“Hard-boiled” is the last adjective anyone would use to describe me. I get uncomfortable watching movies with frequent profanities and graphic scenes of sex or violence. So I think my wife has been surprised to see that my COVID quarantine reading tastes have run to detective novels in the mode of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, if not quite James Ellroy.

Now, that larger genre has obvious appeal for a historian. Scholars who patiently sift through the false trails, red herrings, and sheer tedium of archival research in search of clues that unlock mysteries share at least a few vocational traits with detectives. But if I start to imagine myself in that way, I see and hear Sherlock Holmes and Lord Peter Wimsey, not Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe.

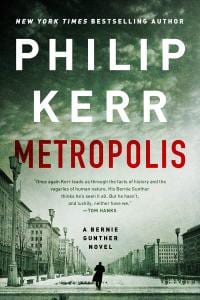

And certainly not Bernie Gunther, the anti-hero of a dozen novels by the Scottish writer Philip Kerr, who died of cancer just before the 2019 publication of Metropolis.

Borrowed from a famous silent film that Philip blogged about earlier this year, that book’s title hints at the setting of the Gunther tales, which bounce around the middle of the 20th century — even reaching (semi-plausibly) to Peronist Argentina and pre-revolutionary Cuba — but always come back to the last years of the Weimar Republic or the first of the Third Reich, when a World War I veteran named Bernhard Gunther becomes a star homicide detective in the Berlin police before being forced into private investigation because of his anti-Nazi politics. (If, like Philip and me, you enjoy Babylon Berlin on Netflix, you’ll feel right at home in the Gunther stories.)

Borrowed from a famous silent film that Philip blogged about earlier this year, that book’s title hints at the setting of the Gunther tales, which bounce around the middle of the 20th century — even reaching (semi-plausibly) to Peronist Argentina and pre-revolutionary Cuba — but always come back to the last years of the Weimar Republic or the first of the Third Reich, when a World War I veteran named Bernhard Gunther becomes a star homicide detective in the Berlin police before being forced into private investigation because of his anti-Nazi politics. (If, like Philip and me, you enjoy Babylon Berlin on Netflix, you’ll feel right at home in the Gunther stories.)

So clearly I’m drawn to Kerr’s tales because I so often teach that period in German history. “The historian will tell you what happened,” E.L. Doctorow once said. “The novelist will tell you what it felt like.” Both fictional and truthful, the Gunther novels help stretch my imagination of what it felt like to live in a war-traumatized society lurching from democratic instability to fascist dictatorship.

I often show my students a scene in the 2005 German movie Sophie Scholl: The Last Days, about the young anti-Nazi activist executed in 1943. As she’s interrogated by a Gestapo officer who literally cannot understand Sophie’s compassion for the lives being snuffed out by the Nazi regime, it becomes clear that we’re watching a horror movie, where lies are truth and crime is justice. That’s how I’ve felt reading stories of a detective who investigates murders in a country ruled by murderers.

Indeed, two leading Nazis — Herrmann Göring and Reinhard Heydrich — become unlikely clients in the Berlin Noir trilogy that introduced Gunther to the reading public in the early Nineties. “The books are morally ambiguous,” admitted Joan Acocella in a Berlin Noir essay in 2016, “and at times the glut of florid nastiness makes them sound worse than ambiguous: frivolous.” Like her, there are times when I want to set Kerr’s books down, or at least skip past the most graphically violent scenes. But in the end, I think Acocella grasps the importance of Kerr’s style:

When I started the Berlin Trilogy, I suspected that Kerr was sometimes waiting to see how much I could take before I’d flee the room…. But eventually I came to feel that the luridness was an act of realism. These sodomies and decapitations: they happened, and not so long ago. Indeed, they are happening now. What do people think is going on in Syria?

Actually, it’s on a pre-war trip to the Middle East that Gunther first meets Adolf Eichmann, who’s as horrifying and insufferable as you’d imagine the Holocaust’s chief bureaucrat to be. But if Eichmann exemplified the “banality of evil” to Hannah Arendt, Acocella concludes that

Kerr’s books are about the banality of goodness. And if it can be highlighted by disgustingness, then bring on the disgustingness. After all, a banal goodness is all we really require. We’re not all Mother Cabrini or even Ralph Nader. What we need is just the ordinary recoil, the ordinary knowledge that at a certain point people can’t go on looking at their fingernails when there are thieves in the store.”

