This is the first post in a two-part series on the history Southern Baptist perceptions of Palestinians after the creation the state of Israel. The second part will be posted next month.

“Neutrality is not an option.” These words stood out to me as I read the New York Times piece on American evangelicals and support for Israel. The statement came from Jared Wellman, a well-known Southern Baptist pastor in Arlington, Texas, as he tried to give his congregation spiritual guidance on how to think about the latest and bloodiest iteration of the conflict between Hamas and Israel. Wellman’s words were directed most immediately at the status of Hamas fighters—Wellman said Christians shouldn’t view their actions with a false neutrality. But in the broader context of his mid-service talk, Pastor Wellman made it clear that neutrality was not an option in Christian approaches to the land itself. “While Palestinians, when you look at a map, occupy vast portions of the Middle East,” Wellman said, “the Jews have Israel, which is a region roughly the size of the state of New Jersey.” (Here is, I think, a Freudian slip on Wellman’s part. Palestinians don’t occupy vast portions of the Middle East, although people of Arab ethnicity do.) He continued, noting Israel had “generally ceded territories like the West Bank and Gaza to Palestinians…for the purpose of trying to live peacefully with this neighboring community.” Wellman’s sermonette made clear: Christians owed allegiance to Israel.

Four days after the Hamas attacks, the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, the SBC’s policy arm, released an “Evangelical Statement in Support of Israel.” It was quickly signed by an impressive list of Southern Baptist (and some broader evangelical) leaders. The tone of the statement was one of righteous indignation, invoking the “Christian Just War tradition” as a sacred right and exhorting Israel to bear the sword against its foes, even as reports surfaced of the Israeli government cutting off power to hospitals and blocking food and water supplies in what appeared to many as acts of collective punishment against Gazan Palestinians.

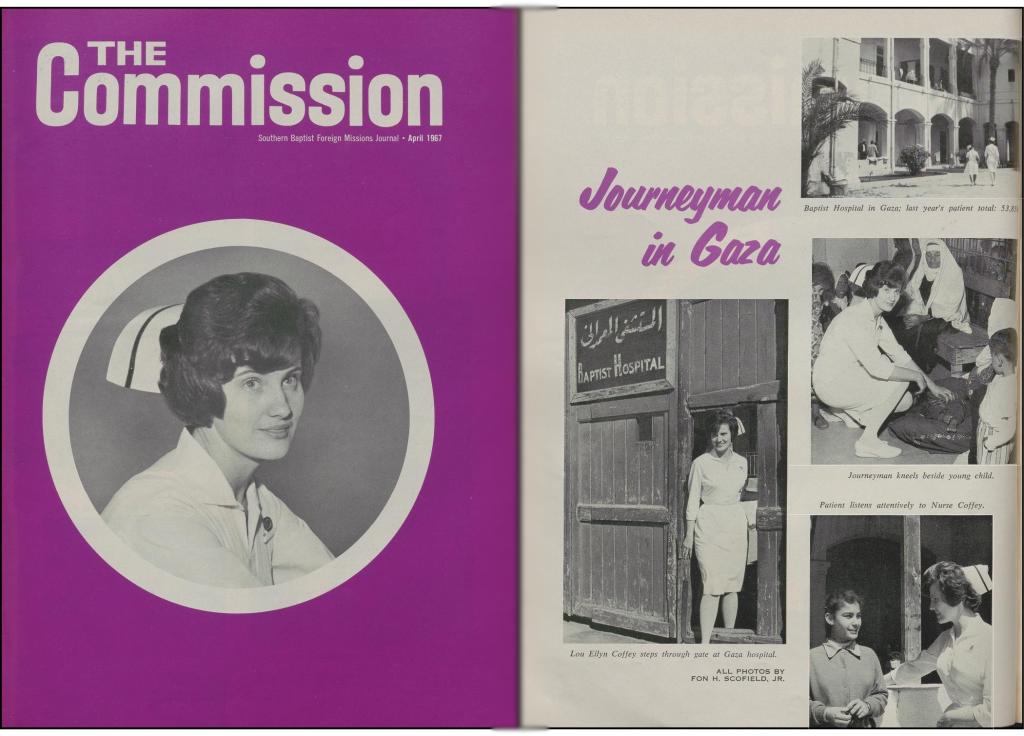

In concert with the ERLC’s statement, the SBC Executive Committee released a brief prayer guide, titled “5 Ways to Pray for Israel.”

The five points included accompanying scripture, clearly pointed at Israel and Jerusalem (which are equivalent in SBC rhetoric despite East Jerusalem belonging to the Palestinian territories) as vehicles for the fulfillment of prophecy. No such prayer guide was released for Gazan Palestinians.

