Nathaniel Hawthorne and Arthur Miller firmly tethered puritan to hypocrisy, self-righteousness, prudery, and the irrational execution of alleged witches. The term still resonates. It is easy for critics to apply the label puritan to evangelicals or Catholics who want to ban pornography. And it’s also common for conservatives to use the same label against progressive politicians and administrators. Many people want purer communities and a purer society, but nobody wants to be called a puritan.

Nathaniel Hawthorne and Arthur Miller firmly tethered puritan to hypocrisy, self-righteousness, prudery, and the irrational execution of alleged witches. The term still resonates. It is easy for critics to apply the label puritan to evangelicals or Catholics who want to ban pornography. And it’s also common for conservatives to use the same label against progressive politicians and administrators. Many people want purer communities and a purer society, but nobody wants to be called a puritan.

Does anyone want to know more about those Protestants called puritans four centuries ago? If you do, you’re in luck. Over the past year, two excellent general treatments have hit the shelves, first Michael Winship’s Hot Protestants and more recently David Hall’s The Puritans. They are both first-rate histories. Let me point you to some similarities and differences.

Almost three decades ago, Stephen Foster published The Long Argument, a long book about how developments in English puritanism shaped migration to New England and the religious culture of the region’s colonies. Both Winship and Hall offer a more sustained transatlantic approach to puritanism. Rather than starting with England and ending in America, they detail events in England and then move back and forth across the Atlantic.

Also, while Winship’s tone is snappier at times, neither author has much patience with uninformed anti-puritan snark. And nearly a century after the first academic revival of American interest in puritanism, both want to revive us again, so to speak. Winship’s opening argument for puritan accomplishments is arresting: between the 1540s and 1690, “puritans executed a king, helped remove another one, founded a short-lived republic in England, and established quasi-republics in New England … puritans reshaped England’s religious culture, destroyed much of its great medieval artistic legacy, wrote creeds and catechisms with worldwide impact, and created a lasting body of religious literature.” Not bad, especially if one doesn’t like kings or artwork. Winship repeatedly reminds his readers that a modest number of twenty-first century Protestants still appreciate the books authored by his subjects. Hall makes that same observation. Furthermore, as was true in his A Reforming People, Hall observes that despite their reputation for cruelty and intolerance, puritans placed a high value on equity and community. He praises scholarship that “has underscored the vitality of Puritan-style politics and social ethics at a moment in our national history when democracy is failing and a social ethics of ‘community’ is being jeopardized.”

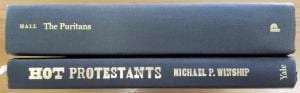

Onto some differences… Most obvious is the length.  If you put the two books next to each other, you can see that Hall’s is about twice as long. If you open them up, you’ll see that Hall’s font is much smaller as well. If you are a university instructor, don’t hesitate to assign Hot Protestants to undergrads. The Puritans, however, is a great choice for graduate students.

If you put the two books next to each other, you can see that Hall’s is about twice as long. If you open them up, you’ll see that Hall’s font is much smaller as well. If you are a university instructor, don’t hesitate to assign Hot Protestants to undergrads. The Puritans, however, is a great choice for graduate students.

Now more substantive differences. While Winship contents himself with occasional references to developments in Scotland, Hall includes Scottish Protestants as a major part of his story, devoting one full chapter (out of eight) and portions of others to the kirk. “Treating the two reformations side by side,” Hall explains, “sharpens our understanding of the politics that united the advocates of reform in England with their counterparts in Scotland or, as also happened, pulled them apart.” Scottish theologians, he continues, “were virtually unique in upholding a jure divino (mandated by divine law) system of church government alongside ‘magisterial’ (state sustained) Protestantism.” Hall’s approach also makes for a richer understanding of the events of the mid-1640s, when Scottish representatives to Parliament and the Westminster Assembly found common ground with their English counterparts elusive.

Second, for Winship separatism is part of the warp and woof of the story of English puritanism. Hall certainly pays attention to separatists, including the Leideners who were the majority of Mayflower passengers. At one point, he refers to them as “a different kind of Puritan.” When, a few pages later, he writes that “continuities can tempt us to embrace the Separatists as authentically puritan,” he implies that they were Protestants whose radicalism took them beyond puritanism. Semantics aside, though Winship repeats the argument he made in Godly Republicanism that the Plymouth (New England) church exerted a significant influence on those in Massachusetts Bay. Hall rejects the argument. I side with Winship in my forthcoming They Knew They Were Pilgrims.

Finally, Hall ends his narrative with the Restoration, marking the end of a puritan revolution in which puritans could not agree on what should replace the episcopal church government they had dismantled. Winship pushes on for several more decades, ending his narrative with the Salem Witch Trials that came on the heels of the royal reorganization of the New England colonies. The loss of self-government signaled the end of serious puritan ambitions to dominate the religious cultures of England and New England in particular. As Hall notes at the outset of his book, puritans inherited from Reformed Protestants in Geneva and elsewhere “the ambition to become the state-endorsed version of Christianity in England and Scotland.” They determined to defend “true religion against its enemies” and – here is where separatists only sometimes fit into the story – believed that kings or magistrates should use the powers of state on its behalf. After the Restoration and especially after the Glorious Revolution, puritan-style Reformed Protestants were no longer in a strong position to pursue their broader ambitions.

Hall devotes two meaty chapters to “Practical  Divinity” and “A Reformation of Manners,” two subjects at the heart of puritanism. Indeed, these chapters put puritans within the mainstream of English Protestantism. In particular, offers very incisive analysis of the “golden chain” (the phrase is from a book by William Perkins), the stages of human salvation as puritans came to understand them. For puritans, “conversion was a lifelong process,” not “a shattering rebirth.” Hence the enormous importance of the churchly means that customarily brought individuals to repentance and then to faith and assurance.

Divinity” and “A Reformation of Manners,” two subjects at the heart of puritanism. Indeed, these chapters put puritans within the mainstream of English Protestantism. In particular, offers very incisive analysis of the “golden chain” (the phrase is from a book by William Perkins), the stages of human salvation as puritans came to understand them. For puritans, “conversion was a lifelong process,” not “a shattering rebirth.” Hence the enormous importance of the churchly means that customarily brought individuals to repentance and then to faith and assurance.

It is worth noting that although puritanism became synonymous with intolerance and persecution (Winship terms his subjects “the most aggressively intolerant defenders of England’s fledgling Protestantism”), they were hardly islands of intolerance in a sea of religious toleration. Especially until the Civil Wars of the 1640s, the chief argument among English Protestants was not whether or not there should be only one religious option, but what that option should be. Many people associated the New England puritans with Salem (which Winship terms a “horrific fluke”) and, if somewhat less well known, persecution of Quakers and Baptists. This reputation for intolerance is well deserved if Rhode Island is the benchmark, less so if one makes comparison with Laudian England or even Restoration England, in which scores of Quakers died in prison.

“Is there really no means of appropriating the Puritan movement for our own times?” Hall asks in closing, noting that only a handful of evangelical scholars appreciate “the richness of Puritan spirituality.” I don’t think many other Americans will make the sorts of appropriation that Hall endorses, but that’s no reason for historians and Christians to avoid a careful reexamination of the most significant religious impulse in the trans-Atlantic English world of the seventeenth century.