Last time I posted about the overlap between entertainment, performance, and new religious movements – as I put it, how some entrepreneurial leaders straddle the worlds of the circus tent and the revival tent. Today I will discuss a book that not only explores that idea, but which is in itself a magnificent and woefully under-used resource for American religious history.

Elmer Gantry is a classic American film released in 1960, the title character of which (played magnificently by Burt Lancaster) has become a symbol of religious hypocrisy. The name has entered the language, and really needs little explanation. But here’s the problem. The film was based on a book, a hugely popular 1927 satirical novel by Sinclair Lewis. As with any adaptation, the film simplified and changed the book at many points, and cannot be criticized for that. But the film was so very good, it has totally eclipsed the book. And if you just know the film and not the book, you are missing an immense amount. If you are a historian of American religion, and you don’t know the incredibly rich body of material in this book, you are not taking advantage of a superb set of strictly contemporary observations and commentary about things like – well, for a start, revivalism, mainline churches, Pentecostalism, the New Age, cults, Bible criticism, the prosperity gospel, feminism and faith, and an awful lot of other topics that remain of vital interest today. Also comments on a large number of current and recent religious figures. As you read it, you will be constantly copying out passages and phrases that will supply you with illustrative quotes and epigraphs for the rest of your career.

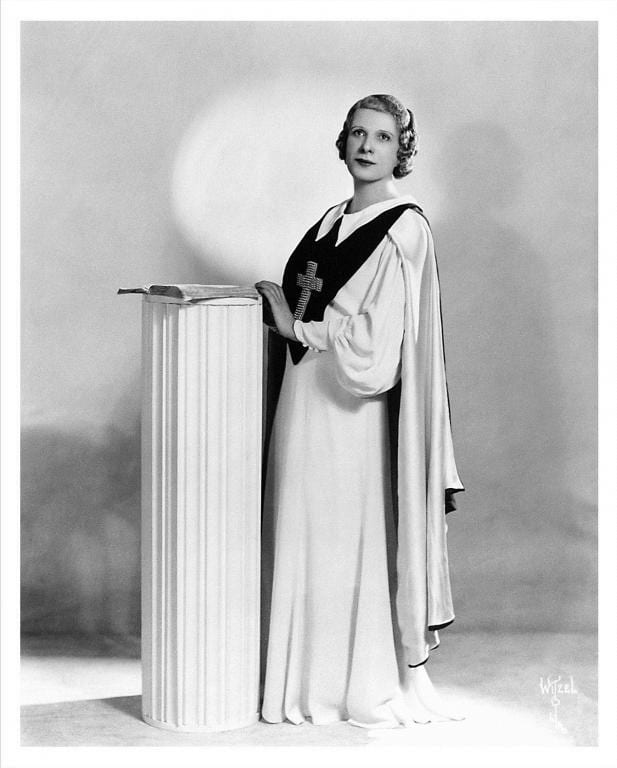

You can find the plot of Elmer Gantry summarized easily. In short, Elmer is a drunken, womanizing, hypocrite who becomes a Baptist minister, a position from which he is soon ejected. He then links up with star revivalist Sharon Falconer, who is heavily based on Aimee Semple McPherson. Through his career, Gantry moves through many settings and scenarios illustrating aspects of the American religion. Returning to my theme of religion as entertainment, as show business, both Elmer and Sharon are consummate performers. They are always on.

As I say, you can find material here for a great many topics. Just as one example of many, do you think that charges of clergy sexual abuse are new in American religious history, a startling discovery of the 1980s? I quote a dialogue among Gantry’s seminary friends near the start of the twentieth century. One character asks, “Why is it that the clergy are so given to sex crimes?” His friends are shocked, but he continues “But if you don’t believe it, Fislinger, look at the statistics of the five thousand odd crimes committed by clergymen–that is those who got caught–since the eighties, and note the percentage of sex offenses–rape, incest, bigamy, enticing young girls–oh, a lovely record!”

As I say, you can find material here for a great many topics. Just as one example of many, do you think that charges of clergy sexual abuse are new in American religious history, a startling discovery of the 1980s? I quote a dialogue among Gantry’s seminary friends near the start of the twentieth century. One character asks, “Why is it that the clergy are so given to sex crimes?” His friends are shocked, but he continues “But if you don’t believe it, Fislinger, look at the statistics of the five thousand odd crimes committed by clergymen–that is those who got caught–since the eighties, and note the percentage of sex offenses–rape, incest, bigamy, enticing young girls–oh, a lovely record!”

This is not just a Lewis hobbyhorse. The dialogue reminds us of the very substantial secularist, anti-clerical, and anti-religious activism of the early twentieth century, which made much of clerical sexual hypocrisy, and which supported a thriving literature with titles like the Crimes of the Clergy. This literature was often ephemeral and is largely forgotten, but it had its impact.

At one point, I was using the book for my work on New Religious Movements, sects and cults. So what do we find? After being discredited as a Baptist preacher around 1910, Elmer gravitates to the emerging New Thought movement, which he frankly terms a racket, with its “pure and uncontaminated bunk.” He attaches himself to

the proprietor of the Victory Thought-Power Headquarters, New York, and not even in Los Angeles was there a more important center of predigested philosophy and pansy-painted ethics … She taught, or farmed out, classes in Concentration, Prosperity, Love, Metaphysics, Oriental Mysticism, and the Fourth Dimension. She instructed Select Circles how to keep one’s husband, how to understand Sanskrit philosophy without understanding either Sanskrit or philosophy, and how to become slim without giving up pastry. She healed all the diseases in the medical dictionary, and some which were not; and in personal consultations, at ten dollars the half hour, she explained to unappetizing elderly ladies how they might rouse passion in a football hero. She had a staff, including a real Hindu swami–anyway, he was a real Hindu–but she was looking for a first assistant.

