Ten days ago Saturday Night Live — of all places — served as the platform for a Christian call to repentance, thanks to the intersection of pandemics past and present.

It started with country singer Morgan Wallen, who was supposed to be SNL’s musical guest on October 10th, only to be disinvited after video surfaced of him partying in a crowded bar without a mask. Because of that COVID-era transgression, singer-songwriter-guitar hero Jack White had to fill in on short notice. His electrifying opening medley featured snippets of his White Stripes track “Ball and Biscuit” and a tune he wrote for Beyoncé, plus these lines from a 1920s blues song inspired by the “Spanish flu”:

The nobles said to the people, “You better close your public schools,

And until death passes ya by, you better close all your churches, too.”

I done told ya, they done told ya, God is comin’ soon.

I done told ya, they done told ya, the Lord is comin’ soon.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhN4M4aS50U

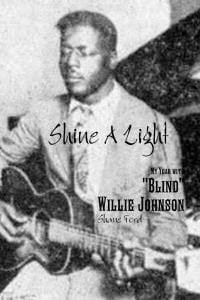

Given that Blind Willie Johnson grew up near Waco, Texas, one of our Baylor contributors should really tell his full story. (Or you can read Michael Hall’s 2010 article in Texas Monthly magazine.) Here’s the thumbnail sketch version:

Having lost his sight in childhood, Johnson made his living as a street musician, pairing his stunning growl of a voice with a distinctive style of slide guitar. Between 1927 and 1930 he recorded thirty songs, sold thousands of records… then virtually disappeared during the Great Depression, dying in Beaumont in 1945.

Johnson’s “violent, tortured and abysmal shouts and groans and his inspired guitar” dazzled one New York critic, who knew little about the Texan, save that he was “apparently a religious fanatic.” Having honed his skills in Baptist and Pentecostal churches, Johnson sang at the crossroads of gospel and the blues. “I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole” was his first single, in January 1928. At the end of that year, Johnson recorded “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning,” “Lord, I Just Can’t Keep from Crying,” and the song that Jack White covered: “Jesus Is Coming Soon.”

Its verses narrate the terrifying days of 1918, when “the doctors they got troubled and they didn’t know what to do.” Why did so many die that even schools and churches had to close? Because:

God sent a mighty disease

It killed many a-thousand, on land and on the seas.

Why would the Almighty kill over 600,000 Americans and perhaps 50 million people around the world?

Well, God is warning the nation, He’s a-warning them every way.

To turn away from evil and seek the Lord and pray.

Astonishingly, the subgenre of Texas-raised, influenza-inspired, apocalyptic blues-gospel doesn’t stop with Blind Willie Johnson. When folklorist John Lomax came to Clemens State Prison Farm in 1939, he met Ace Johnson, an harmonica- and guitar-playing inmate. After Lomax turned on his field recording equipment, this Johnson performed “Influenza,” a song that he had learned from “a holiness boy in Amarillo,” about the outbreak that afflicted Memphis a decade after the more famous flu epidemic. (In fact, the song was first recorded in 1930 by Elder David Curry and his Church of God in Christ congregation.)

“It was God’s almighty hand,” Ace Johnson sang, “he was judging this old land.” Just as “nobles” and people died in 1918, in 1929 God “killed the rich and poor, and he’s going to kill more, / If you don’t turn away from your sins.”

Now, I don’t know that John Lomax, Jack White, or their listeners attached any theological meaning to such words. (White was accepted to seminary earlier in his life, but decided not to become a priest after realizing that “music fulfilled my connection to God in a way that would be unfettered by man’s interpretation and man’s religious ideas.”) After all, Carl Sagan could include Blind Willie Johnson’s voice on the record that accompanied the Voyager One probe into interstellar space, even though he didn’t believe in the Christ whose death inspired Johnson’s most haunting performance.

Now, I don’t know that John Lomax, Jack White, or their listeners attached any theological meaning to such words. (White was accepted to seminary earlier in his life, but decided not to become a priest after realizing that “music fulfilled my connection to God in a way that would be unfettered by man’s interpretation and man’s religious ideas.”) After all, Carl Sagan could include Blind Willie Johnson’s voice on the record that accompanied the Voyager One probe into interstellar space, even though he didn’t believe in the Christ whose death inspired Johnson’s most haunting performance.

But even as a Christian living in the age of COVID, it’s tempting to listen to these songs as cultural artifacts, not theological statements. “I’m more comfortable with natural explanations of such events,” I admitted at my own blog last week. “Attributing inexplicable suffering to ‘God’s just wrath as a punishment to mortals for our wicked deeds’ sits uncomfortably with my belief in a loving, gracious God who sent his Son to save, rather than condemn, a sinful world.”

As a white man with a good job and reliable health insurance, it’s easy to explain a pandemic like COVID in purely epidemiological terms, tinged with perhaps a bit of anger at callous and incompetent political leaders whose failures don’t actually touch me all that deeply.

In this, as many other ways, it’s my privilege to speak of justice without yearning for judgment.

But if I were an incarcerated Black man, I might see God “judging this old land” in a disease that flattens the differences of economic inequality. And if I had spent my life experiencing racial disparities in health care and education, I might see ineffective doctors and shuttered schools differently.

I might even hear today’s versions of such “shout and groans” as the sounds of apocalypse — a “revealing” of truths to which I’d rather turn a blind eye — and an appeal for Jesus to come. Soon.