Our standard impression of the Medieval Christian world is distorted. The conventional picture suggests a rigidly-enforced church orthodoxy, any deviation from which meant torture and death. When heresies arose, we are told, they were ruthlessly suppressed, and any and all non-approved religious writings were torched. As I have suggested recently, such a picture works very poorly for the Byzantine world. In the eighth and ninth centuries, orthodoxy was indeed demanded at least in theory, upon pain of exile or death, but that did not prevent large territories being effectively under the control of heretical movements with roots dating back to the earliest Christian centuries. Meanwhile, a great many heretical books and scriptures – including so-called lost gospels – were widely available. (This is the subject of my 2015 book The Many Faces of Christ).

Here is a case in point. Around the eleventh century, in the Byzantine-ruled Balkans, some Christian school or church had a library. On its shelves stood a dazzling array of authentic ancient texts, mainly Jewish in origin, and some dating back to the time of the Second Temple. All those books were wildly heretical by the standards of pretty much any Christian church of the time, east or west, but also of contemporary Judaism. Had they attracted wider attention, bishops and rabbis would have had to toss a coin to decide who got to light the pyre on which they should be destroyed. Yet somebody in authority preserved those texts, and translated them to ensure their wider distribution. Were it not for those translations, every trace of those works would have been lost, to the point that we would never have suspected that any of them ever existed. This is one of the best examples I know of the overwhelming power of sheer chance in determining which books survived from antiquity.

In the nineteenth century, scholars reading medieval Slavonic texts were startled to find that those arcane works had included or adapted much older and more precious materials. Just to take one example, Russian scholars were researching a medieval judicial codex called the Just Balance (Merilo Pravednoe), which was mainly a collection of historical laws and commentaries. It was not surprising that a legal work compiled in the fourteenth century should include abundant religious and Biblical-sounding material, but much of it sounded bizarre. The manuscript proved to contain an important pseudo-Biblical book, 2 (Slavonic) Enoch, or the Book of the Secrets of Enoch, with its vertiginous accounts of heavenly visions and angelic encounters. Different versions of the work survive in twenty Slavonic manuscripts.

Although its dating is controversial, 2 Enoch was probably written in Greek in the first century AD. It was then translated into other languages, including Coptic, but the vast majority of what we know comes from those Slavonic texts. The book offers a fine illustration of how manuscripts evolve over time. In Slavonic, it survives in both longer and shorter versions, and the longer has clearly been adapted for Christian purposes. The shorter version is much older and closer to the Jewish original, lacking references to a Messiah or the resurrection of the dead. This form may take us back to a work written by an Alexandrian Jew somewhere around the first century AD.

