Look at this figure, and tell me what it is, and where it is. The first question is easy. The second is odd, to the point of being bizarre. It involves some real twists and turns, with curious international and diplomatic angles.

The statue is unquestionably the Virgin of Guadalupe, the form of the Virgin uniquely beloved in Mexico. It looks as if it came from a wayside shrine, or a church in Mexico itself, and I think it is a significant piece. As to date, seventeenth century is plausible, if not earlier, but I am wide open on this. As I’ll explain, establishing exact provenance is not really possible. By way of comparison, here is the famous original Guadalupe image:

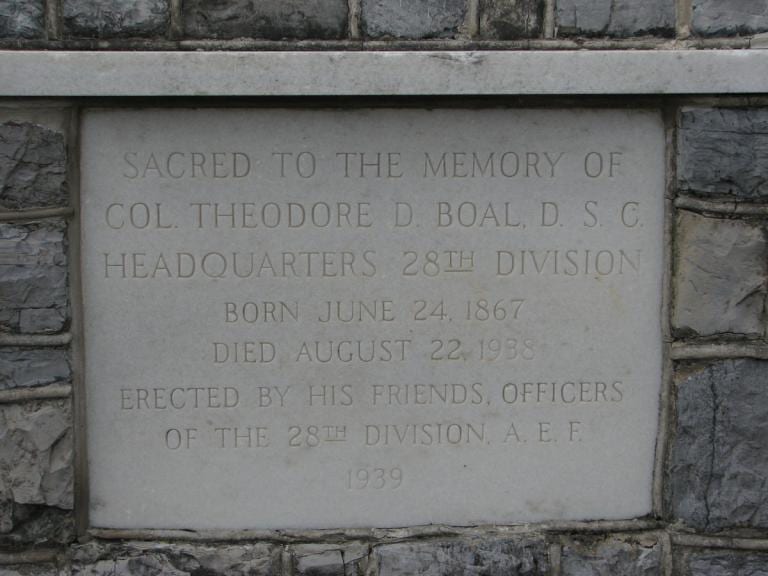

But where this particular statue can now be found is surprising indeed. It stands at the heart of a open air monument commemorating the fallen officers of the US 28th Division, at a First World War shrine attached to the Pennsylvania Military Museum in Boalsburg, PA, a few miles from State College. Historically, that is absolutely not an area with any particular Latino heritage. Nor until quite recent times was Catholicism strong in the area. In Boalsburg, as in most villages and smaller towns in the area, the obvious older churches are all Protestant, whether German (Lutheran or Reformed) or Scotch-Irish (Presbyterian or Methodist). So how did this ultra-Catholic statue get here?

I have known this statue for many years, and occasionally wondered about it. But when I started asking questions, it soon emerged that virtually nobody could supply detailed answers, and even people who knew the site well had basically no idea that the Virgin was there, or what she was. As far as I can tell, that neglect also extends to the sizable Penn State/State College Catholic community, who have never (say) organized any kind of religious event there. Put it this way: after many years of residence, I have never met anyone in the area who has so much as heard of the statue.

So here are my investigations to date, and further assistance would be greatly appreciated.

The story begins with the Boal family, firm Protestants who left Ireland at the end of the eighteenth century and settled on the then-wild frontier, founding the village of Boalsburg. One later member of the house acquired considerable wealth. This was Theodore Davis Boal (1867-1938), a prosperous architect. Theodore – “Terry” – was strongly committed to France, where he married his wife. From the late 1890s, he adopted the lifestyle of a country squire in a great house, as he expanded and reconstructed that original house in Boalsburg. Through his wife, he even inherited the chapel that had once belonged to Christopher Columbus – and which now, amazingly, stands reconstructed in Boalsburg, PA.

Anyone familiar with Northern Ireland will know the Boal name from the very important far-Right Protestant politician Desmond Boal, sometimes described as the brains behind Ian Paisley. I assume he was distant kin, which makes the Catholic aspects of the family’s US history all the more ironic.

In the early twentieth century, Theodore Boal shared the alarm of his friend and namesake, Theodore Roosevelt, about growing menaces to US national security. Accordingly, he prepared his own militia troop ready for the day when war would come. In 1916, he founded the “Boal Troop,” a mobile machine gun unit, which was then incorporated into the Pennsylvania National Guard. I take the following from Philip Sauerlender, “Boalsburg’s Rough Riders: Terry Boal and the Boal Troop,” Mansion Notes, 38.1, Centre County Historical Society, Winter 2016:

They were sent in the Fall to guard the Mexican border in Texas while Pershing chased Pancho Villa.

I originally suspected that the Guadalupe figure might have been acquired during the Boal Troop’s 1916 service on or over the Mexican border. Visions of The Wild Bunch danced before my eyes … but this turns out to be flat wrong. Back to Sauerlender:

The next year war was declared and the Boal Troop was incorporated into the 28th Division U.S. Army as part of a machine gun battalion. Theodore Boal was detached and put on the staff of the 28th Division. Both Boal and the troop served in the war where they received honors.

Theodore became a Lieutenant Colonel.

Boal returned from France with a railroad carload of military relics for a planned 28th Division Officers’ Club and Museum on his estate. The troop was reformed and stables built on the property. As part of the Officers’ Club, Boal designed and started construction of a World War Memorial. Although the Officers’ Club and cavalry troop were disbanded, the memorial was expanded and evolved into the present 28th Division Memorial and Pennsylvania Military Museum in Boalsburg.

As the shrine grew in the 1920s, it incorporated an extensive wall containing plaques commemorating officers, and in the center was a blank space intended for Boal himself when he died. This was a shrine within a shrine, which is deliberately built to look like an altar. This is the space now occupied by the Mexican Virgin.

