Earlier this month, Fr. Lawrence Lucas, author of Black Priest, White Church and a prominent activist priest, passed away. To understand the impact of Fr. Lucas and the significance of the Black Catholic Movement more generally, I interviewed with Dr. Matthew Cressler, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at the College of Charleston and author of Authentically Black and Truly Catholic: The Rise of Black Catholicism in the Great Migration (NYU Press, 2017).

The following highlights of our conversation have been edited for clarity.

On the significance of Fr. Lawrence Lucas

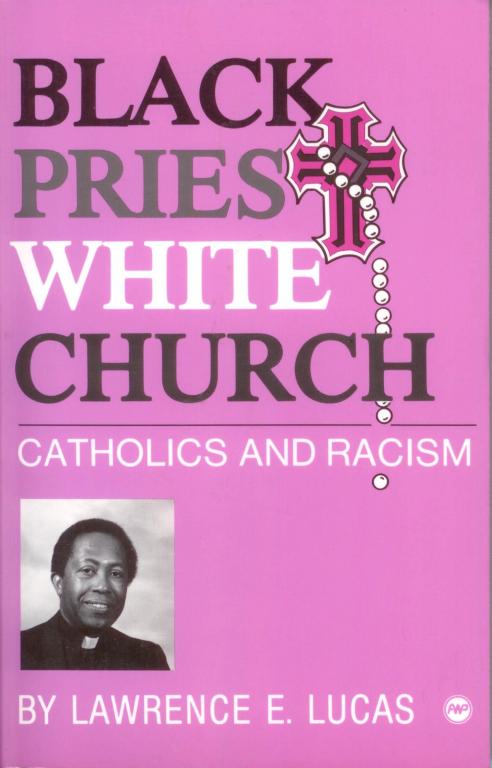

Fr. Lawrence Lucas, who died on April 18, was an activist-priest instrumental in the Black Catholic Movement that transformed the U.S. Catholic church fifty years ago. His memoir-manifesto Black Priest, White Church: Catholics and Racism (1970) perfectly encapsulates the ways Black Power inspired and empowered so many Black Catholics at the time. Lucas is just one among many movement luminaries to pass away in recent years — Sr. Mary Antona Ebo (November 17, 2017), Fr. August Thompson (August 10, 2019), and Fr. George H. Clements (November 25, 2019), to name just a few. Fr. Lucas’ passing hit me quite hard since his book Black Priest, White Church quite literally changed my life. This book served as the spark that ignited the dissertation, which eventually became my book. I was blessed with the opportunity to meet and thank him in person, just a few years ago, at a gathering in Chicago. That book remains one of my top recommendations for anyone interested in learning more about racism in the Catholic Church and what Catholic racial justice could look like.

On the Meaning of “Authentically Black and Truly Catholic”

“Authentically Black and Truly Catholic” is a quote from a pastoral letter that the ten Black bishops of the United States wrote in 1984, and in that statement, they declared that Black Catholics had come of age, as a people, and that they could be both authentically Black and truly Catholic. They were speaking specifically about their worship practices, so that they could incorporate elements of, for lack of a better term, Black Church or Black Afro-Protestant religious practice into Catholic life and be still truly Catholic. In a sense the book offers a kind of twentieth-century history of how we get to that point because the twentieth century sees a tremendous growth in the African-American Catholic population of the United States–in 1940, there are about 300,000 African-American Catholics, and by 1975, there are close to a million, and then by the end of the twentieth century, closer to 3 million. So it’s a period of tremendous growth, but part of what the book argues is that what is means to be both Black and Catholic changes tremendously over that period as well…The book breaks down into two parts, and the first part is about African Americans in the midst of the Great Migrations becoming Catholic, converting to Catholicism in large numbers, and the second half is about the emergence of the embrace of Black Power by certain Black Catholic people, priests, sisters, and the creation of a distinctly Black way of being Catholic as they were understanding it to be. So it’s making interventions into how we understand American religion, how we understand African-American religion, how we understand Catholicism.

