Today The Anxious Bench welcomes Erik R. Seeman, Professor of History at the University at Buffalo. Seeman’s publications span many centuries, cultures, and topics, but several of his books analyze the beliefs and rituals that surround death and dying. One of my favorite books in the field of early American history is Seeman’s Death in the New World, which compares the deathways of Native, African, and English cultures. Below Seeman and I discuss his latest book, Speaking with the Dead in Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019)

JT: You repeatedly draw on Robert Orsi’s definition of religion as “a network of relationships between heaven and earth involving humans of all ages and many different sacred figures together.” Orsi has mostly written about Catholics. I have found his definition very useful for understanding the Latter-day Saints. Many scholars contrast Protestant “absence” and Catholic “presence.” How has that contrast hampered our understanding of Protestant religious experience?

JT: You repeatedly draw on Robert Orsi’s definition of religion as “a network of relationships between heaven and earth involving humans of all ages and many different sacred figures together.” Orsi has mostly written about Catholics. I have found his definition very useful for understanding the Latter-day Saints. Many scholars contrast Protestant “absence” and Catholic “presence.” How has that contrast hampered our understanding of Protestant religious experience?

ES: Some scholars have taken the pronouncements of Reformation ministers and theologians too much at face value. In their heated debates with Catholics, Protestant theologians articulated strong positions in favor of “absence” – that is, the lack of relationships between humans and sacred figures other than God. In particular, Reformers rejected Catholic belief in purgatory, which had allowed medieval Catholics to maintain relationships with the dead through their prayers.

The Reformers’ rejection of purgatory has led some scholars to insist that Protestantism was a religion of “absence.” As one recent history of the Reformation puts it, “Protestantism stripped religion of mediation and intimacy with the dead.”

That may have been what ministers and theologians intended – Luther and others feared that attention to the dead distracted people from God’s glory – but it certainly was not the experience of most Protestants in the centuries following the Reformation.

To be fair, I’m hardly the first scholar to see Protestantism as a religion of “presence,” even though I am among the first to phrase it that way. Many historians have written about the lively supernaturalism of Protestants in early modern Europe and North America. I think about Robert Scribner’s great work on Germany, David Hall’s pathbreaking Worlds of Wonder, Alexandra Walsham on providentialism, Doug Winiarski on the role of the Holy Spirit in the Great Awakening, and so on.

JT: In the seventeenth century, most New Englanders at least formally believed that they could not know whether their deceased loved ones were saved or damned. This included children. However, I have noticed that by the end of the seventeenth century, orthodox Congregational ministers offer assurance that infants and young children who died went to God’s presence in heaven. Could people simply not stomach the thought of children in particular as the objects of God’s wrath?

ES: This is a subject that has interested me since my first book, Pious Persuasions (1999). Here I first became aware of the importance of minding the gap between prescription and practice. Puritans’ Calvinism should have meant that even young children who died could have wound up in hell, just like adults.

When ministers wrote or preached about this topic, they could be unsparing in their Calvinist logic. “Your children,” Cotton Mather asserted, “are born children of wrath. Tis through you, that there is derived unto them the sin which exposes them to infinite wrath.” In other words: the souls of your dead children may be in hell.

But in their pastoral duties, when ministers visited the dying and the grieving, they frequently voiced a softer line and emphasized Christ’s redeeming grace. And when lay men and women wrote in their diaries about their deceased children (and, for that matter, about their deceased spouses and parents), they almost never fretted that their loved ones’ souls were in hell.

JT: Many historians are struck by the emergence of robust relationships between the living and the dead in the nineteenth century. Mormons quickly warm to baptisms for the dead. And then countless Americans participate in Spiritualist séances. You argue that such practices build on a “cult of the dead” already present within the early nineteenth century United States. What do you mean by a “cult of the dead”?

ES: This, I believe, is the book’s most important finding. Previous scholars have seen the antecedents of séance Spiritualism in several relatively marginal movements: Swedenborgianism, Shakerism, and Mesmerism. By contrast, I see Spiritualism building on a much broader cult of the dead.

