Little Falls, Minnesota is such a sleepy town that it bills itself as the place “Where the Mississippi Pauses.” But when the 20th century began, it was such a bustling center for lumber milling and farming that its population had increased by a factor of ten in just a decade. Two of Little Falls’ leading citizens were a lawyer named C.A. Lindbergh, soon to be elected to the U.S. Congress, and his second wife, Evangeline Land Lindbergh, who had come from Detroit to serve as the town’s new science teacher. Both had been educated at the University of Michigan, and their personal library reflected ample intellectual curiosity, covering not just science and law, but history, language, politics, philosophy, and religion.

Of course, we know this only because their only child (born in 1902) went on to lead such a famous life that the Minnesota Historical Society preserved the Lindberghs’ home as a historic site. Most of its materials that would interest any biographer of Charles A. Lindbergh have been moved to the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul. But Evangeline and C.A.’s books remain in the drawing room, so late last month, the site director was kind enough to let me spend a morning perusing that library.

I’m still deciding how much — or, likely, little — his parents’ reading materials indirectly shaped their son. But that library gives a window into an intellectual world that bears more than a passing resemblance to the one Charles Lindbergh would explore in adulthood.

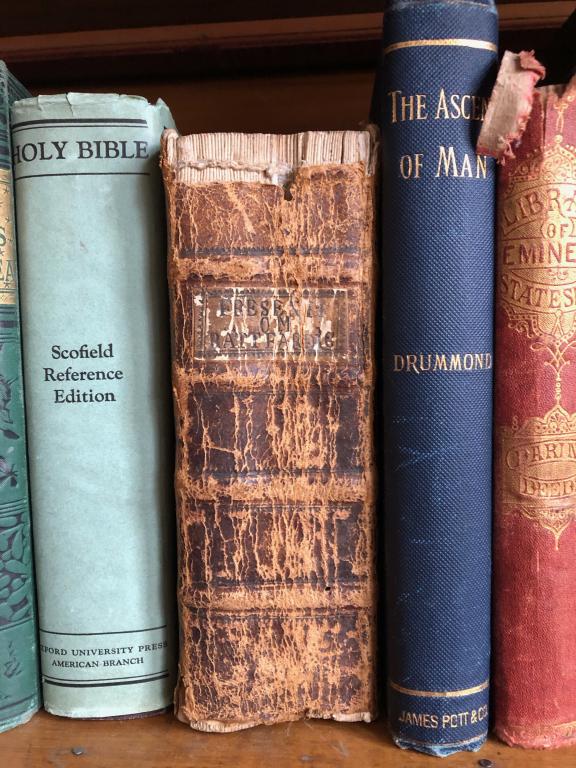

The first thing that stands out — at least, to the prospective author of a “spiritual, but not religious biography” of their son — is that the Lindberghs owned several Christian books:

• I counted five Bibles in their library, from Swedish scriptures that presumably belonged to Lindbergh’s immigrant grandparents to that standard text of dispensationalism, the Scofield Reference Bible. Most seem to have been passed down in Evangeline’s family, including an English translation of the Polyglot Bible that her preacher grandfather inscribed to her mother, “Study it daily & prayerfully.”

• Evangeline’s family collection also includes a copy of Alexander Cruden’s biblical concordance and Puritan minister John Flavel’s Christ Knocking at the Door of Sinner’s Hearts, while C.A. inherited Frederik Hammerich’s 1878 church history and a Swedish translation of a 1763 book by German Lutheran theologian Johan Friedrich Fresenius.

• As a nineteen-year old, Evangeline had received a copy of the Christian critic John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies, perhaps from a family member who worried that her college education would make Evangeline neglect what Victorians like Ruskin saw as the natural duties of women in the domestic sphere.

• It’s likely she purchased for Charles several installments of Elbert Hubbard’s series of short biographies, Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great, including one on the abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher.

• Finally, it’s not clear which of the Lindberghs (who separated while Charles was a young boy) owned Ellen G. White’s Adventist text, The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan (1911), or The Church and Modern Society (1903), a two-volume set of addresses by John Ireland, the Catholic archbishop of St. Paul.

But none of those books — like most of the Christian works in the Lindbergh family collection — seems to have been read, judging by the lack of notations, dog-ears, tears, smudges, or any other evidence of even casual use. That stands in marked contrast to some other books in the library….

Far outnumbering the Lindberghs’ Bibles and volumes on theology and church history are books by more skeptical thinkers, such as Friedrich Schiller and Thomas Huxley. The latter set including Huxley’s biography of David Hume, whose Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding Evangeline had purchased and read after coming to Little Falls. It came from the same series as one of her two books by Immanuel Kant, an edition of his Prolegomena edited by Paul Carus (a self-professed “atheist who loved God”).

