I checked my map to be certain it was the right stop. It was. Caledonian Road station on the  Piccadilly line of the Underground in north London. In 1906, it was brand new. Turn-of-the century glazed tilework spell out “Caledonian Road” on the inner walls while red faience brick frames the large arched windows on the outside. I know now that these distinctive “Edwardian Baroque” architectural features mark the station as one of 40 designed by Leslie Green, Architect to the Underground Electric Railways Co of London between 1903 and 1907. It always seems to me, walking through the tiled corridors of these early tube stations, that the nineteenth-century is not that long ago. I almost expect to see Sherlock Holmes, garbed in Victorian dress and smoking his pipe, waiting on the platform.

Piccadilly line of the Underground in north London. In 1906, it was brand new. Turn-of-the century glazed tilework spell out “Caledonian Road” on the inner walls while red faience brick frames the large arched windows on the outside. I know now that these distinctive “Edwardian Baroque” architectural features mark the station as one of 40 designed by Leslie Green, Architect to the Underground Electric Railways Co of London between 1903 and 1907. It always seems to me, walking through the tiled corridors of these early tube stations, that the nineteenth-century is not that long ago. I almost expect to see Sherlock Holmes, garbed in Victorian dress and smoking his pipe, waiting on the platform.

The gray light of that late summer afternoon still shone brightly, causing me to blink as I emerged from the  dim underground. I walked up the road, turning left on Hillmarton and making my way toward Camden Road. I could see a graffiti-covered church rising over the roof of a nearby gas station, and, as I passed them, I couldn’t help but wonder if the metal arches indicating street numbers were intended to evoke prison vibes. It wasn’t until I saw the Cat and Mouse Library, across the street on Camden Road, that I knew for sure I was in the right place.

dim underground. I walked up the road, turning left on Hillmarton and making my way toward Camden Road. I could see a graffiti-covered church rising over the roof of a nearby gas station, and, as I passed them, I couldn’t help but wonder if the metal arches indicating street numbers were intended to evoke prison vibes. It wasn’t until I saw the Cat and Mouse Library, across the street on Camden Road, that I knew for sure I was in the right place.

I was looking for Holloway Prison. And I had just found it–or at least all that remains of it. The faded brick and concrete walls stood silent, framing an abandoned parking lot. Overgrown vegetation shrouded much of the complex from my eyes, but I could make out bits of barbed wire and tall fences enclosing the grounds. The women’s prison officially closed in 2016 and today the empty buildings still sit, quiet and still.

But, in 1906 when Camden Station first opened, the scene was rather different. Holloway Prison towered as the medieval castle it resembled over the neighborhood, housing as many as 435 mostly working-class female inmates (such as those arrested for prostitution) as well as its most famous residents: suffragettes. Just a year before Camden Station opened, Christabel Pankhurst (the daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the militant branch of the British suffrage movement) and Annie Kenney found themselves serving jail time in Holloway for disrupting a political rally with their suffrage demands. Between 1906 and 1918, Holloway housed hundreds of suffragettes and became the site of one of the darkest moments of women’s fight for the vote–brutal force feedings of suffragettes on hunger strikes and enforcement of the 1913 “Cat and Mouse Act” in which suffragette prisoners in Holloway were released for a short time to regain their strength after hunger strikes, but then immediately rearrested and reincarcerated. The bright purple, green, and white of the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union) suffragette movement still feature in our voting celebrations today, but I am skeptical of how many of my female peers really resonate with the hard and bitter struggle underlying those colors. The right for women to enter a voting booth and have the freedom to make our own political choice has become so ordinary that we sometimes (often?) take it for granted. We can’t remember anything different.

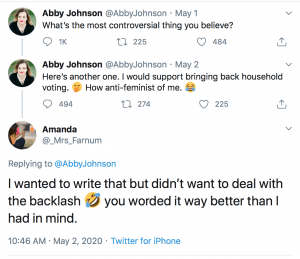

But could we, as women, really ever forget the importance of our right to vote? Abby Johnson’s May 2, 2020 tweet suggests that we could. “I would support bringing back household voting. How anti-feminist of me,” she tweeted with laughing emojis. When I first saw her words, they literally dropped me in my tracks. I just stopped and stared, dumbfounded, after a friend sent me the tweet. What shocked me almost as much as Johnson’s words were the 225 people who liked it, and, while I hope that most of the 274 people who retweeted it did so because of its outrageousness, I suspect some did so because they agreed. Indeed, one woman in direct reply to Johnson, tweeted “I wanted to write that but didn’t want to deal with the backlash you worded it way better than I had in mind.”