The same week, the International Mission Board of the SBC released their own prayer guide, entitled “Pray for Peace in the Holy Land.” The introduction to the guide reads, “As we watch devastating events taking place in the Holy Land, we are not mere spectators. We don’t just see headlines. We see people. Right now they are injured, frightened, missing. They are lost.” The IMB guide also included scriptures to guide prayer, beginning with Matthew 11:28, “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” The guide asked Southern Baptists to pray for physical needs, lostness, gospel access, and the church in the region. In each instance, the IMB guide focused on shared suffering and spiritual need, avoiding political rhetoric or even specific names (“Israel” does not appear in the guide). “Rockets are launched and the streets are filled with violence,” the guide reads. “Amid this chaos, the lost are living and dying in darkness. While the nations rage, God is still in control and near to all who call out to Him.”

The barrage of responses coming from my Baptist brethren got me wondering about Southern Baptists’ well-documented support of Israel—where were Palestinians in all this? The many resolutions that have come down from Southern Baptist conventions over the years in support of Israeli sovereignty were clear that, while Southern Baptists had a special affinity for the nation of Israel, Palestinians were nevertheless worthy of evangelism and the saving grace of Jesus Christ. But were they, in Southern Baptists’ imaginations, ever worthy of political autonomy or economic opportunity? Did they have a valid claim to the lands of their ancestors? Did all Southern Baptists, like Jared Wellman, merely use Palestinian interchangeably with Middle Eastern Arab—a monolithic people group with no need of country? These were the questions that sent me into the digital archives this week. And what I found challenged my assumptions about the legacy of Southern Baptist attitudes toward the Middle East.

As a preface, the difference in tone and approach between the Executive Committee’s prayer guide and that of the IMB is noteworthy to me. It reflects a longstanding tension within the apparatus of the Southern Baptist Convention—a tension between the focus on evangelistic efforts at home and abroad—the stated goal of the SBC’s existence—and the reality of Southern Baptists as the religious expression of post-Reagan American conservatism. These two poles, missionary political neutrality and Republican political activism, have bounded Southern Baptists’ imaginations on foreign policy matters for nearly the past half century. But Southern Baptists were not always the predictable pro-Israel lobby they have become. And while Southern Baptist silence on Palestinian social and political aspirations has become the status quo, the SBC’s own missionaries have historically sought to temper Zionist zeal with stories of Palestinian suffering and resiliency.

“Are we listening?”

“An immoral miracle”—that’s what SBC Executive Secretary Duke McCall called the creation of national Israel in a November 1950 report published by the Baptist Press. Within a year, McCall would be named the president of Southern Seminary, but in the fall of 1950, he was abroad doing some field survey work for prospective Southern Baptist missions, and he sent back information about the state of relations among the local peoples who inhabited the contested region of what was formerly Palestine. In McCall’s view, national Israel was built in part on the exploitation of Palestinian Arabs who “had inherited [the land] for dozens of generations.” He recalled the scandal of the Deir Yassin massacre, when Jewish militia groups invaded the village of Deir Yassin, sparking fresh animosity between Israelis and Palestinians and a wave of Palestinian flight. By McCall’s reckoning, “the visitor to Palestine is amazed to find whole villages and adjoining orchards abandoned. Homes, shops, goods, everything was left to be appropriated by the new nation.”

McCall’s report attempted to balance the terror of armed conflict and the underhanded actions of the British government with optimism for Israel’s future. “For the people who have built a nation in just two years I have profound admiration,” McCall wrote. “For the future of the nation I have great hope. For the way the nation began there must be some atonement.” He closed his report with a cautious post-script: “The Christian workers in Israel are all pro-Israel. The Christian workers among the Arabs are all pro-Arab. That I advance as proof that there are two sides to the whole matter of Israel-Arab relations.”

Southern Baptist opinions on Palestinians varied widely up through the 1980s. As historian Walker Robins has shown in Between Dixie and Zion, Southern Baptists prior to the formation of modern Israel were all over the map (literally and figuratively) on their approach to Palestine, Jews, and Arabs. Like most Protestants in the early 20th century, Southern Baptists focused on aligning this mysterious land of the East with modern (read: white Protestant) perspectives. Baptists in these years certainly held prejudicial views toward Arabs as backward and uncivilized, the counterpoint to Western modernity. Yet, many early Southern Baptists were concerned more with conversion of the region to evangelical Christianity than with eschatologically motivated political aims. Even after the institution of Israel in 1948, many Southern Baptists seemed little interested in Israel’s end-times role. Missionary and professor, Elmo Scoggin, appealed to Southern Baptists in 1955 to give energy to mission work in Israel, solely because the with creation of an Israeli state, Southern Baptists now had ease of access to thwart Communist aims and proselytize the entire Middle East, especially Muslims.

