Yesterday marked the debut of a new podcast from Annie Berglund, one of my colleagues at Bethel University. Seeing Animals will have new episodes each week this spring and fall, with interviews that mirror themes from Annie’s course on animal ethics. She was kind enough to answer some of my questions about her podcast, her course, and her interest in animals.

As a historian… What’s the history of your own interest in animal ethics? Where did it start?

I’m the third child of four siblings, so the make-believe narratives of my two older sisters directed our childhood games. While Kalley and Rosie argued over the coveted roles of Ariel, Jasmine, and Belle, I was content to be cast as dog, cat, mouse, or inanimate object. My favorite movies didn’t have princesses. I never loved Barbie dolls or dress up. Instead, I rarely left the house without a Beanie Baby in hand and a Lion King backpack over my shoulder. Nearly every birthday theme in elementary school was the same, and yet I still squealed over the psychedelic frosting patterns of my Scooby Doo cakes.

From the start, I’ve always been intrigued by animals, anthropomorphizing their behaviors and developing a deep empathy for them as a result. With this affection as the groundwork, I first started considering my own choices and their impact on the animal kingdom during a critical time of self-evaluation: college. As a student of history, I was drawn to oral histories and journals, absorbed particularly by the narratives of those on the fringe. Disenfranchisement, protest movements, and deviance were my topics of choice. As my professors revealed stories of systemic inequality, I began to see the interconnectedness of injustices based on race, ability, gender, sexuality, species, and geographic place.

Beginning with a pescatarian diet in undergrad, I picked up books like Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer and cried over films like Bong Joon-ho’s Okja. I wondered at my own moment in time and how I might be remembered by future generations, realizing more and more the magnetic draw of the counter-cultural, revolutionary beliefs from a spectrum of environmental and animal rights activists. Troubled by my complacency, my consumption without questioning, ten years of curiosity and quasi-commitment to animal activism has brought me to pivotal moments of tender clarity: fostering a South Korean kitten with rear leg paralysis, carrying injured wildlife to rehab clinics, struggling through my dedication to veganism, and practicing vulnerability in a classroom of new students every term as I teach about animal rights.

You went to graduate school in South Korea. Did your experience of living in another culture change how you thought about animals?

Yes, absolutely. My focus on animal ethics did grow dramatically during my time in Seoul, but it wasn’t borne out of a uniquely Korean practice or experience. I believe this would have happened anywhere, as long as I allowed myself distance from the comforts and convenience of my hometown in Minnesota. The act of moving to a place far different from mine allowed me to question many aspects of what I deem “normal” or “right.” Living abroad required my attention as well as an openness to confront my assumptions. I began to question why I am excited about certain foods, textiles, smells, and sights, and why other sense experiences cause aversion or discomfort. Where do these preferences originate?

And then, in examining my own cultural lens, I began to question processes. What are the costs of my preferences? How are my patterns of consumption satisfied, and who pays for them?

Seoul was an interesting place to answer these questions. A Midwesterner, I never had to travel far to see dairy farms or hear hunting tales. Years before moving to South Korea, I had already decided I would stop eating meat. I could easily conjure up images of cows grazing beside long stretches of freeways or deer dashing through my family’s backyard. But sushi? I could never give up sushi! Until, that is, I moved to a city nearby the sea, where tanks of octopus, eels, and crabs lined bustling street markets. Here were sentient, intelligent creatures treading water and waiting silently. I was forced to face my own inconsistencies. Why should I spare one animal, but sacrifice another? Why should I care more about a cow than a stingray?

Living in East Asia also added complexity to a passion I saw simply as black or white, right or wrong. I enjoyed long conversations with friends about Eastern and Western cultural perspectives on animals and their use. I was inspired by local, grassroots activists in Seoul, but troubled by the potential of Western activist groups to overtake the already-established movements of a non-Western nation. Life in South Korea helped stoke my passion for animal rights, while also sprinkle some nuance into my spirited convictions. I think the result was a cultivation of grace for any of us trying to do our bests in our contexts.

Tell us about the class you teach. What do you hope students take away from it?

Whatever the topic of the particular section, the purpose of Inquiry Seminar is to fulfill a general education requirement for college writing and speech-making. While half of the class is spent skill-building, the other half is devoted to content in the professor’s area of research. I chose animal ethics out of my own personal studies, but also because I believe it is a great entry-level topic of discussion for first-year students. After all, I think everyone has an opinion on animal ethics, whether they know it or not! We start out our weekly theme with the most obvious way animals are used—the food industry—and branch out each week into lesser known fields and practices. By the end of class, students hopefully have expanded their awareness of the use of animals, noting the unique areas they exist in our everyday lives.

