Dear Christian parents,

There are few decisions that inspire more hope and fear than your children’s choice of where to go to college. Some of you have kids facing that decision in the next weeks or months, as high school seniors sort through acceptance letters and financial aid offers. But even if you have kids as young as my 10-year old twins, it’s hard not to worry what will happen when the people you love most in the world leave home to start an intensive experience that will do so much to shape their work, their relationships, and their values and beliefs.

So I don’t doubt that some of you resonate with the concerns articulated by Southern Baptist scholar Denny Burk in a recent thread on Twitter:

CHRISTIAN PARENT:

There is hardly anything more destructive you can do to child’s faith than to send him to a “Christian” college/university that is theologically liberal, trending left, or only nominally Christian.

/1

— Denny Burk (@DennyBurk) December 27, 2019

Now, some of you have no idea what Burk is talking about. Though his tweets are ostensibly addressed to any “CHRISTIAN PARENT,” he’s really speaking to that relatively small subset of Christ-followers standing on his side of a theological “line in the sand” (to use a favorite phrase of his).

Some of you are Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians whose children are considering religious institutions that Burk would dismiss as “nominally Christian” colleges. For example, your kids might have applied to schools that maintain relationships with Christian denominations, but don’t expect their faculty to affirm the beliefs of those churches. (In fact, those schools might hire non-Christian faculty because they believe that all truth is God’s truth, or because they see it as a way of loving their neighbors and welcoming the stranger.) Many of my family and friends attended such colleges, and most had their Christian faith deepened by the experience.

But some of you are fellow evangelicals or other kinds of theologically conservative Christians who want your children to attend a different kind of Christian institution of higher learning: one that requires its faculty to affirm particular Christian doctrines, requires its students to take Christian theology and Bible courses, and strives to integrate Christian faith, learning, and living in all that it does.

One like my workplace: Bethel, a Christian university in suburban St. Paul, Minnesota.

Or is it actually “Christian”?

It seems that Burk wants you to ask that question. He doesn’t name Bethel in particular, or any other college or university that is supposedly “trending left.” But because he doesn’t point to any particular cases, he neither justifies his concerns nor limits the extent of the doubt they may foster. You might read his tweets and wonder if Bethel faculty like me really affirm the faith statement we have signed, if we really meant the Christian testimonies and meditations that we wrote in being hired, tenured, and promoted.

Of course, no single person or tweet created such doubts. Rumors of “liberal drift” have simmered throughout my seventeen years at Bethel, and occasionally reached a boil. And that’s nothing new. One of Tal’s books quotes an 18th century student saying about the German university that is one of Bethel’s educational and spiritual ancestors: “So you’re going to Halle? You’ll return either a pietist or an atheist.”

I don’t know anyone at Bethel who doesn’t want our students to follow Christ as he is attested in Scripture. But one legacy of Halle’s Pietism is the evangelical conviction that authentic Christianity cannot result from coercion or conformity, only choice. So at Bethel, we believe that our students must encounter multiple points of view and be as free to reject faith as to affirm it.

Inevitably, a Christian university of that type will seem “Christian” to some other believers and a “university” to some other educators. But it’s the kind of institution to which I’ve dedicated my career.

So how do you know that a Christian university like Bethel is the right option for your child? How do you assuage concerns like Burk’s?

First, don’t just listen to what someone on the Internet says. (Myself included.) Don’t put credence in whispered rumors about something as amorphous as “drift.” Do your due diligence and talk in concrete terms to someone who can actually address the concerns: not an alumnus or even an admissions counselor, but someone who currently teaches at the college or university your child is considering. Better yet, talk to two professors — one who teaches in your child’s likely major field of study, then another who teaches in the general education curriculum that all students share — and perhaps also to someone who works on the co-curricular side, like a coach, campus pastor, or resident director. They’ll all give you different perspectives on the experiences that will do most to define your child’s education.

Again, I’m several years away from going through this process myself. But there are two questions I would make sure to ask.

What difference does your Christian belief make in your work?

If you really wonder about a professor’s agreement with some particular plank in a doctrinal statement, ask her about it. But as a Pietist, I wouldn’t put too much stock in intellectual assent. Instead, I’d want to know how that belief inspires or shapes her teaching, or some other dimension of her calling as a professor. For example, does her belief in the bodily resurrection of Jesus (part of article 4 in the affirmation we sign at Bethel) help her overcome her fears and inspire her to teach, mentor, research, and write out of “a living hope” (1 Pet 1:3)?