But as far as I can tell, C.A. and Evangeline’s libraries overlapped in the case of just one British author who straddled the line between science and religion: Henry Drummond.

If he lives on at all in modern memory, it’s as the namesake for the Clarence Darrow character in the Scopes Trial play, Inherit the Wind. But while the original Henry Drummond did defend the evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin, he was also an evangelist for Scotland’s Free Church and an associate of Dwight L. Moody. In 1893 he was called “the foremost living member of that group of writers which may be generally be called the reconcilers of science and religion.”

So claimed the American publisher of his 1892 lectures at Boston Institute, which came into Evangeline Land Lindbergh’s possession as a book entitled The Evolution of Man. The publisher’s preface continued by lamenting how religious conservatives quoted

Text after text… from the Bible to prove that Science must be wrong. Then the Reconciler steps in to show that Scripture, properly interpreted, does not mean what the dogmatists asserted….

Of course his [Drummond’s] attitude has dismayed many of his more conservative brethren. Evangelicals did not at once know how to take him… But a large proportion of thoughtful, conscientious and earnest Christians, wavering in their faith because of the new light which science had thrown upon religion, have given an eager welcome to his teachers and have found in them the solution of their doubts.

It’s not clear that Evangeline Lindbergh actually read those lectures, but her husband took extensive notes on two other books by Henry Drummond — both of which would have appealed strongly to the Lindberghs’ son.

While it’s clear that C.A. Lindbergh read Charles Darwin’s Origins of the Species, it doesn’t seem that he encountered The Descent of Man. Instead, one of the most annotated books in his library is Drummond’s The Ascent of Man (another set of lectures, published in 1894). “If the theological mind be called upon to make this expansion [to embrace evolution],” began Drummond, “the scientific man must be asked to enlarge his view in another direction… The social and religious forces must no more be left outside than the forces of gravitation or of life.” At a time when Darwinians like Herbert Spencer (also represented twice in C.A.’s collection) advocated for the “survival of the fittest,” Drummond insisted that “It is only when both the Struggle for Life and the Struggle for the Life of Others are kept in view, that any scientific theory of Evolution is possible.”

He rejected the notion that evolutionary theory required its adherents to view the world as “one great battlefield heaped with the slain, an Inferno of infinite suffering, a slaughter-house resounding with the cries of a ceaseless agony.” Instead, through evolution God had “passed to” mankind a beneficent kind of “sovereignty”:

The moulding of his life and of his children’s children in measure lie with him. Through institutions of his creation, through Parliaments, Churches, Societies, Schools, he shapes the path of progress for his country and his time. The evils of the world are combated by his remedies; its passions are stayed, its wrongs redressed, its energies for good or evil directed by his hand. For unnumbered millions he opens or shuts the gates of happiness, and paves the way for misery or social health. Never before was it known and felt with the same solemn certainty that Man, within bounds which none can pass, must be his own maker and the maker of the world.

It’s evident how this would appeal to a young Progressive like C.A. Lindbergh. Drummond echoed themes from an American popularizer of Darwin, John Fiske. In The Destiny of Man, one of the three books by Fiske in his library, C.A. noted the philosopher’s warning that humans “have made more progress in intelligence than in kindness.” And the argument on the next page clearly struck a chord with a Midwestern lawyer who would join the La Follette wing of Congress’ Republican caucus:

And as in more barbarous times the hero was he who had slain his tens of thousands, so now the man who has made wealth by overreaching his neighbours is not uncommonly spoken of in terms which imply approval. Though gentlemen, moreover, no longer assail one another with knives and clubs, they still inflict wounds with cruel words and sneers. Though the free-thinker is no longer chained to a stake and burned, people still tell lies about him, and do their best to starve him by hurting his reputation. The virtues of forbearance and self-control are still in a very rudimentary state, and of mutual helpfulness there is far too little among men.

Even if I can’t connect this part of his father’s library with Charles Lindbergh’s oft-stated desire to improve the “quality of life,” I’ll surely be tempted to draw a different line back to the second Henry Drummond book in the library of Lindbergh père: Natural Law in the Spiritual World (1884). Its attempt to probe connections between the spiritual and physical worlds anticipates the younger Lindbergh’s later interest in a panentheistic “life stream.” And I’m sure Charles would have joined his father in highlighting Drummond’s closing critique of “the parasitic habit [of] Going to Church.” Not that Drummond opposed religious practice in its own right, but he disdained the clergy-controlled “formalism [that] cuts off individual devotion and search for truth.”

In the end, Drummond predicted that a “formal religion can never hold its own in the nineteenth century… We must either give up Parasitism or our sons.” But in the Lindbergh family, C.A. and Evangeline’s son followed them in preferring spiritual questioning to religious adherence.