The responsibility for filling that vacant space on the wall fell to Theodore Boal’s son Pierre de Lagarde Boal (1895-1966). As his name suggests, Pierre was born in France, and he maintained that European connection throughout his life. He married a French wife, and converted to Catholicism for the occasion. A romantic figure straight from the pages of Scott Fitzgerald, he joined the French army cavalry, the Cuirassiers, and in 1914-15 he fought with the Lafayette Flying Corps, the Lafayette Escadrille. He received a Legion of Honor citation, the Purple Heart, the Croix de la Guerre with gilt star, and the Lafayette Flying Corps ribbon. He enjoyed a distinguished diplomatic career, with a focus on Latin America. That included time in Mexico, in 1919, and again from 1936 through 1940, as Counselor to the US Embassy. He served as Envoy Extraordinary to Nicaragua (1941-42) and US Ambassador Extraordinary to Bolivia (1942-44).

To pull the story together, Theodore Boal died in August 1938, and a monument was indeed erected. In September 1940, a newspaper article reports “that Pierre Boal (attached to the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City) brought back with him a Madonna and bell he obtained in Mexico for placement above the altar.” (I owe this reference to the kindness of Military Museum educator, Mr. Joe Horvath).

So what exactly is this statue? It is certainly Mexican, but the question remains of just where that statue had come from in the first place. “Obtained” how exactly? Surely some local church did not just decide to hand a cherished item over to the wealthy gringo passing through? This is not from a parish gift shop.

Some context might be in order. In the decades following the Mexican Revolution, the Catholic church suffered severely in that country. Brutal persecutions recurred during the Cristero War of 1926-29, a horrific conflict largely forgotten by Americans, in which over a hundred thousand perished – not to mention hundreds of thousands of refugees forced to flee to the US. Mexican left-wing radicals were very repressive toward clergy and believers through the 1930s, the era made famous by Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory (1940).

Through those years, Mexico was in semi-permanent confrontations with the United States, and that made the Mexican struggles a recurrent issue in domestic US politics. The US Catholic church, and Catholic leaders, repeatedly demanded intervention against the radicals and persecutors, even to the point of advocating invasion. In 1927, the Mexican government was dreading a US invasion, and US Catholics were praying for one – although the Coolidge administration itself apparently never seriously planned for such a step. Had US forces actually decided to occupy Mexico, a detailed plan was sitting on their shelves, namely War Plan Green, which remained notionally in force until 1946.

Concern continued through the 1930. In 1932, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Acerba Animi (On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico). In the US, the demagogic Father Charles Coughlin made these Mexican horrors one of his special themes, and warned of sinister plots between Mexico and the Soviet Union. Father Michael Kenny published hair-raising books denouncing Mexican atrocities, under titles like No God Next Door – Red Rule in Mexico and Our Responsibility (1935): that book became an overnight best-seller. Cries for intervention became all the more strident in 1938 when Mexico nationalized US-owned oil resources in the country.

Weirdly, one of the main forces in the US strenuously opposing such aggressive interventionism through that whole period was that well-known body of upstanding anti-war, anti-imperialist, liberals … um, the Ku Klux Klan, who made it one of their big campaigning issues. After all, they really could not see much wrong with the thought of a secularist/Masonic government persecuting Catholics. The Klan donated money to the Mexican government to help them suppress Catholic Cristero rebels. The US Knights of Columbus tried to support those same rebels financially – while denying military aid – making it a kind of proxy war.

As a diplomat, Pierre Boal would have been in a very delicate position through these explosive years of the late 1930s. Was the statue a present to Boal from some devout Mexican Catholic family, perhaps grateful for his assistance? As I noted, his connections with the country went back decades. For what it is worth, the Cristero revolutionary slogan was “Long live Christ the King! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!” Note the Cristeros‘ Guadalupe banner here:

Or to offer a scenario that is at least as likely, it is very feasible that some local government official or warlord could simply have looted the statue from some church or shrine, and sold it to the highest bidder. A lot of church properties were plundered and desecrated in these bitter years, especially during the Cristero struggles, and many once-prized items were on the open market. It is rather like the antiquities market in the Middle East today following the wars in Iraq and Syria. As a faithful Catholic, Pierre Boal would have had nothing consciously to do with any such misappropriation, and he might have regarded buying the statue as a chance to save it from outright destruction. I am speculating.

Or assume that he simply purchased it through a dealer. So where did the dealer get it in the first place? It was assuredly not through any simple legal channels, and it had very likely been looted. Again, Pierre Boal was no wide-eyed tourist in Mexico, and he would certainly have known that.

Whatever the origins, erecting a statue like this in the particular circumstances of 1940 was a highly political statement about ongoing affairs in Mexico, although perhaps nobody watching the ceremony at Boalsburg realized this, except for Pierre Boal and his immediate family. But it also had a strong US resonance, at the exact time that Father Coughlin’s Christian Front paramilitaries were running riot in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York City (for instance), attacking Jews and leftists. Whether in Mexican politics – or US domestic affairs – the statue was even a pretty aggressive declaration, and there is no way around that. For a diplomat like Pierre Boal – well, it was pretty undiplomatic.

If anyone can suggest any further context about the statue’s date or region of manufacture, I would love to know. Does anyone know of some plausible parallels?

But here is my point. However it got there, we have a fine and rather moving statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe in the middle of rural Pennsylvania. Back in 1940, it was purely exotic, but in the modern US, with its sharply rising Latino population, it acquires a whole new relevance. If I had any say in the doings of the PA Military Museum, or of Boalsburg itself, I would draw attention to this, and try to attract visitors.

Who knows, it could yet become a regional pilgrimage shrine in the traditional sense of that word. See you there next December 12?

And I haven’t even started on the bell that Pierre brought back with him …

Next time, more about the Virgin, and some of the truly odd places that she chooses to descend.