It’s not the kind of headline you hope to see in the Chronicle of Higher Education, but there it was earlier this month: “Will your college close?”

Writers Robert Zemsky, Susan Shaman, and Susan Campbell Baldridge hastened to reassure readers that “Closings will not be nearly as prevalent as some prognosticators have predicted.” Based on a market stress test they developed, Zemsky, Shaman, and Baldridge estimate that 60% of America’s thousands of colleges and universities “face little to no risk” of closing anytime soon. But 30% “are likely to struggle,” and one in 10 is expected to simply cease operations.

As a college professor, I can’t say I like those odds. But as a historian, I need to acknowledge that college failure is a regular theme throughout the history of American higher education. What we face is not without precedent, though a 10% closure rate would be significantly higher than what higher ed has experienced in its modern era. To explain, let me briefly revisit and update a 2013 series from my own blog.

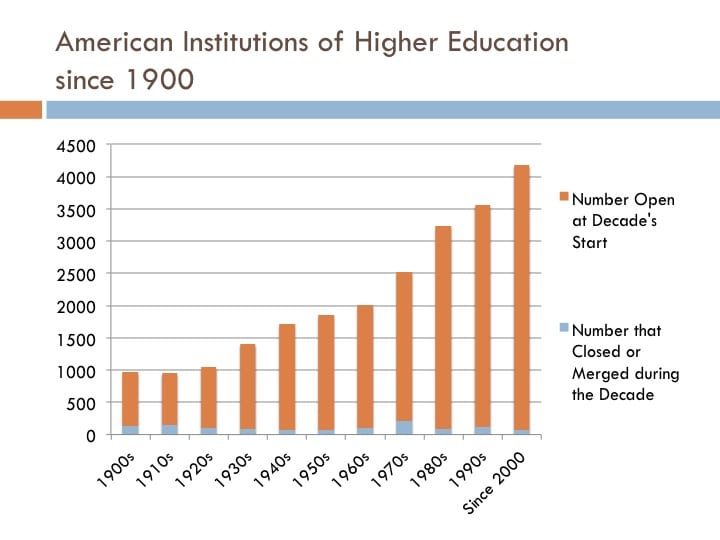

Using data collected by Ray Brown, former institutional research director at Westminster College (MO), I considered just how common it was for colleges, universities, seminaries, and other postsecondary institutions in the United States to close. Here’s the graph I posted in 2013, showing closures decade-by-decade as a share of the overall number open at the start of each period.

Seven years ago, I could start my analysis of that data on a (relatively) optimistic note, emphasizing “that it’s a relatively rare thing for a college, university, seminary, law school, or other institution of higher learning to close in the 20th and (so far) 21st centuries. Moreover, [those] 1200+ closures and mergers have done little to slow the expansion of higher education since 1900.” With the exception of one such period, over 95% of colleges open at the start of each decade between 1940 and 2000 remained open ten years later.

Then there was the 1970s, when the closure rate spiked over 8%. In part that was because some niche categories—teacher’s colleges, women’s colleges, independent medical and nursing schools—saw a rash of closures and mergers, to the point that they were rendered obsolete, or very nearly so. (And the single-sex colleges that survived have been among the first to risk closure in more recent years.) Other institutions that failed in the 1970s had been founded in the midst of the flush times after WWII, when financial aid became much more readily available to a postwar generation, and never secured the stable finances that would let them survive the economic challenges of the Seventies. Indeed, 36% of the institutions that closed between 1950 and 1979 had been established after 1945.

But ominously, I found that virtually the same percentage (37%) of institutions that had closed since 1980 had been open since before 1910. “Now, none of these is especially well-known outside of its region, alumni group, etc.,” I wrote, too dismissively. “But for those of us who work at private four-year colleges, it is unsettling to see how many long-lived schools of that type have expired of late, most even before the Great Recession and explosion of MOOCs got talk of a burst bubble bubbling.” Those “massive open online courses” turned out not to be the disruptive innovation that some desired or feared. But looking back with seven years of hindsight, it seems obvious that the bubble is leaking air, if not bursting.

What happens if you apply my 2013 method to the decade that just finished? How many American institutions of higher learning survived the 2010s? According to Ray Brown’s ever-lengthening list, 208 closed or were absorbed in mergers between 2010 and 2019 — out of 4,634 that the Chronicle reported for 2010.

That closure rate of 4.5% would be the highest (by my admittedly rough method) for any decade since the Seventies. And it seems to be accelerating: when I first did this exercise, only 1.6% of the schools open in 2000 had closed by 2013.

Now, more than half of the closures in the 2010s came in the for-profit sector, which has less regulation (and vastly higher student debt) than the non-profits. And we’re still not even halfway to the 10% closure rate suggested in this month’s Chronicle article.