There’s certainly a lesson in there for any teacher or student of this chapter in history. Perhaps I’ll add that to the objectives in my syllabus: “Cultivate an ordinary recoil from disgustingness.”

Not that Gunther sees himself as all that good, banal or otherwise. Offering him a job in If the Dead Rise Not (2009, but the farthest I’ve got so far in the series), an American gangster calls the detective “a man of character.” Bernie scoffs, “I make hard bastards feel good about themselves. They meet me and then go home and read their Bibles and thank God they’re not me.”

Did I mention that our anti-hero is also anti-religious? As a final oddity, I find myself a devout Christian devouring novels about an atheist.

Gunther’s skepticism seems to be the clearest connection between the character and his creator. In promoting a stand-alone novel called Prayer (about a skeptical FBI agent investigating the deaths of atheists), Kerr recalled growing up in a Baptist family in Edinburgh:

…my family was always on first name terms with the Lord Jesus. Sometimes it seemed that his name was forever on our lips. We spoke to him before every meal, when going to bed, and all day it seemed on Sunday… From quite an early age I knew that Jesus and I were not going to get along. Indeed, we stopped being on speaking terms altogether when I was about fourteen and my family came to live in a refreshingly more godless England.

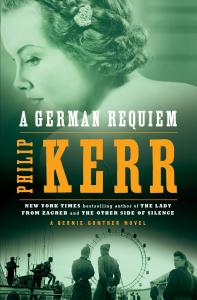

Kerr occasionally draws on his religious upbringing. Bernie Gunther is the kind of atheist who not only quotes chapter and verse of Scripture but likens a woman to Erasmus and himself to Martin Luther — the latter coming within consecutive pages of If the Dead Rise Not, whose title Kerr credits to the 1559 version of the Book of Common Prayer. He not only titled the last book in the original trilogy A German Requiem, but briefly allows Gunther to embrace Christianity. While on a case in postwar Vienna, the detective recalls converting to Catholicism during his stay in a Russian POW camp. “Becoming a Catholic in the full expectation of death only made me more tenacious of life, and after I’d escaped and returned to Berlin I continued to attend mass and to celebrate the faith that had apparently delivered me.” This comes to his mind after a meeting with a shadowy American agent, an otherwise secular Jew who quotes the Tanakh sarcastically but suggests that Gunther’s cooperation could help settle “God’s account” with Germany. (“If only he hadn’t mentioned God,” Bernie grumbles to himself.)

Kerr occasionally draws on his religious upbringing. Bernie Gunther is the kind of atheist who not only quotes chapter and verse of Scripture but likens a woman to Erasmus and himself to Martin Luther — the latter coming within consecutive pages of If the Dead Rise Not, whose title Kerr credits to the 1559 version of the Book of Common Prayer. He not only titled the last book in the original trilogy A German Requiem, but briefly allows Gunther to embrace Christianity. While on a case in postwar Vienna, the detective recalls converting to Catholicism during his stay in a Russian POW camp. “Becoming a Catholic in the full expectation of death only made me more tenacious of life, and after I’d escaped and returned to Berlin I continued to attend mass and to celebrate the faith that had apparently delivered me.” This comes to his mind after a meeting with a shadowy American agent, an otherwise secular Jew who quotes the Tanakh sarcastically but suggests that Gunther’s cooperation could help settle “God’s account” with Germany. (“If only he hadn’t mentioned God,” Bernie grumbles to himself.)

That flirtation with a post-Auschwitz Christianity seems to have been forgotten in the fifteen years it took Kerr to revive his most famous character. In The One from the Other (2006), Bernie enters a Catholic church in Munich and feels his “lip curl with Protestant abhorrence… Not that I ever called myself a Protestant. Not since I learned how to spell Friedrich Nietzsche.” (It doesn’t help that he’s there to meet a sinister Croatian priest who helps Nazi war criminals escape to South America.)

But at least in the three post-trilogy novels I’ve read, it seems like Bernie is also the kind of atheist who finds a godless world anything but refreshing, the kind of skeptic whose chief evidence for disbelief is not philosophical argumentation but his own self-loathing. “It’s easy to stop believing in God when you’ve stopped believing in anything else,” he admits in A Quiet Flame (2008). “When you’ve stopped believing in yourself.”

Here too, he’s describing what it felt for many to live through the disillusioning, embittering events of a genocidal century. But if only by a grace that makes little sense to someone as cynical as Bernie Gunther, here I can recognize that my logic reverses his: in a morally ambiguous world, I can believe in myself, and anything else, because I do believe in God.