“What became of the ten tribes of Israel,” asked former Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow, “when their own country and cities were planted and filled with strangers?” Winslow had a second question: “what family, tribe, kindred, or people was it that first planted, and afterwards filled that vast and long unknown country of America?” As did many Europeans and Americans who came after him, Winslow had one answer to these twin questions. “It is not less probable that these Indians should come from the stock of Abraham,” he wrote, “than any other nation this day known in the world.” Winslow wrote at a time when like-minded puritans anticipated the rapid arrival of the millennium. The king was dead. The bishops were overthrown. Surely Christ’s millennial reign was nigh. Therefore, Winslow expected the imminent conversion of Jews to Christianity. Thus, he urged Protestants in England to support missionary work among the Natives of America as a means to contribute to the fulfillment of ancient prophecy.

“What became of the ten tribes of Israel,” asked former Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow, “when their own country and cities were planted and filled with strangers?” Winslow had a second question: “what family, tribe, kindred, or people was it that first planted, and afterwards filled that vast and long unknown country of America?” As did many Europeans and Americans who came after him, Winslow had one answer to these twin questions. “It is not less probable that these Indians should come from the stock of Abraham,” he wrote, “than any other nation this day known in the world.” Winslow wrote at a time when like-minded puritans anticipated the rapid arrival of the millennium. The king was dead. The bishops were overthrown. Surely Christ’s millennial reign was nigh. Therefore, Winslow expected the imminent conversion of Jews to Christianity. Thus, he urged Protestants in England to support missionary work among the Natives of America as a means to contribute to the fulfillment of ancient prophecy.

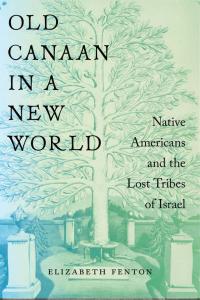

American Indians as Jews? In her wide-ranging Old Canaan in a New World, Elizabeth Fenton traces the rise and fall of this curious but curiously persistent idea through a succession of texts, beginning with the English Presbyterian minister Thomas Thorowgood and ending with the American novelist De Witt Clinton Chipman. With some exceptions, most proponents of the Hebraic Indian theory conceded that they lacked proof but nevertheless found it compelling. They did so, Fenton explains, because “it simultaneously accounted for the presence of American peoples, explained their absence from biblical narratives, and solved a longstanding sacred mystery.” That mystery related to the eighth-century BC conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel. “In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria,” reported Second Kings, “the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria.” Because prophets such as Isaiah and Ezekiel predicted the regathering of the Israelites, many Jews and Christians down through the ages speculated that the descendants of these lost tribes were “somewhere, hidden from view but waiting to reappear.” Perhaps in America.

Any history of the Hebraic Indian theory seems to lead to the Book of Mormon, but Fenton doesn’t rush to get us there. Her analysis of texts by Thorowgood, James Adair, Elias Boudinot, Mordecai Manuel Noah, and William Apess are first rate. Best of all, from my vantage point, is the intellectual and theological scaffolding she erects around these men and their texts. Along the way, readers will encounter probability theory, ethnography, Methodism, and other developments, which help explain why the authors and at least some of their readers embraced the idea that Indians were the descendants of Jews. Fenton’s discussion of Apess – a Pequot and Methodist minister, and one of my favorite figures in the history of American religion – is especially compelling. She suggests that for Apess, the theory was not “a means of inserting himself into the linear timeline of American Christianity” but rather “a site for claiming a past unavailable to white Christians and thereby moving beyond the reach of colonial time.”