But a recent series of closures suggests the pace is quickening, and that my particular sector of higher ed may face unique challenges.

I’m not sure if institutions like my employer are at greater risk than others. You don’t have to have a religious identity and mission to be nervous about being an expensive, tuition-dependent, low-endowment institution that needs to keep raising its discount rate to attract a shrinking pool of students from an overcrowded regional marketplace.

But having a distinctively Christian mission — much as I might value it — certainly doesn’t protect a school from the risk of closure. Just consider some very recent history:

- Of the 10 non-profit schools on Brown’s list that closed in 2019, half had church connections: Baptist Seminary in Richmond, Hiwassee College, and three small Catholic schools (Marygrove, New Rochelle, and St. Joseph).

- Faced with the loss of its accreditation, Cincinnati Christian University closed as 2019 turned to 2020.

- Earlier this month, theologian Myles Werntz shared on Twitter that his employer, Logsdon Seminary of Hardin-Simmons University, would be closing after the 2020-2021 year. (Later in the month, Hardin-Simmons itself eliminated programs and faculty and staff positions.)

- A couple days after Werntz’s post, Concordia University in Portland, Oregon abruptly announced its board’s decision to close the school this May, prompting a class action lawsuit by students who say they would not have come back for the spring semester had they known it was to be the school’s last.

Like most of our contributors’ employers, Concordia is a member of the Lilly Network of Church-Related Colleges and Universities. While small colleges have been the most likely to close so far, Concordia’s Portland campus is home to 1,800 undergraduate and graduate students (plus thousands more in online programs), large enough to make me less certain that a well-established Christian college like Bethel is “too big to fail.”

In fact, it’s possible that religion adds extra layers of “market stress” that won’t be captured by Zemsky, Shaman, and Baldridge’s method.

In fact, it’s possible that religion adds extra layers of “market stress” that won’t be captured by Zemsky, Shaman, and Baldridge’s method.

First, in a time when higher ed is increasingly expected to respond to the needs of the market, Christian colleges (necessarily) have a complicated relationship with the economy. A recent Cardus study confirmed that alumni of private religious colleges earn lower salaries than their public and private nonreligious peers — perhaps because they’re more likely than other college graduates to define their calling in terms of helping others and somewhat less likely to emphasize making money. That seems to accord with the assumption that fundraising at my institution tends to lag behind its competitors because so many of our alumni labor in relatively underpaid professions like teaching, nursing, ministry, and social work. In an economy that continues to squeeze the middle class, will such Christian college alumni be able to donate to their alma maters, or to afford private college tuition for their own children?

Of course, religious colleges do churn out alumni who enter lucrative careers and become major givers. More and more of our students are pursuing high-paying careers in business, engineering, scientific research, and medicine. And universities like Bethel are working as hard as their non-religious competitors to forge partnerships with corporations and other employers. But there’s an inherent tension. Much as a school like Bethel depends on attracting the resources of those who benefit most from our economy, its religious and educational mission as a Christian liberal arts college demands that our faculty and students ask hard questions about the inequalities and injustices of that same economy.

And that’s not the only kind of tension that may complicate the future of religious schools. No doubt enrollment and fiscal issues did much to doom Concordia-Portland and Logsdon Seminary. But there may have been other reasons, more particular to the institutions’ religious affiliations. In the case of Logsdon, Baptist News Global reported that “a small but influential group of individuals has been working behind the scenes to convince trustees that the school aligned with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship is too liberal to be trusted in today’s Baptist General Convention of Texas.” And The Oregonian reported that the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod tied financial support to Concordia hewing more closely to the conservative denomination’s stance on gender and sexuality.

At one time, having ties to a denomination or other well-defined religious constituency might have helped a private college or seminary to weather an economic downturn, since it could count on recruiting and fundraising from an affinity group with strong loyalty to the institution. But schools like mine now receive hardly any money from their sponsoring denominations, whose individual members feel increasingly comfortable sending their children and donations to (and hiring their pastors from) a wider array of educational alternatives.

Yet the denomination can still feel entitled to police the religious boundaries of the college or seminary. And as the reporting on Concordia-Portland and Logsdon suggests, denominational leaders — or a smaller subset of conservative constituents — might even use the present economic urgency as leverage: stop “trending left,” or else.

As it happens, Bethel is going to announce a new president this Thursday morning — two months before it announces the elimination of up to 30 faculty positions. I can only hope that our search committee has selected someone who will make it possible for the professors who remain to keep doing everything that I extolled in my open letter about Christian higher ed. Because if our new president isn’t someone who combines forward-thinking vision with an abiding commitment to the mission of the Christian liberal arts, and if she isn’t someone who spends more time expanding our pool of families and donors than assuaging the unfounded religious anxieties of a shrinking base, then it’s possible that her chief legacy will be to preside over yet another Christian college closure.