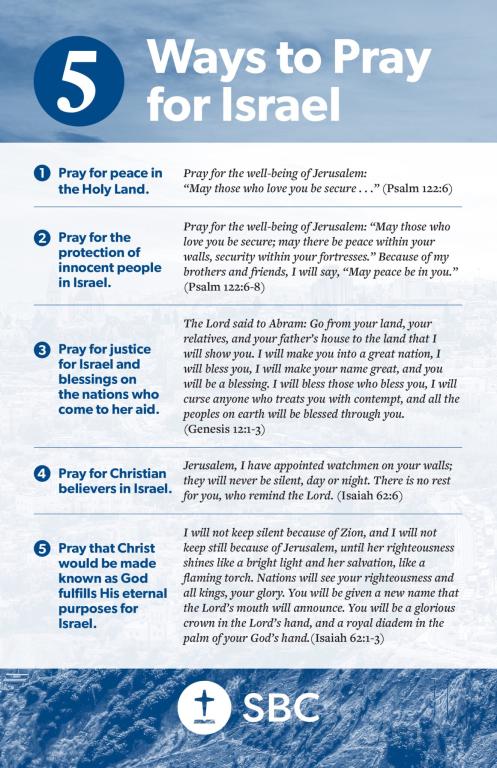

David King, an SBC missionary to Lebanon, was less sanguine than Scoggin about Israel’s formation. Writing the “Arab Viewpoint” in 1967, King argued that the historical suffering of Jews was not reason enough to displace millions of Palestinians. He wrote, “The attitude of Arabs against Israel cannot be understood as anything other than the hatred and anger of a people outraged by a wrong that has caused untold suffering to many of their number for 19 long years.” He claimed that for many, biblicist fervor, not Christian compassion, was behind American Baptist support for Israel. “Christians who, in sentiment or in any other way, have supported the creation of the state of Israel,” King wrote, “cannot escape blame and even guilt for the sufferings of the Arab refugees.” The piece finished with a heartfelt appeal to Southern Baptists to look upon both Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews with sympathy due to their lost spiritual state.

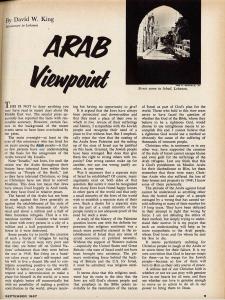

Southern Baptist missionary publications in the late 1960s reveal attempts to empathize with Palestinians’ situation, find common ground between Christianity and Islam, and proclaim Christ as the one who could overcome the religious divides. It was also clear that American missionaries, whose culture promoted religious freedom and religion as a private matter, struggled to understand what seemed like petty skirmishes between Arabs and Jews. It was a time of introspection. After a particularly tense summer in 1967, Martha Lytle wrote about her experience in Commission. She spoke of the personal and corporate pain of war, the cost to Israeli and Palestinian communities beloved by the missionaries, and confessed bewilderment at the resort to violence. She ended her piece with hope that Baptists would be agents for peace: “I am convinced that we who bear the name of Christ can and must join hands over the walls of selfishness, hate, and prejudice—the foundation stones of war. If we do any less, we have failed a world which sorely needs to see in action the love of which we speak. Do we care this much?” Dwight Baker, a seasoned missionary in the region, wrote in 1968 that the new national situation required new ministry strategies—the old tropes of religions locked in cosmic struggle would not work. “If we really love these people,” Baker wrote, “we will be willing to listen to them, to hear all the pain that is in their hearts and in their lives. Then perhaps we can begin to tell them of the joy that is our in the Messiah Jesus, given to us by the Jews and honored by the Muslims. Are we listening?”

“No future in their dreams”

In the era of decolonization, suspicion of missionaries as government agents became a matter of concern for the Foreign Mission Board of the SBC (now the IMB). As the complexity of politics on the global stage became clear, SBC missionaries were instructed to avoid political controversy in their areas of assignment and to cooperate with local authorities wherever possible. In 1974, the Foreign Mission Board adopted a statement of political neutrality, asserting “its concern for persons regardless of their political convictions or involvements, its readiness to work for the spiritual and humanitarian welfare of persons on all sides during times of crisis and war, and its request to missionaries to refrain from actions or statements which might endanger other missionaries or national Christians or jeopardize the witness for Christ in any part of the world.”