The first several chapters of Old Canaan whetted my appetite for Fenton’s engagement with the Book of Mormon and the Latter-day Saints. In many ways, this chapter was worth the wait. Joseph Smith published the Book of Mormon within a culture in which the idea of American Indians as the descendants of Jews had gained wide acceptance. But Smith did more than simply regurgitate old ideas. The new scripture explicitly rejects the notion that the descendants of the ten lost tribes peopled the Americas. Instead, Lehi and his family come from Jerusalem (the southern kingdom of Judah) just prior to its destruction at the hands of the Babylonians. The Book of Mormon notes two other migrations of peoples to the Americas: the Jaredites, who leave at the time of the Tower of Babel; and the Mulekites, another group of Judeans. The Book of Mormon, however, does not ignore the ten allegedly lost tribes. Instead, Jesus in the Americas declares that he will show himself “unto the lost tribes of Israel.” These tribes will have some role to play in sacred history. Earlier in the Book of Mormon, God promises that he will bring about scripture among the “other tribes of the house of Israel” and that “the lost tribes of Israel shall have the words of the Nephites and the Jews.”

Presumably because of these references, Latter-day Saints engaged in sometimes wild speculation about the location of the lost tribes. In 1836, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery reported a vision in which Moses appeared to them and told them that they would help bring about the gathering of Israel, including “the leading of the ten tribes from the Land of the North.” That was hardly the craziest idea. According to some accounts, Smith taught that the tribes had been removed to an extraterrestrial location. Fenton cites a poem of Eliza Snow that advanced this theory: “When the Lord saw fit to hide / The ‘ten lost tribes’ away’; Thou wast divided to provide / The orb on which they stay.” As the decades passed, some Latter-day Saints proposed that the tribes were everywhere from the North Pole to a realm hidden in the center of the earth.

How should one write about a theory that has gained no support from archaeologists, geneticists, and other scientists? At times, Fenton seems to enjoy the absurdity of her material. It can be rather fun to write about a collection of authors who got it all terribly wrong. Thorowgood, for instance, essentially managed to cite his own ideas as evidence for his theory. Fenton does not hesitate to point out his and others’ glaring missteps. “What [James] Adair lacks in knowledge,” she points out, “he makes up for in creativity.” She jokes about the “adorableness” of Adair referring to the segregation of women during menstruation as “lunar retreats.” Fenton also observes that Boudinot’s argumentation “rests on several inaccurate and racist assumptions about American nations, their histories, and their cultures (as well as a paltry understanding of Hebrew).” More fundamentally, she begins by noting that contemporary scholars of the Bible doubt the historicity of the narrative found in I and II Kings, and she is careful to make similar observations about 2 Esdras.

Yet Fenton punts on similar questions surrounding the Book of Mormon. Did Smith use Ethan Smith’s View of the Hebrews as a source or inspiration? Fenton notes scholars on both sides of this question, but she doesn’t offer her own view. It’s been a while since I compared the two texts. I would have enjoyed reading Fenton’s expert opinion. Given her explanation of the Book of Mormon’s original twist on the Hebraic Indian theory, I surmise that she would not bestow much if any credit on Ethan Smith (no relation to the prophet). Fenton simply brackets the more general question of the text’s authenticity as an ancient record, but she treats the Book of Mormon more gently than she does many of the other texts in Old Canaan, perhaps because “the question of legitimacy has proven tyrannical, and unproductive.” Both in this book and elsewhere, Fenton explicates the Book of Mormon within its nineteenth-century American context, so perhaps that is answer enough. Still, what’s the best approach? Should authors offer a straightforward appraisal of the Book of Mormon, or not?

For Fenton, the Hebraic Indian theory is more than a quaint and amusing notion. She contends that it was “a discourse that through several centuries buttressed and contradicted Christian millennialist claims, highlighted and papered over the fractures within American Protestantism, legitimized indigenous and Jewish claims to sovereignty in the Americas, and made space for entirely new religions.” While the previous sentence emphasizes the “malleability” of the theory, Fenton primarily understands the theory as an example of how religious beliefs “abetted the project of settler colonialism and were transformed by it.” Hebraic Indian theory and colonial ideology went hand in hand. “The notion that American settlement marked the fulfillment of a divine order,” she maintains, “justified all manner of colonial horrors.” Yes, the theory might have predicted a glorious future for converted Indians and could be used to criticized white mistreatment of Natives. But at its core, it stripped Native Americans of their own history, eliminated differences among various Native peoples, and supported colonialism if not conquest. It was a tragedy of biblical proportions.