In my book Moral Minority, I tried to show the transnational nature of the evangelical left. The Latin American Theological Fraternity rose to the top in significance. But somewhere behind—and much further to the north—were evangelical radicals associated with the Institute for Christian Studies (ICS), a Reformed think tank and graduate school in midtown Toronto.

The name sounded staid, but the style wasn’t. ICS’s founders, who called themselves Reformationalists, sought to do no less than launch a movement that would reshape North American society and politics through the study of Reformed theology, philosophy, and political theory. ICS adherents castigated what they viewed as the quaint moralisms of their home denomination. The Christian Reformed Church, they felt, was failing to address pressing social issues.

For instance, the denomination’s periodical explained in the mid-1960s that even if John F. Kennedy’s assassination left his agenda incomplete, still Christ could declare, “It is finished.” Hendrik Hart, James Olthuis, Bernard Zylstra, and other young turk Reformationalists at the ICS—typically fiery personalities in their early thirties—denounced such lines as pietistic sophistry. Instead, they envisioned new radical, socially active Reformed communities all over North America.

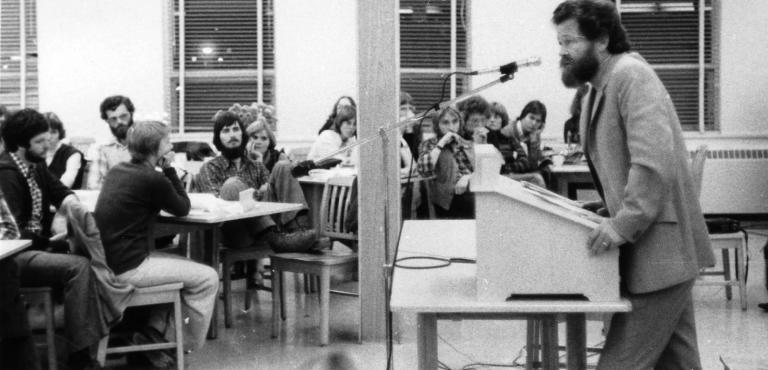

By the early 1970s, the ICS had evolved into an idiosyncratic fusion of Dutch ethnicity and political counterculture. Its constituency came mostly from children of the 185,000 Dutch immigrants who entered Canada between 1947 and 1970 because of a stagnant economy in the Netherlands. Tobacco and marijuana were pervasive at the Toronto school. Baggy jeans and tattered corduroy hung on gaunt frames, and beards proliferated. Communal living in several large houses in Toronto was common. Requiring no assignment deadlines, grades, transcripts, or degrees, ICS nurtured a profoundly anti-establishment ethos that stressed collegiality over hierarchy. Its administrative structure evolved into what faculty member Peter Schouls called “coordinate decentralization,” a system in which employees were accountable to boards and committees, not other individuals. An advertisement for ICS in the early 1970s read, “Are you going to grad school? Try the House of Subversion. … We are subverting the American university structure. We don’t have million dollar buildings. … We aren’t scholarly imperialists. We’ve stopped worshipping the Ph.D. We give guerrilla credentials.”

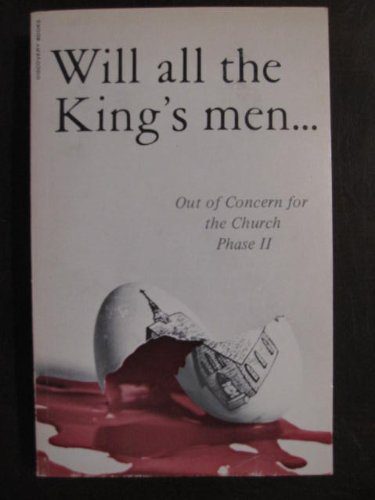

The ICS also released an “explosive little book” called Out of Concern for the Church. One reviewer wrote that “its five essays by as many different Evangelical authors, drag the Evangelical world, kicking and screaming, to the operating room where possibly its life can be saved.” Its authors, with close connections with a renegade Reformed congregation called St. Matthew’s-in-the-Basement, contended that church structures were teetering toward irrelevance. It could only be saved by closing the denomination’s Calvin Theological Seminary, disbanding denominational committees, stripping ministers of their credentials, and letting “ruling elders in the congregations designate as instructors in the Word whosever can bring the Word of Life from the Scriptures.”

Out of Concern for the Church also scorned the American church for complicity in the injustices of American culture. Its authors accused Christians of “awhoring after that great American Bitch, the Democratic Way of Life.” This criticism reflected the ICS’s rigorous critique of mainstream politics, both liberal and conservative. “Our enslavement to technological and economic progress,” wrote Bob Goudzwaard in the movement’s magazine Vanguard, “is leading us down a path to slow death.” Noting the limits of non-renewable energy sources, he argued, “Such consumption cannot go on indefinitely.” Paul Marshall, ICS student and founding member of the Evangelical Committee for Social Action, wrote, “Unrestrained agricorporations, armed with government support and approval, the latest technology, tax breaks, and the ideology of economic progress and efficiency, are killing off the family farms of Canada, creating a massive social upheaval with massive social costs that must be paid by us all.” This hostility toward both conservative and liberal camps reflected ICS’s resonance with New Left critiques of mainstream politics. In 1971 an angry Robert Carvill, the editor of Vanguard, called the United States government “a friend of the anti-Christ” after guards at the Canadian border held up a batch of Vanguard magazines for being “subversive literature.”

