I have been posting on how historians can use American poetry as valuable primary sources, and I have discussed Herman Melville’s Clarel (1876). Another example came rather pressingly to my mind as a result of recent headlines.

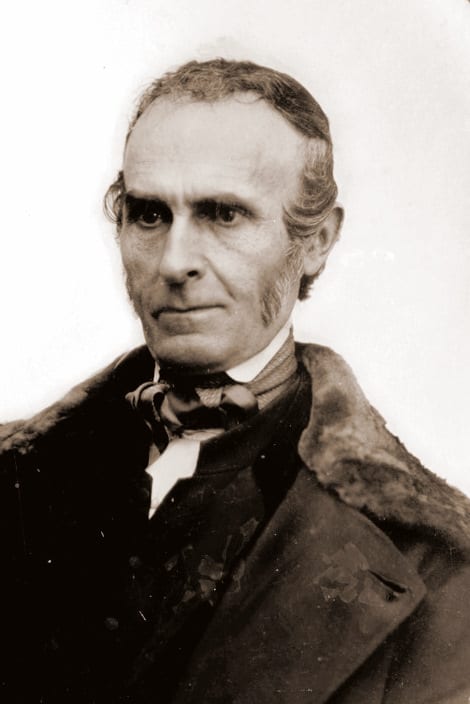

In his day, John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) was an immense public celebrity. He was extraordinarily influential, and was the house bard of the abolitionist movement, especially its religious components. To use an anachronism, the guiding principle of his whole religious creed and political life was that, well, Black lives mattered. Frederick Douglass described him simply as “the slave’s poet, Whittier.” How is that for an endorsement? Whittier was a superbly effective propagandist for abolition, which made him a frequent target of mob violence by pro-slavery groups. All of which makes it depressing to read that some recent protesters would vandalize the statue of him in Whittier, California, on the grounds that he was an **expletive** slave-owner. Whittier? Seriously?

A great many relevant pieces are conveniently collected in Whittier’s Anti-Slavery Poems: Songs of Labor and Reform (1888), and they are a treasure trove for basically the whole period from 1830 onward. In 1832, his original Anti-Slavery Poems were dedicated to William Lloyd Garrison. You can find Whittier poems to illustrate each new crisis and episode in the national debate, into and after the Civil War. The more you read those writings, the better sense you get not just of abolitionism, but of why slavery was so toxic to the whole of American society.

I’ll just cite a couple here. His 1843 poem The Christian Slave was inspired by

a slave auction at New Orleans, at which the auctioneer recommended the woman on the stand as “A GOOD CHRISTIAN! “ It was not uncommon to see advertisements of slaves for sale, in which they were described as pious or as members of the church. In one advertisement a slave was noted as “a Baptist preacher.”

He continues,

A CHRISTIAN! going, gone!

Who bids for God’s own image? for his grace,

Which that poor victim of the market-place

Hath in her suffering won?

The denunciation is all the more fierce when he compares American slaveholders with Islamic Tunis, which had just decided to free its slaves, including Christians. In the meantime,

Oh, from the fields of cane,

From the low rice-swamp, from the trader’s cell;

From the black slave-ship’s foul and loathsome hell,

And coffle’s weary chain;

Hoarse, horrible, and strong,

Rises to Heaven that agonizing cry,

Filling the arches of the hollow sky,

How long, O God, how long?

In 1854, Whittier published The Haschish, a work you can unpack in so many ways. On its surface, it’s a great illustration of Orientalism and stereotypes about the Middle East and the Islamic world, a land of hashish-induced fantasies of dervishes and fanatics, dancing girls and houris, and you probably have a dissertation in that alone. But as a radical abolitionist, Whittier is saying that while the East is driven to bizarre extremes by one lethal drug, namely hashish, the West suffers from its own terrifying hallucinogen, which is Cotton, and the slavery system that goes with it. And what happens to ordinarily sane Christian Americans when they fall under the influence of this dreadful poison?

The preacher eats, and straight appears

His Bible in a new translation;

Its angels negro overseers,

And Heaven itself a snug plantation!

The man of peace, about whose dreams

The sweet millennial angels cluster,

Tastes the mad weed, and plots and schemes,

A raving Cuban filibuster!

The noisiest Democrat, with ease,

It turns to Slavery’s parish beadle;

The shrewdest statesman eats and sees

Due southward point the polar needle.

The Judge partakes, and sits erelong

Upon his bench a railing blackguard;

Decides off-hand that right is wrong,

And reads the Ten Commandments backward.

A filibuster was one of the adventurers who plotted to launch unofficial invasions of Caribbean nations in the hope of grabbing them for the slave South and its plantations – hence the compass needle pointing due south, to find lands to annex. Cuba was an oft-recurring target of these efforts, and it is a minor miracle of US history that Havana never ended up as an American port city, forming a modern-day Caribbean Triangle with Miami and New Orleans.

For the US, slavery was an addictive drug that created hungers that could never be satisfied (yes, I do know that hashish is not actually addictive, but bear with me). One new territorial annexation was too many, and a thousand weren’t enough. Naturally, he thought the incorporation of Texas into the union was a calamity.

Whittier returned to these themes in many writings, especially when denouncing the clergy who served as enablers of the slavery system. See his 1853 poem Official Piety:

Official piety, locking fast the door

Of Hope against three million souls of men,–

Brothers, God’s children, Christ’s redeemed,–and then,

With uprolled eyeballs and on bended knee,

Whining a prayer for help to hide the key!

Today, Whittier might well be worth a couple of brand new statues.