For those unaware, Abby Johnson is a controversial but popular pro-life author and speaker. She grew up Southern Baptist (not far from me in Texas, actually), but since has converted to Catholicism. After  debuting her deconversion abortion narrative on Huckabee in 2009, Johnson’s story was featured in the 2019 film Unplanned (which was based on her 2011 book by the same name). She currently has 189,100 twitter followers, and spoke just last week at the Republican National Convention. As The 19th newsroom reported, “On eve of suffrage centennial milestone, RNC to feature speaker supporting policies barring women from voting. Anti-abortion activist Abby Johnson has advocated for a head-of-household voting system that has historically barred women and people of color from casting ballots.”

debuting her deconversion abortion narrative on Huckabee in 2009, Johnson’s story was featured in the 2019 film Unplanned (which was based on her 2011 book by the same name). She currently has 189,100 twitter followers, and spoke just last week at the Republican National Convention. As The 19th newsroom reported, “On eve of suffrage centennial milestone, RNC to feature speaker supporting policies barring women from voting. Anti-abortion activist Abby Johnson has advocated for a head-of-household voting system that has historically barred women and people of color from casting ballots.”

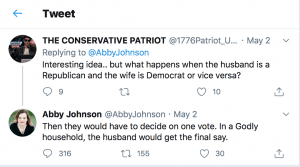

Whoa. Just think about that. “Abby Johnson has advocated for a head-of-household voting system that has historically barred women and people of color from casting ballots.” As disturbing as that is, it is actually her follow-up tweet that worries me the most. When asked how to deal with disagreement, if there was only one household vote, Johnson explained the solution: “Then they would have to decide on one vote. In a Godly household, the husband would get the final say.”

I suspect most folk who saw this tweet simply wrote it off as ridiculous. Like anyone does that.

Except some people do. As sociologist Sally Gallagher describes in Evangelical Identity and Gendered Family Life:

“Hierarchy, Headship, and Having the Final Say. Although a small number of evangelicals reject the notion of husbands’ headship for a model of marriage based on egalitarian partnership, most evangelicals talk about a husband’s responsibility for family leadership as the foundation of evangelical family identity. The cornerstone in that foundation is his responsibility for initiating and moderating family discussions, making final decisions, being primary decision makers, or casting the tie-breaking vote on difficult decisions.”

Evangelical households that adhere to divinely-ordained gender roles often describe the husband’s role with voting language. While this could reflect only his influence in household matters, it does seem to leak out into the political realm. Kristin Kobes DuMez, for example, notes that Paul Coughlin’s No More Christian Nice Guy made a point in 2005 to affirm women’s suffrage. Why did he do this? To push back against the “apparently popular notion ‘within the realm of Christian publishing’ that a man ought to cast the vote for his entire household.”

Indeed, what lays at the heart of Abby Johnson’s tweet is the subject of my forthcoming book–the problem of biblical womanhood. Men lead and women follow, because this (conservative evangelicals believe) is what the Bible teaches.

Yesterday, in my graduate seminar on Women and Religion, we read Phyllis Mack’s insightful article “Religion, Feminism, and the Problem of Agency: Reflections on Eighteenth-Century Quakerism” (Signs 29:1, 2003, 149-177). Mack argues that, for eighteenth-century Quaker women, evangelical Christianity created a “new agency” that was “generated not by the principle of individual free will but by the freedom to do what reason, the Bible, the meeting, and Friends’ own Victorian consciences said was right.” Agency, in other words, can exist for evangelical women without autonomy. As Mack continues, “Since ‘what is right’ was determined by absolute truth or God as well as by individual conscience, agency implied obedience as well as the freedom to make choices and act on them. And since doing what is right inevitably means subduing at least some of one’s own habits, desires, and impulses, agency implied self-negation as well as self-expression.” Women express their freedom to choose by choosing to submit their freedom to God–and, because of their belief in divinely appointed male headship, to submit their freedom also to their husbands.

Johnson’s seemingly old-fashioned statement about the husband’s voting power in the “Godly household” isn’t as out of fashion as we might want to think. The historical foundations for it are still alive and well in 21st century evangelicalism.

Holloway prison is destined to be torn down; the site has been purchased for a significant development project as a residential neighborhood with more than 1000 homes. While good for the Islington area of north London, prote sters have resisted–fearing that if the prison is torn down, it will be forgotten. I don’t worry so much about this. As a historian, I don’t think we will ever forget the suffragettes imprisoned in Holloway–with or without a tangible reminder.

sters have resisted–fearing that if the prison is torn down, it will be forgotten. I don’t worry so much about this. As a historian, I don’t think we will ever forget the suffragettes imprisoned in Holloway–with or without a tangible reminder.

As an evangelical woman, however, I do worry about forgetting. I worry that, because of the emphasis on female submission, evangelicals could be tempted to minimize why the vote matters so much for individual women.

I worry because this is exactly what Abby Johnson has already done.