Over the course of the 1980s and 90s, it was not uncommon to see reports in the Baptist Press about medical missions in Gaza. Two names appeared in nearly every report: Dona and Dean Fitzgerald. The Fitzgeralds served in Lebanon for eleven years, then served a hospital and nursing school in Gaza from 1978 to 2007 (!). From very early on in their ministry, Dean was circumspect about any grand ambitions for world change in the area. He preferred to think of his family as ordinary Christians, writing in 1976 that he and Dona were “just doing a job that needs doing—like thousands of other Baptists who are at work in the states doing what God has for them to do.” He quipped at the end of his letter, “Not very inspirational, is it?” But Dean and Dona were indeed inspirations to Baptists at home, giving a crucial perspective as to what life on the wrong side of the Gaza-Israeli border was like. In one writeup by FMB correspondent Mike Creswell in November of 1994, Dean told Creswell that he’d become an expert in treating plastic bullet wounds of Gazans who had been shot by Israeli forces. In fact, Dean became so expert in plastic bullet wounds, he wrote an article about the treatment procedure for plastic bullet wounds in children in the medical journal Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics.

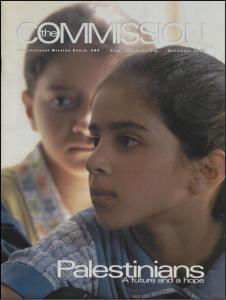

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Southern Baptist missionaries continued to speak up about the plight of Palestinians. Even if their stories were submerged under a wave of premillennialist zeal for Israel, first-hand accounts of the suffering, particularly in Gaza, occasionally broke through. Missionaries were careful to observe the IMB’s policy of political neutrality, but this did not stop them from being honest about the power differential between Israelis and Palestinians, nor about the humanitarian crisis Gaza perpetually faced. Medical missionaries working with the Fitzgeralds at the Baptist School of Allied Health Sciences were occasionally profiled in the Baptist Press, where stories of poverty, despair, and occupation came to the forefront. Gazan medical missionary Nancie Wingo described her service as working among despairing refugees of an endless war, “people who feel misused and neglected.”

Following the passage of the Oslo Accords in 1993, Dean and Dona Fitzgerald held out hope for a new day for Palestinians in the Gaza strip. Despite continued restrictions, Dona sensed a shift in mood in August of 1996: “I think there’s a good deal more pride in the surroundings now that people feel they have possession of the land more or less.” The optimism was to be short-lived. In 2000, after years of unsuccessful negotiation capped off by the failed Camp David Summit, the Palestinian Al-Asqa Intifada uprisings began. When fighting broke out in October 2000, SBC missionaries continued to press home the human cost in Gaza and the West Bank. Paul Lawrence, a longtime missionary among Palestinian Arabs, began coordinating humanitarian aid coming from Southern Baptists in the states. When interviewed about his 2002 initiative, “Project Future and Hope,” Lawrence was quick to explain why this aid was so vital. He spoke of the impact of chronic trauma on Palestinians, especially children. The instability of war meant that many Palestinians couldn’t work—many for years. “There’s food here,” Lawrence said, “but people can’t afford it.” Erich Bridges profiled Lawrence’s work in the December 2002 issue of The Commission as well. Bridges cautiously sidestepped the political issue, calling the perpetually failed peace talks a “blame game” between Israelis and Palestinians. Yet, Bridges’ reporting brought home the terror that Palestinian families felt: 8-year-old girls with gun barrels in their backs, separated families unable to cross over the Gaza border to each other for years on end, hunger and anger feeding fierce thoughts. In the middle of the Intifada storm, Lawrence made clear that part of his goal in bringing Southern Baptists into Gaza for short-term humanitarian projects was to change perceptions in a context where US evangelicals had been politicized by pro-Israeli policies and anti-Arab prejudices. “We…want to change Palestinians’ attitudes toward evangelical Christians–and American evangelical attitudes toward Palestinians.” Amid the fresh violence of the 21st century, Southern Baptist missionaries urged their Baptist siblings to “avoid taking sides and to pray for all involved in the conflict.” The Baptist Press reported one anonymous missionary’s caution: “We Southern Baptists need to be careful not to make statements that condemn one side or the other. Both sides are at fault.”

The call for neutrality went largely unheeded by Southern Baptists at home. In 2002, pastor Jerry Vines made national headlines when he challenged religious pluralism in the US, singling out Muslims as people who venerate a prophet who was a “demon-possessed pedophile” and worship a god who will “turn you into a terrorist.” At the very same convention, the Southern Baptist Convention messengers adopted a resolution, “On Praying for Peace in the Middle East.” The resolution was framed by Zionist language related to “God’s special purposes and providential care” for Israel, as well as a Jewish connection to the land “rooted in the promises of God Himself.” The 2002 Convention took a decided stand in favor of pro-Zionist policies while decrying acts of terrorism and neglecting to mention anything at all about the historical ties or rights of Palestinians. The language of the 2002 resolution was noteworthy. Clearly framed in the shadow of America’s own experience of 9/11 and the War on Terror, “On Praying for Peace in the Middle East” was the first official statement by the Southern Baptist Convention messengers that weighed into Israeli/Palestinian politics. But it would not be the last.