This week a black man was killed by police, just ten miles from where I live in Minnesota.

I want to admit that I have no idea how hard a police officer’s job is. I want to say that we don’t know all the facts of the George Floyd case. I want to say that we should wait for the state (and perhaps federal) investigation to do its work. But however true, I don’t think that’s adequate.

I want to reiterate what I tell my students: that the historian’s task is to be objective, but also to seek empathy — for victims of injustice, but even for those who commit acts of evil. But however true, I don’t believe that’s adequate.

I wanted to spend this week not blogging. I wanted the right to both have a public platform and be silent, knowing that I can’t comment on everything and should probably spend more time listening and less time speaking. But however true, I’m afraid that’s not adequate.

Not that this post is.

But it’s even less adequate than that.

See, I didn’t write those “I want to” paragraphs this morning. I wrote them four years ago, when police shot and killed a black man named Philando Castile, only one mile from where I live in Minnesota — but still a world away from the one I inhabit as a white Minnesotan.

Historians like me spend a lot of time wrestling with American exceptionalism, the idea that this nation stands out from the course of human history as something special. But Minnesotans like me have our own version of that hubris.

Spending ten years away from Minnesota before returning to take my present job only confirmed what I’d been born and raised to believe: that Minnesotans enjoy a uniquely high quality of life, even by American standards. I’ve long believed that we have some of the best health care and education in the country. That we have the best small towns, the most livable big cities, and beautiful parks everywhere hinting at the larger natural beauty just a short drive any direction in the Land of 10,000 Lakes. That we have some of the highest voting and volunteering rates in the country, and that it often pays off in effective, bipartisan government. That even our corporations are model citizens; as long as I’ve been shopping at Target, for example, I knew that it gave 5% of its profits to schools, nonprofits, and other community causes.

We often tell ourselves that we’re a special part of this special nation. And the fact that we don’t say that to anyone else is part of what we think makes us special: in a nation of self-promoters, we Minnesotans are too humble to draw attention to ourselves.

But here we are, at the center of the nation’s attention, and white Minnesotans like me are realizing just how ordinary we are: how typically American we are, and how tragic that is.

For there’s nothing remotely special about living in just another part of a country where racial disparities entrenched over generations leave anger seething just beneath the surface of our self-congratulation.

I remember coming to Virginia from Minnesota in 1993 and telling myself that I’d never seen racism before. Somehow I’d come away from my elite private school education believing that Minnesota was on the right side of all that history.

I knew that Dred Scott’s case for freedom rested in part on his having lived on the free soil of what’s now Minnesota, at the same historic fort that I visited on field trips. I knew that Minnesota raised the first regiment of Union volunteers in the Civil War, and that the First Minnesota had been decimated fighting against slavery on the fields outside Gettysburg.

I didn’t know that two months before that battle, dock workers in St. Paul protested the arrival of a steamboat carrying seventy-five people who had escaped slavery. I didn’t know that they and other freedmen did settle in the state’s capital city, under the leadership of a preacher named Robert Thomas Hickman, who founded Pilgrim Baptist Church. I didn’t know that St. Paul, faced with such diversity, officially segregated its schools in 1865.

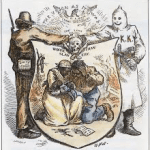

Now, the state legislature banned such discrimination four years later, and in the context of late 19th and early 20th century America, Minnesota’s legislators and judges were relatively progressive in passing and upholding laws guaranteeing equal access. But racial injustice was never too hard to see. Sometimes you didn’t have to work hard at all to notice it, as on June 15, 1920, when thousands of white people broke into a Duluth jail and lynched three black men falsely accused of rape.

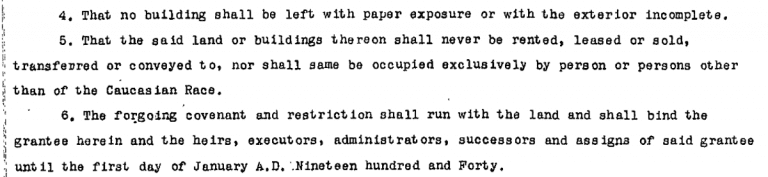

Sometimes the racism was hiding in plain sight, as in the widespread use of racial covenants that kept African Americans and other “objectionable people” from owning property in certain neighborhoods. Just after winning a war against racist tyranny, 60% of Minnesotans responding to a 1946 survey agreed that black people should not be free to live where they chose. (Learn more at the Mapping Prejudice project from the University of Minnesota.) Such devices were banned in the 1950s and 1960s, but to a significant degree they had already succeeded in entrenching segregation in cities like Minneapolis, which had a tiny black community when the first covenants were adopted in 1910 but is now almost 20% African American.

And it’s not just Minneapolis. I was born in St. Paul, in a now-closed hospital that stood less than a mile down University Avenue from the businesses where looting spread yesterday. University makes up the northern border of the Rondo neighborhood, a historic center of the African American community in St. Paul. (The grandfather of the city’s current mayor, Melvin Carter, reflected on growing up in Rondo in this oral history interview.) But Rondo was gutted in the 1950s and 1960s, when planners decided to send the new interstate connecting the Twin Cities (I-94) right through the neighborhood. One in eight black residents of St. Paul lost their home to that project, including a black pastor named George Davis; his grandson, Nathaniel Khaliq, grew up to head the St. Paul chapter of the NAACP.

Despite the efforts of such activists, racial disparities endure in the Twin Cities. A 2018 study found that black households here earn just over 40% of what white households do; the black poverty rate stood then at 32%, and the unemployment rate was three times the white average. And our vaunted schools are home to one of the worst achievement gaps in the nation, with white students twice as likely as their black peers to pass 4th and 8th grade standardized tests and then to be ready for college after 12th grade. (Similar gaps exist for Native American and Hispanic students in Minnesota.)

Then there’s the treatment of Minnesotans of color by our police… You can read a lot more about this history at the state historical society’s MNopedia resource. But the recent past is disturbing enough. According to its own data (reported this week in the New York Times), the Minneapolis Police Department is more likely to pull over, arrest, and use force against the black minority than the white majority, and from 2009 to 2019, that same fifth of the population accounted for three-fifths of the victims of police-involved shootings.

Again, I feel inadequate writing all this. Not just because I’m a historian from Minnesota who barely knows his state’s own history. But because I’m still not sure that learning and writing about it will make any difference.

But it’s the mite I can offer. I remain both hopeful that future historians will explain how a better Minnesota, a better America, came into being and frustrated that such a chapter in our collective story seems so far away. So I’ll end a 2020 post inspired by George Floyd the same way I ended that 2016 post inspired by Philando Castile

I’m a Christian living in America. So I believe that Barack Obama was right that Americans “are strong enough to be self-critical, that each successive generation can look upon our imperfections and decide that it is in our power to remake this nation to more closely align with our highest ideals.” And even if our Union’s political and legal processes prove incapable once again of perfecting itself out of its original sin, I believe that the life, murder, and resurrection of Jesus Christ mean that sin and death do not have the final word in this world, that we can continue to live in the active expectation of hope for a kingdom in which peace, justice, and righteousness truly reign.

But I’m a white Christian living in a part of America that’s ten miles and another world away from where George Floyd was killed. So I’ve got the luxury of believing those things — and then continuing on with my life when they don’t seem to work out as they should.