As you start talking about the difference that lived faith means in an educational context, you’re ready to have the conversation that’s most meaningful to your child’s experience. Now you might get meaningful glimpses into what Bethel’s longest-serving, most famously pietistic president said is the actual core of education at such a college. “We believe,” affirmed Carl Lundquist, “that in the end the impact of one life upon another is probably greater than the impact of an idea…”

(By the way, the fact that I keep talking about Bethel and Pietism should underscore that there’s no such thing as a generically Christian college. All such institutions have distinct roots, influences, and commitments. So if you’re looking at a school like Baylor, talk to someone like Beth about Baptist views of higher education. Or at David’s school, ask about Wesleyan education, or Reformed views at Kristin’s. On to the second question for the professor you interview…)

How will you challenge and support my child in her walk with Christ?

If the goal is for students to choose to follow Jesus, and not simply to imitate their parents’ practice or repeat their pastors’ words, then they need to be challenged and supported in making their faith their own.

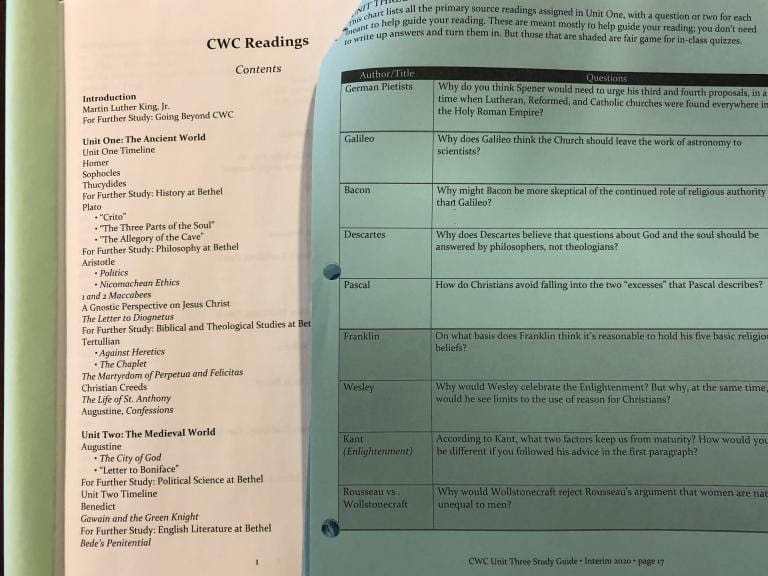

Yesterday we opened the “J-term” version of Bethel’s foundational first-year course on Christianity and Western Culture. “This might be the most difficult thing you do all year,” I warned our students. Not just because they need to comprehend two millennia’s worth of vocabulary, chronology, and geography, all crammed into a three-week immersive experience. That’s hard, but the real challenge comes as we prompt our students to ask some of the most profound questions humans can ask: Who am I, and who should I be? What is the good life? What is truth, or justice? What values do I hold, and how have they been shaped by my culture? How do I answer any of these questions? On what basis?

If that’s not hard enough, we don’t just give them a Christian answer to each question, but an array of Christian — and non-Christian — responses, all rooted in particular historical contexts that change over time.

And I’m sure my colleagues in the sciences, the arts, and our professional programs would tell you about challenges of a different kind but similar difficulty. It’s what produces the transformational education we promise. Such learning experiences, wrote the American Pietist educator Karl Olsson, “end in a mood of fear and trembling.” They must be so, for “no student ever matures who has not felt the earth shaking beneath his feet.”

But at the same time, Olsson continued, the ideal Christian college professor “will see his student as a person and will be a steady, firm, but gentle midwife of the soul.” So we almost never talk about challenge at Bethel without soon turning to support.

It doesn’t mean that you should expect us to tell your child what to think. But you should expect us to equip her to ask and answer questions as well as she possibly can — and to live with the tension, paradox, and mystery that are essential to Christian faith.

You should expect that we’ll encourage her. Literally en–courage her: to face her fears — of uncertainty, of conflict, of failure — and live in hope.

You should expect that we’ll help your child to hear God’s call for her, to cultivate God’s gifts to her, and to fulfill God’s mission through her.

So may God the Father grant you wisdom as you parent your children into, during, and after their time in college. May God the Son walk with your children through every trial they might face. And may God the Spirit counsel and comfort your children in this and every choice they make.

Chris Gehrz

Professor of History

Bethel University

St. Paul, Minnesota

P.S. I generally used “her” for the pronoun in this post because more than 60% of our students are women, which is not unusual for a Christian college of Bethel’s type. But also to underscore that there’s hardly anything more destructive of our daughters’ faith than a Christian college that stifles God’s call to women, neglects God’s gifts to women, or teaches women that God doesn’t mean them to play leading roles in the ministry and mission of the church.