The “paying customers” were dignified with the title chelas, a Hindu word the proprietor had learned from Kipling’s recent novel, Kim.

Is this a fair or balanced picture of New Thought at the time? Obviously not. But if you want to understand how that was regarded at the time, or the stereotypes that circulated, this is precious.

By the way, Elmer “did very well at Prosperity, except that he couldn’t make a living out of it.”

In later years, he breaks into electronic media:

The Rev. Dr. Gantry was the first clergyman in the state of Winnemac, almost the first in the country, to have his services broadcast by radio. He suggested it himself. At that time, the one broadcasting station in Zenith, that of the Celebes Gum and Chicle Company, presented only jazz orchestras and retired sopranos, to advertise the renowned Jolly Jack Gum. For fifty dollars a week Wellspring Church was able to use the radio Sunday mornings from eleven to twelve-thirty. Thus Elmer increased the number of his hearers from two thousand to ten thousand–and in another pair of years it would be a hundred thousand.

Let’s return to Sharon Falconer, who in the film is a well-intentioned but flawed evangelist, who goes astray sexually. Sexual scandal surrounded the real-life Aimee after her celebrated disappearance in 1926, which was very much in the minds of Lewis’s readers the following year. But in the novel, the fictional Sharon is so much more than a mere hypocrite or power-seeker, and Lewis’s description again illustrates some ideas of the time. Sister Sharon is a covert pagan, who worships Ishtar, Isis, and Astarte in a clandestine chapel dedicated to the Mother Goddess. Sharon “saw herself another Mary Baker Eddy, an Annie Besant, a Katherine Tingley [the Theosophist leader] … she hinted that, who knows, the next Messiah might be a woman, and that woman might now be on earth, just realizing her divinity.”

We might read this as part of the cynical media commentary that Aimee Semple McPherson attracted at the time, but there is more to it. The legendary California commentator Carey McWilliams suggested that Aimee consciously borrowed her distinctive style of presentation from the contemporary New Age and mystical groups that were so prevalent in southern California at this time. Though she had been preaching in the east since 1915, her services became much more ornate following her return to the west in 1918, when she built an influential base in San Diego, and later Los Angeles. She apparently adopted for her own religious movement the “uniforms, pageantry and showmanship” that were associated with Katherine Tingley’s Theosophical settlement at Point Loma, just outside San Diego. Apart from its other functions, that settlement was deeply involved in innovative theatrical productions, which were visually amazing. Do see the many images at this site.

You will recall that the real-life Aimee made daring and dazzling use of theatrical tricks, stunts, and costumes to hold the attention of her congregations. If she drew on Point Loma, her Angelus Temple also looked just down the road to the emerging world of Hollywood. It would be astonishing if Aimee had not also taken inspiration from the dream-like fantasyland of the Panama–California Exposition that was held in San Diego in 1915-17, some remains of which survive today in Balboa Park. I quote Wikipedia on Aimee’s services, and their use of spectacle and performance:

Religious music was played by an orchestra. McPherson also worked on elaborate sacred operas. One production, The Iron Furnace, based on the Exodus story, saw Hollywood actors assist with obtaining costumes. … She became the first woman evangelist to adopt cinematic methods to avoid dreary church services. Serious messages were delivered in a humorous tone. Animals were frequently incorporated,

In the 1930s, the real-life Aimee (if there ever was such a thing) actually went on the vaudeville circuit, where she reputedly had a fling with Milton Berle. You sometimes wonder whether it was Aimee or Sharon who was the fictional character.

Some of Lewis’s observations become downright eerie in light of actual events. In the 1927 novel, Sharon leads a clandestine goddess-worship liturgy in which she persuades Elmer to reads an erotic passage from the Song of Solomon (which as we we are told elsewhere is also his own favorite book). A few years afterwards, Aimee developed her most famous sermon, Attar of Roses, which was based wholly on that same Song of Solomon.

So was Aimee Semple McPherson a closet pagan, or a would-be messiah? I’d be astounded. But if you read Elmer Gantry, you find out what people were saying and thinking of the tine, the kind of ideas that were circulating. If Lewis does not offer an actual biography of Aimee, he had an acute vision of her ideas and vision.

There’s an interesting story of how Sharon Falconer migrated from the novel to the film. In the book, as I say, she is sinister and even megalomaniacal. When the script first circulated in 1958, it would almost certainly fall foul of the Hollywood Code that forbade disrespectful depiction of clergy or religion. Hence, the cinematic Elmer himself loses the ordained status that he originally had in the book, and Sharon becomes a much more nuanced character, with a sincere religious intent. At the film’s climax, she even appears to perform a real miracle, which Lewis would never have countenanced. So the film was released, and triumphed, but at the cost of losing a fascinating character.

If you find a denomination or religious trend in early twentieth century America that the book does not offer cynical or mocking words about, then you have not looked hard enough. But as a historical resource, Elmer Gantry is very valuable indeed. It’s also very funny.

Let me just pre-empt one objection here. I refer throughout to Aimee by her first name. If I was dealing with a male counterpart, would I be so disrespectful and intimate? Would I just use “Billy” when writing of Billy Graham (or Sunday)? Well actually, yes, and I usually do just that.