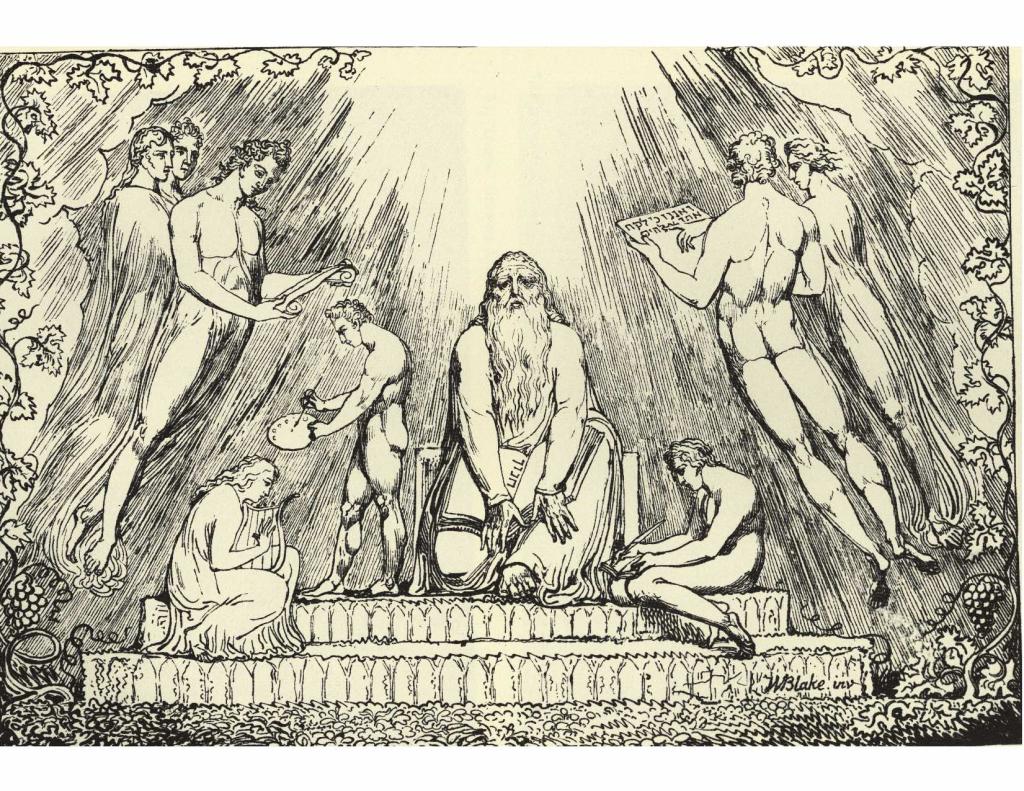

Why this matters so much is that the discovery takes us back to a transformational era in the making of Judaism and early Christianity. From the third century BC, the Jewish world was revolutionized by new ideas of the afterlife, of Heaven and Hell, of mighty angels and demons: Satan and Michael became mighty warriors on either side of the spiritual battle-lines. Some of these works reflect a full cosmic Dualism of the kind we see in the Scrolls from Qumran. These ideas were developed through an outpouring of visionary writings that commonly appeared under the guise of some Biblical author – of Abraham or Enoch or Ezra. As such, they are “false [or falsely attributed] writings,” the pseudepigrapha, and there is a huge scholarly literature on these Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (I write about all this in my 2017 book Crucible of Faith: The Ancient Revolution That Made Our Modern Religious World). The most important part of this literature was attributed to Enoch, and it had an enormous influence on early Christianity. Hence, the discovery of 2 Enoch was momentous. But the Slavonic discoveries went far beyond that one work. Scholars were astonished to discover the wealth and range of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha that existed in the old Slavonic languages. Many of these works, moreover, do not survive in other languages, including in their (usually) Greek originals. Among the works that today exist only or chiefly in Slavonic forms, we find the Apocalypse of Abraham, the Ladder of Jacob, 3 and 4 Baruch, and the Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah. Others bear such suggestive titles as the Testament of Job, Joseph and Aseneth, the Apocryphon of Zorobabel, and the Sea of Tiberias. Some exist in multiple versions, and they have in the process acquired a good deal of extraneous material and folklore. The rediscovery of this “Slavonic Pseudepigrapha” has made huge contributions to the academic study of early Judaism, Christian origins, and the roots of Jewish mysticism.

But the Slavonic discoveries went far beyond that one work. Scholars were astonished to discover the wealth and range of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha that existed in the old Slavonic languages. Many of these works, moreover, do not survive in other languages, including in their (usually) Greek originals. Among the works that today exist only or chiefly in Slavonic forms, we find the Apocalypse of Abraham, the Ladder of Jacob, 3 and 4 Baruch, and the Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah. Others bear such suggestive titles as the Testament of Job, Joseph and Aseneth, the Apocryphon of Zorobabel, and the Sea of Tiberias. Some exist in multiple versions, and they have in the process acquired a good deal of extraneous material and folklore. The rediscovery of this “Slavonic Pseudepigrapha” has made huge contributions to the academic study of early Judaism, Christian origins, and the roots of Jewish mysticism.