On Black Conversion to Catholicism during the Great Migration

What leads to a significant growth is you have African-Americans migrating from the south to urban industrial centers in the North and Midwest and West Coast. Many of those urban industrial centers are majority Catholic, or at least largely Catholic. And African-American migrants are encountering, in the neighborhoods that they are migrating into, Catholic parishes, Catholic institutions, and in some cases, Catholic missionaries, who start to make the decision that in order to preserve Catholicism and Catholic institutions in these transitioning neighborhoods, that they have to fill the emptying pews with African American converts to Catholicism…When [African Americans] come to Chicago, the majority white Catholic response is either to resist their migration to what were perceived as Catholic neighborhoods (by violence or by leaving—white flight to the suburbs) or, in the case of some priests and nuns, to basically shutter Catholic institutions to prevent them from being integrated or desegregated. But there, the story of my book begins by focusing on the exception to the rule, which are white Catholic sisters and priests who dedicate themselves to the conversion of African Americans.

…Conversion tends to happen in and around schools. African American parents quickly identified Catholic schools, Catholic educational institutions, as some of the best opportunities for their children in these neighborhoods to get a good education, and there is a kind of value, as well, to the kind of religious education and discipline that the schools provide. Parents and children aren’t required to convert to Catholicism to enroll. But they are at this time (I’m talking in the 1920s, 30s, 40s, 50s) required to attend Mass, whether or not they are Catholic, and to attend religious instruction, whether or not they are Catholic. Thus, you have Catholic and non-Catholic African Americans alike saying Catholic prayers, engaging in Catholic rituals, being taught that the Catholic church is the one true church, being inculcated in a particular way of being religious, that in some ways, maybe not surprisingly, leads children to go to their parents and say, “Mom, I want to be Catholic,” and in some cases leads to the conversion of entire families.

…So at the height of this Great Migrations-era missionary movement, you would have on Easter Sundays upwards of a hundred to two hundred people being baptized on any given day–mass baptisms where you have a phalanx of priests and servers with water going down the line, baptizing people.

On the significance of centering Black Catholics in American Catholic history

Black Catholics’ embrace of the Black Power movement forces us to see the ways in which the Catholic church has operated often as a white institution…So in 1968, Black Catholic priests and brothers and sisters start caucusing and organizing, kind of inspired by the Black Power movement and galvanized by Martin Luther King’s assassination. And in the midst of that, one of big statements that they make is a declaration that the Catholic church is primarily a white, racist institution that serves and is very much a part of white culture…I think one of the things that you really get when you center Black Catholics is both a kind of theoretical framework for understanding white Catholicism as a racial formation, rather than generically talking about American Catholicism, or immigration Catholicism, or Irish and German and Polish Catholicism. Black Catholics, in their writing, in their activism, in their lives, reveal the kind of whiteness of Catholicism in a particular moment in time. Centering Black Catholics also gives us visions of alternative ways of being Catholic–whether that’s liturgically (the incorporation of Afro-diasporic and Afro-Protestant religious practices into Catholic life) or whether that’s politically (the kind of coalition building and alliances in the Black Power era that leads to Black Catholics and the Black Panther party in Chicago organizing together)…When you center Black Catholics, you both see Black Catholics for who they are, rather than who white Catholics maybe want them to be, and you also see white Catholics for who they are, in the sense of people who have been formed, religiously and racially, in a particular way of being religious.

On the significance of viewing Black religious history through a Catholic (and not Protestant) lens

One of the things that is really interesting about Black Catholic history in the twentieth century is that it simultaneously challenges the notion that there is any one, monolithic thing that we can call the “Black Church,” at the same time that it kind of reinforces the power and the normative notion that Afro-Protestantism holds. Black Catholics are an obvious example, and in the book I compare them explicitly to Muslims and Hebrews and Israelites–all of what Judith Weisenfeld called religio-racial movements. Black Catholics fit, I think, pretty squarely in the first half of the twentieth century into these creative ways that African Americans are fashioning new religious identities for themselves, that extend beyond Afro-Protestantism, beyond what we often call the Black Church. And actually, like those other movements, [Black Catholicism] often is explicitly critiquing that notion of what it means to be Black and religious. So Black Catholics–African Americans who convert to Catholicism in the early twentieth century–are often saying, “Well, I love the quiet dignity of Catholic ritual practice,” by which they are sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly critiquing what they take to be the kind of spontaneity and exuberance and improvisational nature of what they may have experienced in Black Baptist or Black holiness or Pentecostal communities…Centering Catholics really challenges a sense that the Black Church can somehow be used as a synonym for kind of Black religiosity at large.

…Black Catholics in the U.S. didn’t always see themselves as part of the Black Church in the way that it has become much more common now to do so. In fact, what led tens of thousands of African Americans to convert to Catholicism in the early twentieth century was actually, for many of them, an attempt to distinguish themselves from what was increasingly becoming understood as the normative way of being Black and religious.