It’s hard to read the news right now. The ongoing reports from Israel and Gaza are heartbreaking, with civilian deaths, suffering, and tragedy in almost unbearable numbers. Adding another layer to the horror is the rise in hate crimes against Jews, Muslims, and Arabs around the world. In the midst of such suffering, grief, and horrific actions, it feels difficult to know what news coverage to trust, particularly when bias and prejudice is clearly so rampant. How can we navigate remaining informed and advocating for the innocent who are suffering when we are in a media landscape shaped by politics and prejudice?

I’m not sure that I have any clear answers. Some of my co-authors at the Anxious Bench, including Joey Cochran, Jacob Randolph, and Melissa Borja have contributed some helpful perspectives over the past few weeks. From my perspective as a medieval historian, as I’ve reflected on the ongoing news out of Gaza, I think it’s important for us to recognize the long legacy of prejudice and discrimination that most of us have inherited from medieval frameworks of bias against Jews, Muslims, and Arabs. In particular, the medieval framework of religious race, as articulated by Geraldine Heng, feels like it might be helpful for noticing and countering bias and prejudice in current conversations.

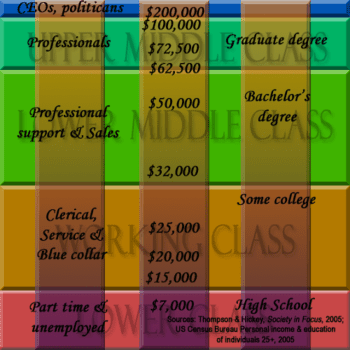

As Geraldine Heng notes in her book The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, the meaning of what constitutes race changes over time, melding with other hierarchical systems like class and gender to form new understandings that draw on older categories and models. And she argues that “the ‘transformational grammar’ of race through time means that the current masks of race are now overwhelmingly cultural . . . our current moment of flexible definitions . . . uncannily renews key medieval instrumentalizations in the ordering of human relations” (Heng p. 20). I’ve discussed Geraldine Heng’s model for understanding medieval race in an earlier post, about medieval topographies. But for understanding what’s going on in today’s news coverage, her model of religious racial othering is particularly important. As Heng explains it, in medieval understandings of race, “religion– the paramount source of authority in the Middle Ages– can function both socioculturally and biopolitically: subjecting peoples of a detested faith, for instance, to a political theology that can biologize, define, and essentialize an entire community as fundamentally and absolutely different in an interknotted cluster of ways” (Heng p. 27).

Both Muslims and Jews were targets for this sort of racial othering during the Middle Ages. The fictions that developed around each group reflect both medieval fears and assumptions, as well as the roots of modern ones. Many of the medieval assumptions about Muslims revolved around stereotypes that they were deceptive and violent. For example, the medieval term “Saracen,” identified by Heng as “the preeminent name by which [Muslims were] known in Latin Europe for centuries,” revolved around an assumption that all Muslims sought to falsely claim to have descended from Sarah, Abraham’s wife, rather than from Hagar, thus trying to steal the birthright of Jews and Christians. (Heng p. 111) Against this backdrop of malicious deception, European Christians imagined Muslims as treacherous figures, seeking to steal what was not theirs at the expense of the church. This vision propelled the Crusades, as well as the development of rhetoric for “holy war” by Bernard of Clairvaux. According to Bernard’s De Laude Novae Militiae, Muslims were malefactors– agents of evil. Thus, Christians could and should kill them without compunction: “If he kills an evildoer, he is not a mankiller, but, if I may so put it, a killer of evil” (Ch. 3). Depicting Muslims as agents of evil, as deceptive and violent, provided justification for unrestrained slaughter.

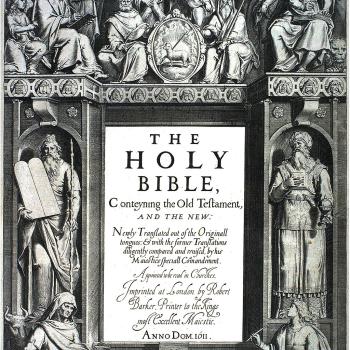

Medieval discrimination against Jews was likewise formed by religious othering, as Jews were portrayed as deceptive and malicious enemies living within European communities, profiting from the suffering of their neighbors. This is clear in one of the most persistent fictions about medieval Jews as child-killers, perpetuated by stories, plays, and images that became known as the blood libel. One example of this blood libel comes from twelfth-century England, from the story that developed around the death of William of Norwich. William’s uncle, a priest, accused the Jews of Norwich of killing the boy as a part of their Passover observations, and the accusations stuck, preserved in texts like The Life and Miracles of St. William of Norwich and echoed in later accounts like those around Hugh of Lincoln. Depicting Jews as child-killers, as those separated from their communities by religion and greed, provided justification for stripping Jews of their property, expelling them from England and other regions, and ultimately executing them.

It’s probably not hard for most of us to recognize loud echoes of the medieval accusations against Muslims and Jews in current media coverage. Many scholars such as Amy S. Kaufman and Paul B. Sturtevant are currently working to understand the medieval past in our present, in order to address modern legacies of medieval and ongoing racial bias, colonialism, and hatred. As we seek to understand our own moment, I think we should all be reading more about the history of the conflicts and of the religious entanglements of bias and politics that are always on display. Most of us might be more familiar with the religious entanglements of modernity– with the connections between dispensationalist understandings of Scripture and Israeli nationalism, for example. But in learning more about the (much) longer history of religious racism, I think we can more clearly recognize it in current media coverage, for without grappling with the subtle (or not-so-subtle) influences of these medieval frameworks, we cannot undo their legacies and the harm they have caused. Perhaps by recognizing medieval legacies in modern conversations, we can at least better navigate the fraught news coverage and discourses around the current tragedies and conflict, becoming better equipped to recognize prejudice and bias in our own responses and the Imago Dei, the image of God, in all.