At a conference a few weeks ago, in a keynote on medieval cosmologies, the keynote speaker referenced a letter from Bernard of Clairvaux. This letter from the well-known medieval theologian and monk was written to the bishop of a wayward canon, Philip. Philip had been sent by Alexander, Bishop of Lincoln, on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. However, he never made it (to the Jerusalem his bishop sent him to, at least!) Bernard’s letter explained why:

“Your Philip, wishing to go to Jerusalem, has found his journey shortened, and has quickly reached the end that he desired. He has crossed speedily this great and wide sea, and after a prosperous voyage has now reached the desired shore and anchored at length in the harbour of salvation. His feet stand already in the Courts of Jerusalem, and Him whom he had heard of in Ephrata he has found in the broad woods, and willingly worships in the place where his feet have stayed. He has entered into the Holy City . . . He is become, therefore, not a curious spectator only, but a devoted inhabitant and an enrolled citizen of Jerusalem; but not the Jerusalem of this world with which is joined Mount Sinai, in Arabia, which is in bondage with her children, but of her who is above, who is free, and the mother of us all (Gal. iv. 25–26). And this, if you are willing to perceive it, is Clairvaux. This is Jerusalem and is associated by a certain intuition of the spirit, by the entire devotion of the heart, and by conformity of daily life, with her which is in heaven . . .” (Letter 54 in Some Letters of St. Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux)

Yes, you read that right! According to Bernard’s letter, while Philip never reached Jerusalem, he did reach a spiritual Jerusalem: Clairvaux. Philip didn’t forsake his mission, but took up a better mission, albeit not one that aligned with the destination his bishop had in mind.

Maps and Monsters

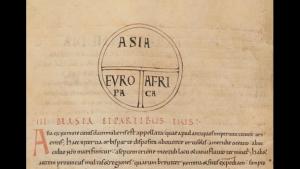

Errant monks always make for an interesting story, but there’s a bit more going on here than that. In the medieval world, geography was more layered than we think of it today. While some maps were certainly developed to help with navigation and travel, other maps, like T-O maps, were meant to help medieval people navigate the allegorical and spiritual meanings of the world. Maps like the Hereford Mappa Mundi, a famous thirteenth-century T-O map, helped medieval people orient themselves in relationship to the story of scripture. T-O maps split the world into thirds, with Asia at the top, above the bar of the T, and Africa and Europe below. In this orientation, sites associated with the biblical narrative and life of Christ were at the center of the map, and thus highlighted as of primary importance both geographically and spiritually. European cities, like Hereford or Clairvaux, were at the geographic and spiritual edges of the medieval understanding of the world. Bernard’s invocation of Clairvaux as a spiritual Jerusalem takes on greater meaning in this medieval context. By placing Clairvaux at the center, Bernard was writing himself into the story of the church, not as someone on the European edges, but as someone in the heart of the gospel narrative: as someone in Jerusalem.

But this layered meaning to geography didn’t end there. As Geraldine Heng explains in her book The Invention of Race in the Middle Ages, medieval European understandings of the world used geographic location and cartography to distinguish themselves from different “races” and marvels in faraway locations. To quote Heng “cartographic and imaginary race issued a grid through which European culture perceived and understood the global races and alien nations of the world,” including those of other religions, particularly Jews and Muslims. (Heng Invention of Race 35). Thus, when we look at the Mappa Mundi, we see monsters and creatures in the margins: Blemmyes, troglodites, cynocephali, and more. And notably, the makers of the Hereford Mappa Mundi and other similar maps correlated distance from the scriptural narrative with physical strangeness and othering. This posed a problem for those living in Hereford and other European Christian communities, on the edges of their physical world yet, by their understanding, part of the story of the church. How did medieval rhetoric address this, keeping to both this cartographic model of race-making and this model of understanding their place in the story of the church?

Bernard of Clairvaux and the European Christians of the Middle Ages lived in a paradox: they were on the edges of the physical world, but at the center of the spiritual one they imagined. By their geographic distance from the centers of the faith, they might have considered themselves aligned with the fantastic creatures and monsters at the other edges of the map. Instead, however, they rewrote the world and story of scripture to put themselves at the center: to make themselves the people aligned with the locations, stories, and significance of the biblical text. In the process of doing so, though, they remade the cultures and peoples of the actual Jerusalem and Middle East into their own image, turning the actual residents of those places into “others” on the edge of the map.

Medieval Mapping and Modern Marginalization

We may not think we kept any of this medieval model of thinking in our modern frameworks for geography– after all, our maps don’t show monsters, and the arrangement of the continents reflects what we can observe from space rather than what we think should be there! But when we think about how we envision the story of the church– and notice how many times we in American culture have assumed that Jesus looks, thinks, and acts just like us– isn’t it clear that we’re doing the same thing? We’re writing ourselves into the center of the biblical text, at the cost of the cultures and peoples that feel far from us, perpetuating systems of racism and exclusion while we do so. Yes, the story of scripture and the Gospel is for all of us, and we can all see parts of our shared humanity, the imago dei, throughout the text. But we need to be sure that we aren’t writing ourselves into the center of a story that ultimately is about Christ bringing us all from the margins to the center. The center of the story isn’t us or our understanding or our culture, it’s the fully divine and fully human incarnate Christ, who lived in a place and time that looks very different from our own. That understanding allows us to step away from this medieval framework that puts monsters on the edges and towards a framework that welcomes all of us, all equally far from the center, into Christ’s kingdom.