Back when work clothes were still necessary for work and academics were doing normal academic things, like attending the lectures of guest speakers and participating in intellectual symposiums, I bought a new skirt–black with embossed blue roses that went beautifully with my strappy blue heels. I wore it for my presentation during a symposium I had organized through the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University. The symposium was Women and the Bible: A Historical Perspective, and it was actually the first time I met my now Anxious Bench co-author Kristin DuMez as I had invited her to speak at one of the sessions.

Back when work clothes were still necessary for work and academics were doing normal academic things, like attending the lectures of guest speakers and participating in intellectual symposiums, I bought a new skirt–black with embossed blue roses that went beautifully with my strappy blue heels. I wore it for my presentation during a symposium I had organized through the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University. The symposium was Women and the Bible: A Historical Perspective, and it was actually the first time I met my now Anxious Bench co-author Kristin DuMez as I had invited her to speak at one of the sessions.

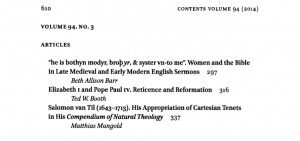

I was younger, thinner, not-yet-tenured, and more idealistic. I had sent the sym posium invitation to several pastors throughout Waco and a few of them, along with some church members, were in attendance. One entire Sunday School class from a local Baptist church even came. My presentation was right after lunch, and it was entitled “Weak and Silent Vessels: The Impact of the English Bible on Women.” My argument was straightforward: English Bible translations affected early modern perceptions of women in the church because they privileged androcentric (male-oriented) language. I have since published some of this research, and more of it is forthcoming in a chapter in my current book project The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth (forthcoming 2021 with Brazos Press).

posium invitation to several pastors throughout Waco and a few of them, along with some church members, were in attendance. One entire Sunday School class from a local Baptist church even came. My presentation was right after lunch, and it was entitled “Weak and Silent Vessels: The Impact of the English Bible on Women.” My argument was straightforward: English Bible translations affected early modern perceptions of women in the church because they privileged androcentric (male-oriented) language. I have since published some of this research, and more of it is forthcoming in a chapter in my current book project The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth (forthcoming 2021 with Brazos Press).

After the lecture, one of the local pastors approached me. He wanted to know why he had never learned any of this. Why wasn’t it included in his seminary textbooks? His comments reminded me of something Catherine Brekus, a path breaking scholar in American Women’s History and professor at Harvard Divinity School, said in Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845. Listen to her words.

“This book is about Harriet Livermore and all of the other female evangelists, both white and black, who tried to forge a tradition of female religious leadership in early America. It is about women’s refusal to heed the words of Paul, ‘Let your women keep silence in the churches,’ despite clerical opposition, public ridicule, and their own fears…Most of all, it is about the importance of remembering a group of forgotten ‘pilgrims’ who force us to question many of our assumptions about the history of women and the history of religion in America.” (p. 4 on the Kindle version)

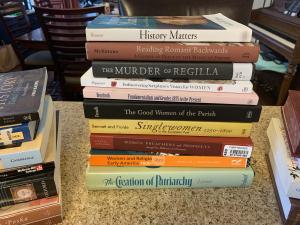

Do you hear what she said? Remembering history, remembering the preaching women in our American historical past forces us to rethink how we understand women. The pastor in my audience that day came with preconceived ideas about women’s roles in the church that were challenged by historical evidence. History matters, as medieval historian Judith Bennett–another pathbreaking scholar–reminds us in the title of her significant work on patriarchy and feminism. History reminds us that Christian women have always fought against patriarchy, and that women can never be written out of leadership as teachers, preachers, evangelists in Christian history.

The problem is that evangelicals simply don’t know this history.

I am taking this problem head on in my book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood, but until then, let me tell you about a few already-published books that would shift the conversation about women’s roles if evangelicals would simply read them. Here are the first three on my list (and more coming in my May and June posts).

