material to work with. The book’s main character, Bob Pierce, is quite a character. In building World Vision, he is impulsive, restless, oriented to action, and ambitious. He becomes a globe-trotting adventurer who neglects his family. Even when his wife, who has suffered a mental breakdown and is confined to a bed and pleads for him not to leave, he does anyway. She is persuaded by the evangelist Torrey Johnson to “release” her husband to the Lord’s call in China.

First, author David King, the Director of the Lake Institute on Faith & Giving at IUPUI, has good material to work with. The book’s main character, Bob Pierce, is quite a character. In building World Vision, he is impulsive, restless, oriented to action, and ambitious. He becomes a globe-trotting adventurer who neglects his family. Even when his wife, who has suffered a mental breakdown and is confined to a bed and pleads for him not to leave, he does anyway. She is persuaded by the evangelist Torrey Johnson to “release” her husband to the Lord’s call in China.

The passionate Pierce turns everything into an emergency, which says something important about Bob Pierce himself, the organization, and perhaps even something about evangelicalism generally. Consider this quote from Pierce as published in the Los Angeles Times:

“World Vision has a new complex computer system which diagnoses the failures of Christianity and prints them on a data sheet. . . . I can’t stand it. I love the early days when I was walking with widows and holding babies. When I began flying over them and being met by committees at the airport it almost killed me.”

If history is fundamentally about story, King succeeds here. Against all odds, he manages to make the history of this bureaucratic behemoth a rollicking tale of one man’s strength and weakness—and an organization’s fascinating response to the chastening of decolonization, Vietnam, and famine in Ethiopia.

Second, God’s Internationalists works because King does very good historical work, especially in two areas that historians work the hardest at: context and change over time. He first positions World Vision in the Cold War environment. Viewing the world through American eyes, founder Bob Pierce framed American intervention in Korea as that of a capitalist, democratic, Christian nation protecting the masses from atheistic communism. He also positions World Vision in the context of the development world and Western humanitarianism. What did respectability and professionalization look like as World Vision cooperated and clashed with the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, USAID, and the World Council of Churches? And finally, King contextualizes World Vision ecclesiastically. Where did World Vision fit amidst fundamentalism, neo-evangelicalism, and the mainline? I know the development world less well, but he’s spot-on with the Cold War and evangelical contexts of World Vision.

That Cold War posture, however, would change. He tracks how World Vision grew beyond the leadership of one man. “In the beginning there was Bob Pierce,” began one insider history of World Vision. “We used to say that Bob went around the world writing checks for needy situations and then wired home to tell people what he had done.” By the late 1960s World Vision, which was near bankruptcy, had been careening from crisis to crisis for nearly two decades. Pierce’s pulsating spirit was wonderfully energizing. But the vexing problems of imperialism, Vietnam, and world hunger could not be challenged by mere passion alone. In the late 1960s the board of directors unceremoniously removed the domineering, erratic Pierce as president.

The new leadership, surveying its global partners in order to discern future directions, discovered that global tensions pervaded internally as well. The work, directed from headquarters in Monrovia, California, to four support offices, ten field offices, and work in 36 nations, had become increasingly complicated, technical, and diverse. King narrates how this process of bureaucratic de-Americanization gave global evangelicals a platform to soften World Vision’s Christian Americanism and to redirect the organization toward a new methodology of long-term sustainability. We’re left with a compelling and ironic punchline: that World Vision, while not secularizing, adopts many of the same methods of its liberal mainline opponents. It’s a masterful chronicling of change over time.

Third, this book succeeds because the story of World Vision matters. So much of what has defined evangelicalism is global. And yet the historiography of evangelicalism has been dominated by national accounts of politics, culture wars, theology, and business culture. This transnational gap is now being remedied by historians such as Melani McAlister, Lauren Turek, Heather Curtis, David Kirkpatrick, and Ben Brandenburg. But minus Curtis and McAlister, even this wave of scholarship just now coming into print does not deal much with relief and development work, something that has been a significant preoccupation of American evangelicals for the last century. And until now, no one has written a comprehensive historical narrative on the largest and most important evangelical NGO of them all. Consequently, this book may be one of the most necessary interventions in American evangelical historiography in many years.

Thanks to King’s work, we now have a baseline history grounded in World Vision’s archives in Monrovia, California, and Federal Way, Washington. But, as Arlette Farge says in her book The Allure of the Archives, “History is never the simple repetition of archival content, but a pulling away from it, in which we never stop asking how and why these words came to wash ashore on the manuscript page.” In the case of World Vision, the words and images were collected mostly by powerful white evangelicals—and they tell important stories, most especially the story of how powerful white evangelical men narrate themselves.

Much more, then, remains to be written beyond this Western—mostly American—narrative that stars Bob Pierce, Stanley Mooneyham, and Bryant Myers. Indeed, King tells us at the beginning of his epilogue that there is more than just a single, all-American story of World Vision. Internationalization resulted in dozens of World Visions (plural). Buried in King’s narrative and index are clues to some of these other narratives. It’s now incumbent upon other historians to follow up on Korean K.C. Han, Chinese-Filipino Jimmy Yen, Indian Jayakumar Christian, and Sri Lankan B.E. Fernando. It’s going to be a challenge that requires languages and travel. But perhaps what I first understood as a tragic shuttering of World Vision’s archives in Monrovia will in fact spur scholars to pursue compelling new international directions.