But where did this treasure trove come from? The Slavonic lands were converted under the influence of the Byzantine Empire from the ninth century onward, and they followed the Orthodox version of the faith. Remaining in close touch with Constantinople and other great intellectual centers, their churches preserved and translated older Greek texts, including some that had long since vanished from other areas. Even as other churches became nervous about these works, they remained widely available in monasteries and churches spread over Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

We still do not understand the means by which those arcane texts found their way into Slavonic languages. Where might someone have had access to the treasures of Byzantine libraries, but in a Slavonic setting with rich access to Jewish resources and scholarship? We naturally look to the Bulgarian kingdom, which accepted Christianity in the ninth century, and which in 919 became the seat of an autonomous patriarchate. That kingdom had two major cultural and literary centers, namely Ohrid and Preslav, both of which had schools dating from the 880s. Preslav was critical to the development and spread of Cyrillic script, but Ohrid outpaced it in learning and influence. By the turn of the millennium, Ohrid was both the capital of the Bulgarian empire and the seat of the patriarchate. The Byzantines recaptured the city in 1018, reducing the patriarchate to an archbishopric, but Ohrid remained a powerful ecclesiastical seat through the next two centuries. It also stood on the Via Egnatia, the ancient Roman route through the Balkans to the Latin West.

Ohrid was a center for biblical scholarship, both Jewish and Christian. One famous archbishop was Theophylact (1055–1107), who made his church a center of biblical exegesis. After he died in 1107, his successor as archbishop was Leon Mung, a Jewish philosopher who converted to Christianity. In the same era, one of Leon’s old schoolfellows was the city’s senior rabbi, himself a noted biblical scholar. That is not to suggest that either Theophylact or Leon Mung was personally responsible for the process of translating the pseudepigrapha, much of which was already accomplished well before that point. Even so, Ohrid would certainly have provided the right cultural milieu for such an endeavor.

So we have to imagine a library of stellar quality, and we can only speculate what else it might have contained. But we also need to consider the impact that those daring and wildly heterodox writings might have had at the time. In the tenth century, a very influential heretical movement emerged in Bulgaria. These Bogomils taught a strict Dualistic view of the universe, and they in turn influenced the Albigensian movements that were so powerful in Western Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. As scholars explored these ancient Slavonic texts, they were struck by resemblances to the doctrines and imagery of those medieval Bogomils. Some of those Old Testament apocrypha suggested that the material world was created by an inferior God, a Demiurge or Craftsman-Creator.

The Bogomils thus originated and flourished in exactly those regions in which these enticing texts circulated in Slavic languages. Those Dualists had a special taste for several ancient works, including the Apocalypse of Abraham, 2 Enoch, and especially the Vision of Isaiah. These works offered ample materials about angels both good and evil, with a roster of names that would reappear in heretical thought throughout the Middle Ages—Michael and Gabriel in God’s legions; Satanael/Satanail, Sammael, and Azazel in the cause of evil. Readers could easily conclude that one or more of those dark angels was the sovereign of this fallen world.

The similarity between the Pseudepigrapha and much later Dualist ideas could just possibly be a coincidence, but other possibilities suggest themselves. One is that the texts as we have them in their present forms have over time been adapted or edited by writers with a Bogomil axe to grind. In other words, claim some scholars, ancient Jewish texts have been subjected to medieval Dualist editing. That theory has become less fashionable over time, and the alternative is quite evocative. Instead, perhaps the apocrypha themselves helped Eastern European clerics move in Dualist directions during the tenth century. Whether or not those Slavonic texts actually inspired Bogomil dissidence, those scriptures contributed to the movement’s growth and expansion.

That would mean a direct influence from the long-extinct fringes of Second Temple Judaism through the heresies of medieval Europe. Perhaps thirteenth-century Inquisitors were struggling against ideas that originated in Alexandria and Jerusalem at a time when the Second Temple still stood. It’s a remarkable idea.

I have not the slightest idea where those various books had actually been over the course of the first millennium AD, between Palestine and Bulgaria, but I would dearly love to find out. They must have had some exciting travels.

Just a final thought. Take a random year, say 1050 AD. Looking around the whole Byzantine world at that time, how many other libraries might there have been with contents as bizarre and seemingly extensive as what we have seen here? Five? Fifty? How many books did they contain that have since been irrecoverably lost, even to the point of their titles?