I hope that when my students read articles or hear podcast episodes for this class, they would be both challenged and reassured. I want them to reflect on the permanence of our choices and the sacrifices others make for our daily conveniences, whether those sacrifices come on the part of animals, the environment, or other human beings. However, I also want them to leave the course feeling hopeful. They don’t need to become entirely vegan. They don’t need to ditch their cars and their hobbies. Conscientious in some ways, I still forget my reusable bag at home as I head to the grocery store. I buy vegan shoes made out of single-use plastics. My gut reaction is to swat at an insect rather than stop, consider, evaluate. If we can strive to be environmentally considerate in just a few small and achievable ways, that is a cause for celebration.

What can listeners expect from Seeing Animals? What upcoming interview are you most excited to share with listeners?

Each episode of Seeing Animals highlights a researcher or practitioner in a field related to animal rights or wellbeing, demonstrating the practical application of some themes and ideas in my college course. I am thrilled to have already conducted interviews at animal sanctuaries, a cat cafe, a vegan salon, and in several university institutes. While the mission is to increase awareness of our actions and their consequences on the animal kingdom, this podcast is more than just about seeing animals. We’re seeing their people. It’s an intimate look into the minds and hearts of those who have devoted their lives to the welfare of animals and their environments. Additionally, after each 30- to 40-minute interview, listeners hear the episode send-off delivered from a local vegan or cruelty-free business. This is perhaps the most fun part of producing this podcast, as I can use this little platform to personally thank and support some wonderful restaurants and stores!

I really can’t imagine narrowing down one episode that excites me the most. I mention in the first interview with Jered Camp of Iowa Farm Sanctuary that, yes, this podcast’s purpose is in education. An added benefit? I get to meet my literal heroes! I love that they aren’t politicians, either. They aren’t millionaires. They are average people like any one of us, living out their lives extraordinarily in compassion and resolve. What’s not to love?

For anyone interested in listening, you can also check out our Instagram page (@seeinganimalspod) for a chance to actually see the animals. Every week I will be posting photos of the interviewee’s work and the local shout-out, as well as original episode artwork by Rosie Berglund.

What difference — for better and worse — has Christianity made to animal ethics?

In my 28 years of life, I have never once attended a church service where the pastor mentioned animal ethics. That’s likely easy to believe. What is perhaps harder to stomach is that, in the last several decades of ever-increasing instances of environmental catastrophe, I have never heard a Sunday morning sermon entirely devoted to these crises, not even their impact on human displacement. While I know many Christians and church communities are on the forefront of such issues, I shudder to think of the Church as a whole choosing to be reactive, rather than proactive, to issues of stewarding and protecting nature and all that lives within it.

After all, where is creation’s place in a building constructed to make us consider heaven, not earth? Natural phenomena (and occasionally animals) appear in our songs of worship, the lyrics requesting we praise God for the beauty he made for our enjoyment. First is God, then us, then the rest of creation. This separation—this propping up—of us from the natural world gives permission to use without intention and exploit without question.

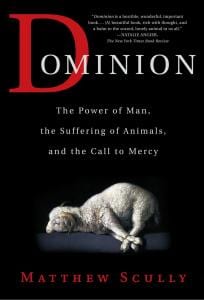

The first person I introduce in my animal ethics course is Matthew Scully, author of the 2003 book Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy. We begin with excerpts from Scully in part because, while he is an animal welfare advocate, he is also uniquely a political conservative, a Christian, and a speechwriter for such leaders as President George W. Bush. His book is named in reference to Genesis 1:24-26. God, having just created Adam and Eve, grants them “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth…” In his analysis of industrial farming in 21st century America, Scully invites us to reflect on the absence of compassion, mercy, and dignity in our exploitation of animals for our gain. Have we lost what God actually desired? Have we misunderstood our place in creation? Should we reimagine “dominion”?

The first person I introduce in my animal ethics course is Matthew Scully, author of the 2003 book Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy. We begin with excerpts from Scully in part because, while he is an animal welfare advocate, he is also uniquely a political conservative, a Christian, and a speechwriter for such leaders as President George W. Bush. His book is named in reference to Genesis 1:24-26. God, having just created Adam and Eve, grants them “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth…” In his analysis of industrial farming in 21st century America, Scully invites us to reflect on the absence of compassion, mercy, and dignity in our exploitation of animals for our gain. Have we lost what God actually desired? Have we misunderstood our place in creation? Should we reimagine “dominion”?

While these points of critique seem grim, I am also hopeful. Story after story in Scripture illustrate radical struggles against societal injustice and dominating power structures, shifting and breaking the boundaries of love of “the other.”

So then, who are our neighbors and who should we love? I believe that, if all the earth holds the splendor and glory of God, then our neighbors are the sentient, living beings in the air, in the ground, in the waters around us, regardless of what function they hold for our personal gain. I am expectant that, as Christians, we will recapture ourselves as a beautiful and integral part of creation, not above or outside of it. That could make all the difference.