-

Margaret Lamberts Bendroth, Fundamentalism and Gender: 1875 to the Present. This short (127 pages of text) and highly-readable history book was published in 1993 by Yale University Press and was written by a Christian woman historian. It is still in print, still affordable, and still relevant. Carefully, thoughtfully she explains how the “hierarchical model of fundamentalist and evangelical family life” was both constructed and reinforced, theologically as well as socially. “Ironically,” Bendroth writes, “though fundamentalists and evangelicals believed they

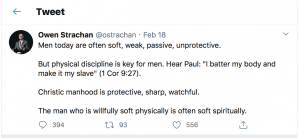

had successfully opposed the modern tide against family dissolution, their solution opened them to significant difficulties. Their model of family life provided women and children little protection from an abusive husband or father, whose domestic power was theoretically unlimited. And it left them entirely unprepared to answer the feminist critique of the nuclear family and the rising aspirations of middle-class women it fostered,” (p. 116). When I first read Bendroth, I felt like a cloud had lifted (seriously). I suddenly understood my evangelical world of small town Texas. I realized that so much I had thought was a part of Christianity was actually constructed very recently by humans (not God). Want to know why Owen Strachan has invented “Christic manhood”?–it starts with the history Bendroth lays out for us. So while we are waiting for Kristin DuMez’s Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (coming out in May), you can get ready for it with Bendroth.

had successfully opposed the modern tide against family dissolution, their solution opened them to significant difficulties. Their model of family life provided women and children little protection from an abusive husband or father, whose domestic power was theoretically unlimited. And it left them entirely unprepared to answer the feminist critique of the nuclear family and the rising aspirations of middle-class women it fostered,” (p. 116). When I first read Bendroth, I felt like a cloud had lifted (seriously). I suddenly understood my evangelical world of small town Texas. I realized that so much I had thought was a part of Christianity was actually constructed very recently by humans (not God). Want to know why Owen Strachan has invented “Christic manhood”?–it starts with the history Bendroth lays out for us. So while we are waiting for Kristin DuMez’s Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (coming out in May), you can get ready for it with Bendroth. -

Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe.

While I suspect many evangelicals have heard of Margaret Bendroth, I suspect most evangelicals have not heard of Merry Wiesner-Hanks (aside from my academic friends and students in women’s history courses). She is one of the foremost scholars on women’s history, gender history, and early modern Europe. I recommend reading almost anything by her. But, I think this text book is a really good place to start. First published by Cambridge University Press in 2008, there are three editions either still in print or available as used copies. The Introduction and first chapter “Ideas and Laws Regarding Women” do a really good job explaining the difference between women’s history and gender history (which I know just from reading Twitter that a lot of evangelicals conflate and confuse) as well as the historical roots for ideas about women’s inferiority and subordination. Wiesner-Hanks will also introduce evangelicals to two ideas we don’t like very much–first, the Reformation era may not have been as glorious as we thought, and second the ideas we equate with Christian womanhood are more global and less Christian than we have been taught. As she writes, “In Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were a time when the domestic nature of women’s acceptable religious activities were reinforced. The proper sphere for the expression of women’s religious ideas was a household, whether the secular household of a Jewish, Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, or Muslim marriage, or the spiritual household of an enclosed Catholic convent” (p. 247 of the third edition). For evangelicals who need a broader and deeper understanding of women’s history, including how Christian history fits into a more global framework–this is where you should start.

-

Katherine L. French and Allyson M. Poska, Women & Gender in the Western Past, Volumes I & II.

This, hands down, is my favorite textbook on women’s history. It is also co-authored by another leading women’s historian, Katherine L. French at the University of Michigan, whose research focuses on women in late medieval and early modern England. Unfortunately this textbook (both volumes) is out of print, but you can still find as very affordable used copies (and maybe we can convince Houghton Mifflin to start printing it again). The textbook walks through the entirety of Western History with women as the primary focus. It provides really great introductions to important historical moments, like the Black Death, the Reformation, the French Revolution, and the great World Wars, and it helps us understand how women have always been a part of these historical moments. The reason I love this text so much is because it shows us something that evangelical women often don’t understand: women have always fought against patriarchy. Discontent isn’t a product of modern feminism, born in the aftermath of WWII. It is a continuous part of history as women have fought throughout history to be able to fulfill their callings as leaders, scholars, scientists, philosophers, business owners, and even preachers. As French and Poska write, “We believe that patriarchy is systemic in Western culture and has been the central force curtailing the movement and rights of women…Gerda Lerner once said, ‘Women’s history is the primary tool for women’s emancipation.’ We hope that this textbook can be one small part of that project,” (p. xiv of Volume II). By showing how integral women have always been throughout history, and by showing how women have always fought against patriarchy, French and Poska more than accomplish their goal.

Happy reading! And stay tuned for more recommendations next time.