If you’ve been following the news this past week, you’ve likely seen something about the “God Bless the USA Bible”– a $60 KJV Bible with United States government documents interlaced throughout, marketed and sold by Donald Trump in what he described as a way to celebrate Holy Week. The problems with launching a Bible associated with and promoted by a political figure (particularly during Holy Week) are hopefully obvious to us all (Esau McCaulley’s piece in the New York Times articulates them beautifully). While the website for the text claims that funds from the sale of the expensive Bible will not go directly to Trump’s campaign, it does admit that the site uses Trump’s name, likeness, and image “under paid license from CIC Ventures LLC,” a company of which Trump is president, manager, secretary and treasurer- meaning that this does feed Trump’s personal fortunes, at the very least. The problems with weaponizing the Word of God for nationalist ends should be likewise apparent– and the problems are myriad, as historian and author Jemar Tisby shows in two recent pieces about the “God Bless the USA” Bible and the history of its publication.

My immediate reaction to this new edition was horror at what feels like a blatant misuse of the Word of God. As a scholar of medieval and early modern church history, something that later struck me (because I just couldn’t stop thinking about this) was the use of a Bible associated with the name of a king and produced (at least somewhat) for political ends in a modern political context. As Tisby notes, the use of the KJV version is at least partially because it does not require copyright permission in the US. But the use of the King James Version for this project also makes sense– the KJV-only movement has strong ties to far-right groups and fundamentalist movements. But are there any similarities in the production and goals of the KJV and this project? How does the KJV (reused in this project) help us see even more clearly the problems with political bibles?

Politics and the King James Bible

Some information on the history of the King James Bible is helpful here (and for the interested reader, the 400th anniversary of the translation in 2011 led to a number of works on the text, including David L. Jeffrey’s edited collection The King James Bible and the World It Made and Hannibal Hamlin’s and Norman W. Jones’ collection The King James Bible After 400 Years). As S.L. Greenslade’s work shows, the 1611 version of the text was far from the first English Bible translation, but instead one of many versions produced in the 16th and 17th centuries (S.L. Greenslade, “English Versions of the Bible, 1525-1611” in The Cambridge History of the Bible, Vol. 3, pp. 141-174). In the midst of the theological debates of the English Reformations, Bible translations were serious business- and many of the Bibles produced during this period added in commentaries or notes to help readers understand the text. And it’s against these additions that the 1611 Authorized Version (what would become known as the King James Version) was produced. The “Geneva Bible”, written by English Calvinists exiled in Geneva during the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary, was, in 1604, the most popular version of the Bible in circulation in England– and it had a lot of notes about political structures embedded within, with particularly pointed criticism of church structures and the ways in which secular rulers engaged with the church (Alistair McGrath, “The ‘Opening of Windows’: The King James Bible and Late Tudor Translation Theories” in The King James Bible and the World It Made, p. 18)

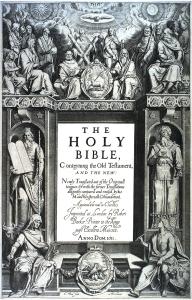

It was these marginal notes that so frustrated King James and pushed him to create a committee for a new Bible translation, one that reflected careful translations of the Greek and Latin, for both accuracy and aesthetic beauty, along with as few additions to the text as possible. David Lyle Jeffrey points out that this was not an insignificant approach: James’ “order that the KJV exclude marginal material other than narrative headings, lexical variants, and identification of New Testament citations of the Old Testament, was to prove of genuine hermeneutical significance,” shaping the understanding of the biblical text through the absence of “historical theological commentary . . . or any sectarian theological opinion” (Jeffrey, “Introduction” to The King James Bible and the World It Made, p. 6). In doing so, as suggested by scholars like Alistair McGrath, it appears that James was attempting to create national unity through a shared scriptural text (McGrath, “The ‘Opening of Windows’: The King James Bible and Late Tudor Translation Theories,” p. 12). With its intentionally minimalistic approach to commentary and marginalia, in the fraught political context of the 17th century, the 1611 translation was undoubtedly a text that reinforced established forms of authority like bishops and kings through some of its translation choices. But it was also a text that made striking efforts to separate itself from explicit political debate. And it’s worth noting that the common name for this translation– the King James Bible– did not come from King James himself. The original frontispiece noted that the text was “newly translated out of the originall tongues, & with the former Translations diligently compared and revised by his Maiesties Speciall Comandment [sic]), but James’ name or image did not appear. Instead, Biblical imagery (not monarchical and not national) formed the decoration for the text.

Authorized Versions, Then and Now

So how do these versions of the Bible from 1611 and 2024 compare? How does this 1611 “Authorized Version,” as it would come to be known, compare to what’s happened this past week? First, we need to note one similarity: whatever else the motivations of the translators involved, the 1611 project did have political ends. James sought to create unity within both church and nation and sought to minimize resistance to his rule. But this, I think, is where the similarities between these two Bibles stop.

First, James (and the translators working under his orders) removed commentary and marginalia alongside the scriptural text, allowing it (whenever possible) to stand on its own. The God Bless the USA Bible instead adds in documents. The translators of the KJV would have rejected this choice, with their understanding that marginalia and framing texts shaped how one read scripture; in this case, adding in US government documents and a nationalist song encourages the reader to view scripture almost solely through an American nationalist view and read nationalist claims into the biblical text. Second, James and his translators actually created a new translation, with the six committees of around fifty translators in total spending seven years working with Greek and Hebrew texts to create an accurate translation. The God Bless the USA Bible represents no new effort at grappling with scriptural texts in their original languages. Finally, James did not create a Bible translation for personal fundraising or gain, but in an attempt to create a better tool for scriptural study (and it’s probably worth noting here that there wasn’t much profit from the 1611 version- in fact, its first printer, Robert Barker, went bankrupt!) (Hamlin and Jones, “Introduction” to The King James Bible After Four Hundred Years, pp. 7-8)

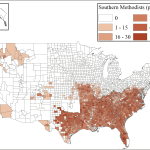

Both the King James Version and the God Bless the USA version might be associated with particular political figures– but that’s where the similarity between the creation of these two editions ends. As chapters from Lamin Sanneh and Philip Jenkins in The King James Bible and the World It Made demonstrate, the 1611 version, with all its archaic language and idiosyncracies, resonates with a global audience, perhaps because of the lack of marginalia that allows the word of God to speak into different nations and cultures– and I don’t think the same can be said of the God Bless the USA version.