Many hymns have unlikely origin stories. But I’m only aware of one that was born of the death of a fictional child. And before I even reach that tale, we need to start with a financial crisis…

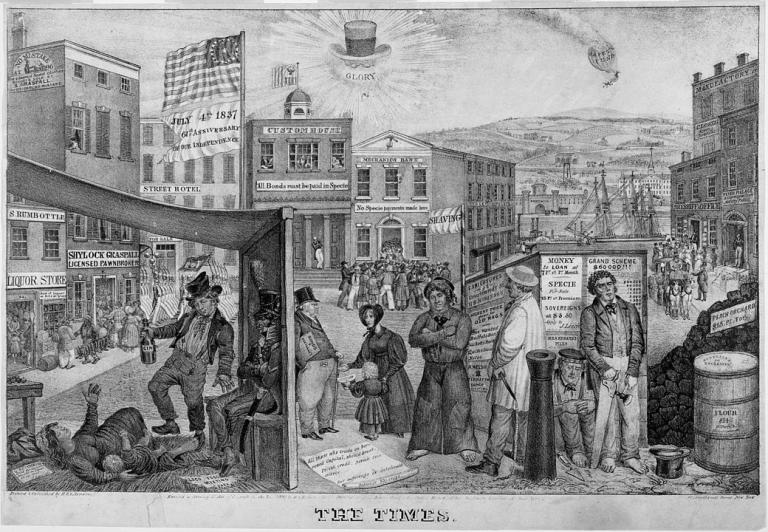

Two months into the presidency of Martin Van Buren, the Panic of 1837 shattered confidence in American banks. One victim of the crisis was a prosperous attorney named Henry Warner, who lost most of his legal business and had to sell his fashionable house in Manhattan. To help the family make ends meet, his daughters Susan and Anna began to sell novels and short stories, often foregoing royalties in order to take lump sum payments.

Writing as Elizabeth Wetherell, Susan Warner burst onto the literary scene in 1849 with The Wide, Wide World, about a young woman whose family suffers declining fortunes after her lawyer father lost an important case. Staggered by misfortune and oppressed by male authority figures (“You are mine,” her uncle tells her coldly, “You shall do just what pleases me in every thing”), Susan’s protagonist learns to trust in God and practice Christian love in the midst of adversity.

The story bore more than a passing resemblance to the Warners’ own experience, as the family found comfort in their Presbyterian faith. “[T]here was never a time,” Anna later wrote of Susan, “when my sister was not a through and through believer in the Bible.” They heard sermons by the New School revivalist Thomas Harvey Skinner and learned hymns like Joseph Grigg’s “Behold the Saviour at thy door! / He gently knocks, has knocked before.” Of her sister and herself, Anna Warner wrote, “In two hearts there, at least, [Jesus] was welcome, and two set wide the door, as well as they knew how. And the allegiance thus sworn, was never broken.”

During the winter of 1859, the two sisters collaborated on a novel for the first time. Say and Seal tells of the spiritual growth of a New England girl named Faith (really), who comes under the influence of a man named John Endecott Linden. “I don’t understand exactly what makes a Christian,” she confesses early on, “and I want to be one.”

“A Christian,” he tells her, “is one, who trusting in Christ as his only Saviour, thenceforth obeys him as his only King.”

“I don’t understand about the trusting,” Faith replies. But she learns to trust Jesus as she assists Linden with his Sunday school.

Say and Seal came out in 1860, and didn’t sell particularly well. “God knows best—and I am happy in him,” Susan insisted to her diary. But she knew that her family had to “be economical too, to make our funds last till we can get another book out. A little mortified that ‘Say and Seal’ should not have done greater things… But I am happy—and hope by faith to be happier.”

Unloved in its own time and unremembered today, Say and Seal is mawkish and moralistic. But one small piece of the novel was destined for “greater things.”

In the story’s second volume (“The book is really of very moderate limits,” the Warners prefaced Say and Seal, “considering that two women had to have their say in it”), Linden and Faith care for a Sunday school student named Johnny Fax, dying of a terminal illness. (“We were permitted to shew him the way at first,” Linden tells Faith as Johnny nears death, “but he is shewing it to us now!”) As Johnny’s life flickers, Faith watches Linden carry the unfortunate child around a room, quietly reassuring him:

She could tell how it wrought from the quieter, unbent muscles—from the words which by degrees Johnny began to speak. But after a while, one of these words was, “Sing.”—Mr. Linden did not stay his walk, but though his tone was almost as low as his foot-steps, Faith heard every word.