Out of Concern for the Church also scorned the American church for complicity in the injustices of American culture. Its authors accused Christians of “awhoring after that great American Bitch, the Democratic Way of Life.” This criticism reflected the ICS’s rigorous critique of mainstream politics, both liberal and conservative. “Our enslavement to technological and economic progress,” wrote Bob Goudzwaard in the movement’s magazine Vanguard, “is leading us down a path to slow death.” Noting the limits of non-renewable energy sources, he argued, “Such consumption cannot go on indefinitely.” Paul Marshall, ICS student and founding member of the Evangelical Committee for Social Action, wrote, “Unrestrained agricorporations, armed with government support and approval, the latest technology, tax breaks, and the ideology of economic progress and efficiency, are killing off the family farms of Canada, creating a massive social upheaval with massive social costs that must be paid by us all.” This hostility toward both conservative and liberal camps reflected ICS’s resonance with New Left critiques of mainstream politics. In 1971 an angry Robert Carvill, the editor of Vanguard, called the United States government “a friend of the anti-Christ” after guards at the Canadian border held up a batch of Vanguard magazines for being “subversive literature.”

ICS’s simultaneous suspicion of mainstream political ideologies and its desire to engage social structures put it in a bind. Students for a Democratic Society—as well as Dutch political philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd and the Dutch Reformed experience in Holland—modeled a way out. Instead of integrating into mainstream culture, ICS confronted the mainstream with separate structures entirely. It promoted separate Christian school systems, the creation of distinctly Christian political parties, and other national institutions. John Olthuis, executive director of ICS, imagined this distinctive vision:

I find myself hurrying along to catch the opening of Parliament in Ottawa. The Christian political party is now the official opposition. … In the Parliamentary galleries I meet the head of the Christian Labor Association of North America, the international association of Christ-believing workers. I leave the gallery and pick up a copy of Voice, the Christian daily newspaper. … I bump into one of the members of the Institute for Christian Curriculum Studies. I mumble my apologies and rush on only to be engulfed by a horde of students buzzing excitedly on their way to the campus of Ottawa’s Christian University. … I take a deep, clean breath. My heart is full of joy, for America is a good place to live, a free place, free for all people to live out of their convictions.

If Toronto’s stark separatism and dismissal of traditional pieties troubled many in Grand Rapids, a common commitment to universal principles of Reformed doctrine and worldly engagement unified them. Both sides agreed, despite their institutional rivalry, that human arrogance could be redeemed only by “the radical message of the gospel.” An intra-Reformed détente was still a decade away, but a commitment to social transformation characterized both camps from the beginning.

Through the 1960s this Reformed vision was beginning to carry over to evangelical circles. To be sure, the Reformationalists were working with a cultural handicap. ICS’s use of marijuana, profanity, tobacco, and idiosyncratic Reformed language alienated mainstream evangelicals. Its countercultural position, though, appealed to evangelical draft-dodgers who welcomed ICS’s hostility toward capitalism, the Vietnam War, and the establishment. And there was a much larger potential constituent base in more moderate sectors of evangelicalism. ICS and Reformed progressives in Grand Rapids thus tacked to the center. They learned to soften their cultural idiosyncrasies and imperial rhetoric.

By the mid-1970s, most of ICS’s new students were non-Dutch, many of them American evangelicals coming from Young Life chapters in Minneapolis and the Coalition for Christian Outreach in western Pennsylvania. Reformed progressives from Grand Rapids also nurtured evangelical ties. Writers in the Reformed Journal (a full half of whose readers in 1973 also subscribed to Christianity Today) and Vanguard learned to invoke Dutch thinkers like Abraham Kuyper sparingly—and when they did, as a way “to start conversations, not to end them.”

Moreover, they went out of their way to publish articles from evangelical sources, especially on issues of social and political concerns. Calvin College and ICS brought in numbers of evangelical guest lecturers, including Samuel Escobar and Rene Padilla of the Latin American Theological Fraternity, Trinity theologian Clark Pinnock, Wheaton philosopher Arthur Holmes, and Post-American Jim Wallis. Some evangelicals—like Mouw, ICS historian Carl McIntire, son of the notorious fundamentalist preacher of the same name; political scientist Paul Henry of Calvin College and son of Carl Henry; and Robert Carvill, a Baptist graduate of the evangelical Gordon College and Trinity College in Deerfield, Ill.—remained in Grand Rapids and Toronto.

They integrated more fully into the Reformed world and interpreted that vision to Billy Graham-style evangelicals. Stopping smoking pot didn’t hurt their cause.