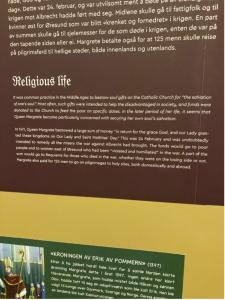

Framed as just another part of the long and interesting reign of Margrete I, the panel pictured below from the Akershus Fortress Museum discusses religion’s role in policy during her later reign, after the dynastic disputes of the late 14th century had been settled and the kingdoms of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden united under a single crown. It was perhaps meant as a throwaway statement during the broader narrative, but the reference to a women’s fund for those ‘violated or debased’ during the wars between Sweden and Denmark from 1388-1389 stood out. What exactly was this? How does it fit with the larger story of Margrete I, a fascinating and underdiscussed figure? And how might Margrete help us think through questions of leadership, policy, and gender today, both within the church and more broadly?

Margrete I: Sovereign Lady and Lord and Guardian of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway

As Vivian Etting argues in her book Queen Margrete I and the Founding of the Nordic Union, Margrete I was one of the most important political figures in Nordic history, something that becomes apparent in even a brief overview of her life. Margrete was born in 1353, the daughter of King Valdemar IV of Denmark; at the age of 6, she was betrothed to Haakon, King of Norway, and moved to the Norwegian court for her education. This took place under the guidance of her tutor Märta Ulfsdotter, a daughter of St. Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373). St. Bridget, well known for her founding of the Bridgettine order, her visions, and her work for religious reform, acted as a model of piety for many medieval figures like Margery Kempe. It seems likely that her emphasis on care for pilgrims, the poor, and the infirm shaped what her daughter taught Margrete, as becomes especially clear when looking at Margrete’s political policies later in life.

At the time of Margrete’s birth and betrothal, the medieval kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden were not yet united, and the power of the Hanseatic League threatened their independence. After her father’s and husband’s deaths in 1375 and 1380, Margrete I was left as regent-ruler of both Denmark and Norway, queen-regent for her young son Olaf. During her time as regent-ruler, Margrete worked to create economic independence for Denmark and Norway, moving them away from the political control of the Hanseatic League. Olaf’s death in 1387 left no direct heirs to the thrones and opened up a new stage of conflict in Scandinavia. However, the politically savvy Margrete not only maintained power over Norway and Denmark, with Denmark’s provincial assembly declaring her to be “sovereign lady and lord and guardian of the entire kingdom of Denmark,” a title that conveyed the authority of a male sovereign, a female sovereign, and a gender-neutral guardian upon her. This triple title is incredibly unusual, both in conveying three types of authority upon a single person and in giving a woman a masculine title. As one chronicler states, she was given these titles because of her divinely granted great wisdom, given to her by God to help navigate the challenging times in which the kingdoms found themselves (Grethe Jacobsen, “Less Favored– More Favored,” p. 7). While Margrete’s title was tied to a requirement that she work with the nobility to designate an acceptable heir, she ruled in her own right until her death in 1412, winning a war against the unpopular Swedish king Albrecht of Mecklenburg in 1397 and establishing the Kalmar Union of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for her great-nephew, Erik of Pomerania.

Kvindefred: Peace Towards Women

Margrete’s political success is remarkable in its own right. But how does her life help us think about questions of gender, leadership, policy, and faith?

Some of what we see in Margrete’s life reflects the influence of St. Bridget of Sweden, the mother of Margrete’s childhood tutor. Bridget, like Margrete, married and became a mother before entering into a position of authority. This was not the usual path for medieval women religious, most of whom gained their spiritual authority through chastity rather than motherhood. But this is part of what made Bridget so influential in her late medieval context: she provided a model of motherly holiness that women like Margrete could follow.

We see some of this motherly piety in Margrete’s policy acts as ruler of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. As Grethe Jacobsen notes, “In 1396, the last year she officially was “sovereign lady and lord and guardian” of Denmark and Sweden, [Margrete] issued an ordinance in which she proclaimed that one should to a higher degree than hitherto respect and enforce peace towards church (pax dei), houses, farms, legal assemblies, workers in the fields – and women, expressed in the word ‘kvindefred’.” Reminders of the church’s peace– the Peace of God, meant to protect Christians and encourage warfare within the boundaries set by the church– were not an unusual thing for a ruler to issue. But, as again noted by Jacobsen, “this is the only place that the word, ‘kvindefred’ appears in medieval Danish legislation. Punishment for rape was common in Danish as well as foreign legislation, but not associated with the other forms for upholding peace in the tradition of pax dei.” (Jacobsen “Less Favored– More Favored,” p. 9). A woman who was a wife, a mother, and a ruler instituted the protection of women as part of a wartime political decree, something that was not the norm for medieval monarchs.

Another place that we see Margrete’s faith and actions reflecting her gender is in her charitable donations. These were not small in number– as her biographer Vivian Etting notes, “hardly any Danish regent has granted so many great and precious gifts to the church as Queen Margrete.” (120) Some of her gifts to the church were fairly normal for medieval rulers: gifts to monasteries, payments for masses in honor of the dead, or the donation of material fabric for churches, like relics, liturgical objects, or art. However, in some of Margrete’s largest donations made in 1411, some unusual provisions appear. In a donation to the Bishop of Roskilde and his chapter, Margrete specified that the bishop should distribute 5,000 marks to “poor churches and monasteries and among Our Lord’s people and the homeless who own nothing, and to help poor virgins, women, and men for their losses during the war” against Albrecht of Mecklenburg. An additional 3,000 marks were set apart specifically for “women and unmarried girls, who if asked can assert that they have been violated and degraded during the wars east of Øresund.” (The donations of Queen Margrete from 1411: ‘Tre gavebreve af Dronning Margrethe fra Aaret 1411’, as translated in Etting, p. 125) This pattern– of specifically recognizing unprotected women and of making restitution for abuse– is again an unusual one for her time, one that perhaps reflects a Bridgettine model of maternal piety and reform. In shaping both political and religious policy in 14th century Scandinavia, having a queen mattered.

Policies and Perspectives

Does having a queen, a woman in leadership, still matter for us today? I think it does. In my Women’s History Month post last year, I talked about the importance of looking beyond those in leadership when we think about church history. That’s still vitally important, for we so often overlook the witness and encouragement from so many faithful Christians when we only focus on leaders. But the life of Margrete I shows us that it’s also important to pay attention to representation in leadership. Margrete I was a wife and a mother who had lost loved ones and knew the dangers that women (even the most powerful women) faced in times of war. These aspects of her identity meant that, unlike so many of her male counterparts, she thought about the needs of women specifically.

Having women in leadership roles in our institutions– universities, governments, and churches– matters because leaders tend to set policies that reflect their own experiences and concerns. A good leader considers the experiences and needs of others, yes, but unless we are in constant conversation with people from different perspectives and backgrounds, we are likely not aware of concerns that they have. Making sure we have people from diverse backgrounds at the table when we make decisions better ensures that the vulnerable are protected, that our decisions reflect the full body of Christ rather than just a part of it. Having a diverse group around the table helps us to love our neighbor as ourselves by hearing their concerns and making them our own. If, like Margrete or Bridget, we are trying to bring about reform and holiness in our own churches and circles, we need to be sure we’re deciding policy at a very big table with space for all.