“Jesus loves me—this I know,

For the Bible tells me so:

Little ones to him belong,—

They are weak, but he is strong…”

Most of the novel was the work of Susan, but Anna’s contributions included those simple lines, the first two of which may have been Karl Barth’s favorite summary of the Christian faith.

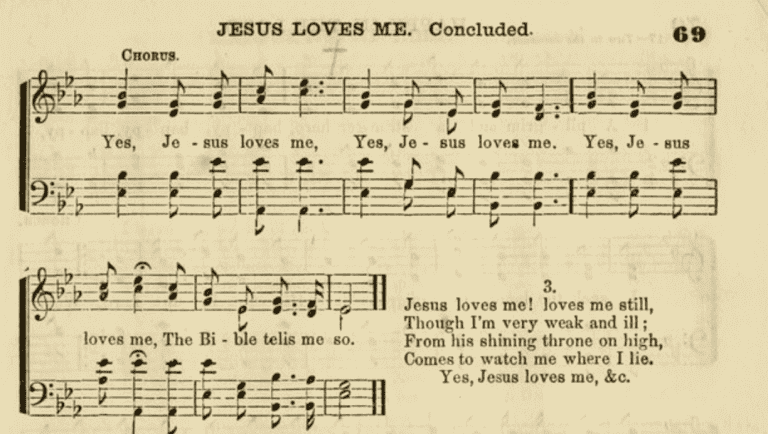

Reprinted in 1861 as part of a hymn book for the mission school of New York’s Madison Square Presbyterian Church, “Jesus Loves Me” first appeared with William Bradbury’s familiar tune the following year. He published it with a note from a Sunday school teacher who had requested a “good tune” for a hymn that was otherwise

a perfect charm. I have never known a hymn which so completely captivates the children. Boys who at first did all they could to break up our evening meetings, now venture inside, and CANNOT HELP joining us when we repeat those precious words, “Jesus loves me.”

It took only a few years for “Jesus Loves Me” to start appearing in adult collections like William Salter’s Church Hymn Book (1867) — right before one of Isaac Watts’ most enduring works. That same year, a Methodist publisher included Anna Warner’s work in a “collection of hymns and tunes popular during the last one hundred years.”

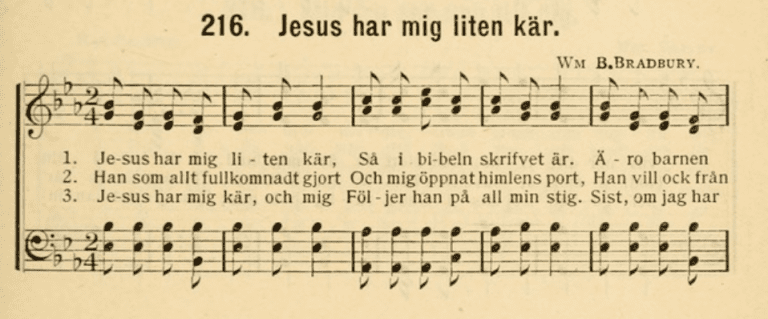

But seven years later, “Jesus Loves Me” wasn’t in the Hymnal of the Methodist Episcopal Church. (MEC North, that is. Nor was it in the southern wing’s version a few years later.) As far as I can tell from what’s indexed at Hymnary.org, Warner’s hymn didn’t show up in a denominational hymnal until 1891, when it was selected for the Hymn Book of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. Interestingly, one of the first white denominations to adopt it was the immigrant Baptist group that founded the university where I work; the Swedish Baptist General Conference included a translation of Warner’s text in 1903’s Nya Psalmisten.

Meanwhile, the country’s leading mainline groups continued to reserve “Jesus Loves Me” for children’s publications, befitting its origins in the story of a child’s death. It had been in Episcopalian Sunday school publications since at least 1874, but the Episcopal Church has yet to include “Jesus Loves Me” in its Hymnal (as of its 1982 edition, or the 1997 supplement, Wonder, Love, and Praise). I don’t think it entered the leading Presbyterian hymnal until 1990 — and then only with Warner’s first and third verses.

The Presbyterian Hymnal and its 2013 successor were somewhat unusual in omitting Warner’s generally familiar second verse: “Jesus loves me,—he who died / Heaven’s gate to open wide; / He will wash away my sin, / Let his little child come in.” But even more evangelical collections sometimes leave out her third verse, which most clearly evokes the hymn’s now-forgotten, tear-jerking source material:

Jesus loves me—loves me still,

Though I’m very weak and ill;

From his shining throne on high

Comes to watch me where I lie.