In October 2017, Vice President Mike Pence gave a sermonic address to the National Space Council. Using language more religious than any other American leader in history had used in a speech about the space program, he said, “As President Trump has said, in his words, ‘It is America’s destiny to be the leader amongst nations on our adventure into the great unknown.’ And today we begin the latest chapter of that adventure. But as we embark, let us have faith. Faith that, as the Old Book teaches us that if we rise to the heavens, He will be there.”

To be sure, the American space program has long been infused with religious discourse and imagery. Buzz Aldrin celebrated communion after Apollo 11 landed on the moon, using bread and a wine chalice provided by his Presbyterian pastor. And this scene stood in stark contrast to Soviet scientists, who made a point of saying that they had never encountered God in space.

Nevertheless, Pence’s declaration has not been true for most American astronauts either. Even born-again Christians who have explored the great unknown typically have not been enchanted by the view. According to Kendrick Oliver’s superb book To Touch the Face of God: The Sacred, the Profane, and the American Space Program, there were several reasons for this.

First, astronauts were scientists and engineers intensely focused on the task at hand. The Gemini 10 astronaut Michael Collins, after working across twenty feet of open space to retrieve materials from an inert Agena rocket, wondered if he might find God outside the spacecraft. “Wrong,” he later recalled. “I didn’t even have time to look for Him.” Indeed, these astronauts were driven, single-minded men who had risen to the very top of their profession. As Oliver puts it, “The space program, for all of the Christians in its midst, for all of its evocations of transcendence, was a product primarily of profane, sometimes prosaic, ambition.”

Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell had a similar experience to that of Collins. As Oliver narrates, “On the moon itself, conscious of public concerns about the expense of the Apollo missions, astronauts raced around seeking to maximize concrete scientific returns, setting up experiments, harvesting innumerable samples of lunar dust, rocks, and soil, the prompting voice of mission control always persistent in their ear.” Collins later explained, “Each minute had to count for something. . . . We kept our wonder in check, or at least under our breath.”

Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell had a similar experience to that of Collins. As Oliver narrates, “On the moon itself, conscious of public concerns about the expense of the Apollo missions, astronauts raced around seeking to maximize concrete scientific returns, setting up experiments, harvesting innumerable samples of lunar dust, rocks, and soil, the prompting voice of mission control always persistent in their ear.” Collins later explained, “Each minute had to count for something. . . . We kept our wonder in check, or at least under our breath.”

This report frustrated journalists, which in turn frustrated Collins, who snarked aloud that the journalists would have preferred a philosopher, a priest, and a poet to three highly trained space specialists.

If astronauts didn’t have time to find transcendence during flight, it was trained out of them before it even began. Christopher Kraft, director of flight operations at the Manned Spacecraft Center, was a faithful Episcopalian, but he noted that his church and the Center existed in two different worlds. He said, “I tried teaching a Bible class, but I lacked the fundamentalist verve and drove people away when I tried too hard to relate the early church to more modern interpretations. It was hard not to be modern when I spent my working days sending man into space.”

In some cases, too much attention to transcendence pushed astronauts out of the space program. Scott Carpenter, writes Oliver, “was judged to have become so distracted by the aesthetic spectacle of space during his flight aboard Aurora 7 that the mission nearly ended in disaster. He never flew again.” For all the theological and cultural investments of American Christians, the space program unrelentingly focused on scientific and secular purposes.

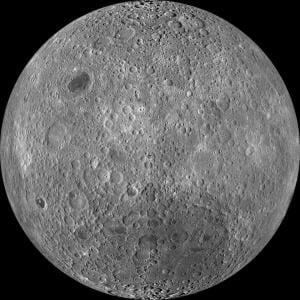

Second, the much-vaunted view was as fascinatingly depressing as it was inspiring. As the Earth shrank in size the further astronauts moved into outer space, the blackness grew all-encompassing, almost annihilating. Collins described it as “a sobering, almost melancholy sight.” The moon was no less unwelcoming. It appeared to be “gray, cratered, and dead, a desolating vision of what could happen to a world.”

Second, the much-vaunted view was as fascinatingly depressing as it was inspiring. As the Earth shrank in size the further astronauts moved into outer space, the blackness grew all-encompassing, almost annihilating. Collins described it as “a sobering, almost melancholy sight.” The moon was no less unwelcoming. It appeared to be “gray, cratered, and dead, a desolating vision of what could happen to a world.”

While John Glenn had perceived the “role of an ordering hand that had set the earth and the planets and stars in their relations to one another,” few others invoked a cosmic divine in similar ways. Jim Lovell of Apollo 8 told a posse of reporters, “I’m kind of curious how all the songwriters can refer to it in such romantic terms.” Buzz Aldrin extracted no profound philosophy, no sublime knowledge, no sense of meaning in the outer reaches. He returned depressed and turned to the comfort of the bottle. As Oliver puts it, “The universe offered no welcome to man, only an education in the negative sublime.”

Indeed, part of the problem may have rested in negative aesthetics that militated against transcendence. The astronauts didn’t have much underwear. There was little personal hygiene. Any food or drink or gas or urine or feces or vomit or moon dust that escaped circulated throughout the cabin for the duration of the trip. According to Oliver, “The odor that accumulated inside Apollo 16 had become so noxious by the time the astronauts splashed down in the sea that the first swimmer to reach their capsule slammed its hatch back in their faces.” Such a disgusting environment surely was not conducive to feeling the presence of God in the depths of the dark.

Perhaps C.S. Lewis was right when he wrote, “If God—such a God as any adult religion believes in—exists, mere movement in space will never bring you any nearer to Him or any farther from Him than you are at this very moment.”