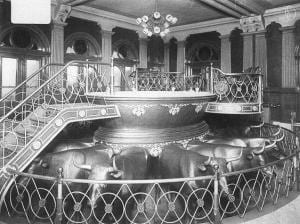

Using the definition of a “cult” as a “form or system of religious worship or veneration” directed toward “a specified figure or object,” I show that numerous antebellum Protestants venerated their deceased loved ones. Participants in the cult of the dead adhered to five tenets: 1) corpses deserved adoration, 2) the souls of the dead turned into angels, 3) souls could return to earth as guardian angels, 4) burial grounds were especially likely to hold returned spirits, and 5) praying to the dead was a legitimate form of religious communion.

These beliefs were much more widespread than the three relatively marginal movements I mentioned above. I found evidence of such beliefs in everything from diaries and letters to funeral hymns, parlor songs, gravestone epitaphs, and sentimental poetry. The frequent expression of these ideas helps explain the rapid growth of séance Spiritualism. When in 1848 the Fox Sisters said they could communicate with the dead, they found a large audience primed to accept their claim.

JT: Shakespeare’s Hamlet refers to an “undiscovered country from whose bourn / No traveller returns.” Of course, Hamlet soon found that wasn’t the case, and so have Americans across the centuries. What has changed is how Americans have understood the persistence of the dead and the ways in which the dead do or do not interact with the living. If you don’t mind getting the story up to the present very quickly, how have things changed since the mid-nineteenth century?

ES: Spiritualism peaked in the decades after the Civil War. With hundreds of thousands of young men killed in the prime of life, grieving families often turned to mediums to learn how their son or husband died and whether he was happy in heaven.

The twentieth century, however, was not so kind to the idea of maintaining relationships with the dead. Freud’s distinction between healthy and unhealthy grief came to dominate both medical and popular ideas about mourning. Healthy mourning involved detaching oneself from the deceased; pathological “melancholia” arose from an inability to detach from the dead. People were urged, in effect, to “get over it.”

But in recent years we have seen a renewed interest in maintaining connections with the dead. Therapists no longer urge detachment; sometimes they have the bereaved write letters to the deceased. People use social media to send messages to the dead, such as “I know you are looking after me up in heaven.” Even Spiritualism is finding new audiences. In 2012 Long Island Medium was the highest-rated show on cable television. It is still going strong after 14 seasons and 180 episodes.

JT: The final paragraph of Speaking with the Dead is intimate and arresting: “I don’t believe in ghosts. I don’t believe in mediums. I don’t even believe in God. So after my grandfather died, I was especially grateful for that [retained] voice mail he left. I didn’t think I was going to meet ‘The Ghost’ in heaven, so I was glad to experience the power of speaking with the dead.” It hearkens back to an anecdote about a family funeral with which you begin the book. Why did you choose to begin and end your book with your own experience?

ES: The simple answer is that I wrote the introduction and conclusion shortly after attending my grandfather’s funeral, and it was on my mind.

The longer answer is that I had been looking for something to draw readers in. The book covers 300 years and deals with some complicated theological ideas, but I wanted the narrative to be accessible enough that any undergraduate or non-academic could understand it. Not just that they could understand it, but that they would want to follow along for 270 pages. If I opened with a historiographical debate it would signal to those readers: you’re not really wanted here.

And there’s an implicit argument that emerges from my grandfather’s funeral – an argument I wasn’t quite bold enough to make explicitly in the book: that mourners universally miss the beloved departed and want to maintain connections with them.

Twenty-five years of research on death across four centuries and numerous societies has convinced me of that. I understand that historians are leery of universals. I’m leery of universals! And of course I would qualify that universality by talking about how grief and the desire for connection are expressed differently in various times and places. Absolutely. But I used my grandfather’s funeral to suggest that an atheist today and a Shaker two hundred years ago and a puritan four hundred years ago all share something deeply human: the desire to maintain a connection with the dead.