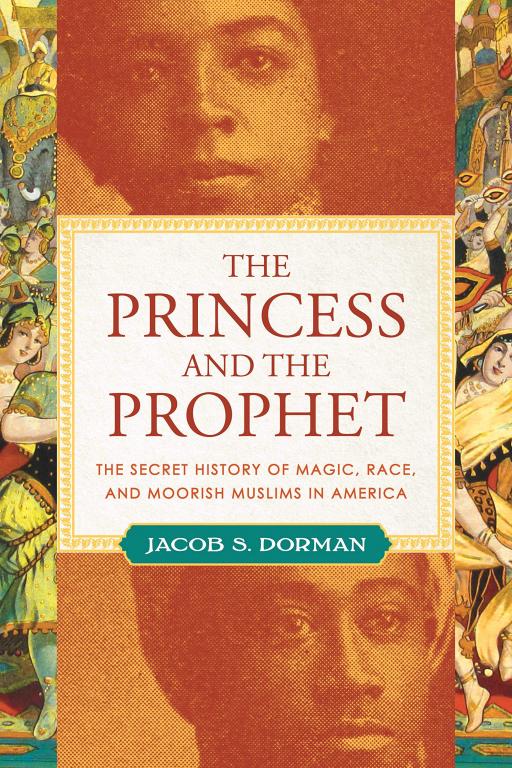

Jacob S. Dorman has a really fine new book out on the historic Black religious sect called the Moorish Science Temple of America, MSTA: the enticing title is The Princess and the Prophet: The Secret History of Magic, Race, and Moorish Muslims in America. That is an important topic in its own right, but it also points to a larger issue in the making of new religions, and one that I don’t think ever gets much coverage, namely the overlap between show business and the making of new and emerging religions. (I stress, this is NOT a review of Dorman’s terrific book).

The Moorish Science Temple emerged in the US in the 1920s, as a pioneering form of (heterodox) Black Islam. It gained a lot of support in urban Black communities, and laid the foundation for the much more successful and better known Nation of Islam. The MSTA was a weird mix of doctrines and influences, with a heavy dose of Black Freemasonry. Its sacred “Koran” borrowed heavily from a channeled New Age pseudo-gospel, Levi H. Dowling’s The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ.

The group’s founder was known as Noble Drew Ali, and Dorman’s great achievement is (at last) to discover his real identity. I quote a recent review by Daniel Pipes:

Mr. Dorman identifies him as John Walter Brister (1879-1929) and devotes much of his book to tracing Brister’s short, eventful life: Born in Carlisle, Ky., he played the cornet in an 1890s vaudeville show, becoming the first-ever black child star on Broadway. He then worked as a “Hindoo” magician, marrying a leading black vaudeville actress of the 1900s, who performed as the “princess” of the title. In the 1910s he became a quack “Egyptian Adept” physician. Finally, he presented himself as a “Moor,” the prophet Noble Drew Ali, and established the MSTA.

The founder died of natural causes. Well, to be more precise, he was heavily involved in faction fights and party politics in Chicago in the late 1920s, and disappeared mysteriously, presumably killed. So in the context, that was quite a natural way to end up.

Dorman’s book is excellent on so many fronts – on African-American history, on new religions, and the urban history of the 1920s, and it is a wonderful read. Here, though, I want to focus on one particular aspect, namely that of the entertainment world, which of its nature depends on play-acting, impersonation, exoticism, dressing up, and spectacle. Several key examples suggest the easy transition from that realm to the world of new or made-up religion.

One now-forgotten name is that of Achmed [sic] Abdullah (1881-1945), who in the 1910s was a famous interpreter of the world of Islam to Americans. Do read this wild and wonderful account of his life and adventures. He was a near contemporary of Noble Drew Ali. According to taste, Abdullah was an Afghan Muslim or else a Russian kinsman of the Tsar. He enjoyed a thriving career as a novelist and screenwriter who trafficked freely in Oriental stereotypes: his film credits included The Thief of Bagdad (1924).

Helping to put the MSTA in context, Hollywood in this era was suffused in the Romantic East. The hottest film was Valentino’s The Sheikh (1921). The coolest place of entertainment was the 1926 Garden of Allah Hotel, named for the enormously popular 1904 novel.

Another example of constant self-reinvention in a Muslim context was Wallace Fard, who around 1930 appropriated some remnants of the MSTA and built them into the embryonic Nation of Islam. Read the Wikipedia entry and just count the countries and backgrounds he is alleged to have come from. What we do know with some confidence is that from 1916 through 1930 or so he was in Los Angeles, the then kingdom of the cults, and of movie fantasies. Fard blamed the creation of the white race on a rogue mad scientist called Yaqub, and that remained NOI teaching, making it yet another of America’s classic science fiction religions. I wonder what films Fard had been watching?

Achmed Abdullah did not found a new religion, but look at his contemporary William Dudley Pelley (1890-1965), about whom I have blogged here previously. Like Abdullah, Pelley was a successful writer and screenwriter very active in Hollywood’s Silent Era. Among his works was the 1922 Lon Chaney film The Light in the Dark, with its mystical Holy Grail theme. From the end of the decade, Pelley claimed that mystical visions had driven him to form a new esoteric mystical order that was also a fascist sect, the Silver Shirts.

The Silver Shirts were explicitly modeled on the German Nazi Party, and Pelley claimed that he was inspired to form his movement on January 30, 1933, the day Hitler became German Chancellor. But Pelley also drew ideas and images from the popular media, as this day marked the first broadcast of the radio western series, The Lone Ranger, with its heroic Rangers and the recurrent silver themes. Pelley’s followers were also Silver Rangers, and that was the title of one of his newspapers.

Although the movement faded during World War II, its influence lasted into the later New Age movement, and was extensively plagiarized by groups like the once extremely popular MIGHTY I AM of Guy and Edna Ballard. Directly or otherwise, Pelley had as lasting an impact on the New Age as on the paramilitary far Right. What he actually believed is up for debate, but perhaps in his mind, the whole thing was one extended film script.

This was all very much part of the Southern California atmosphere during the emergence of Hollywood as a film-making center. In a sense, Hollywood is built on occult foundations. In 1911, Albert P. Warrington founded the Krotona Theosophical settlement here, named for the ancient mystical school of Pythagoras. It offered

the lotus pond and the vegetarian cafeteria. There were several smaller tabernacles as well, a metaphysical library, a Greek theater where The Light of Asia was being played, and numerous dwellings cut into the hillside above and below the winding road … Krotona was one of the most beautiful spots on the planet and a highly magnetized spiritual center as well.

In 1920, Krotona relocated to the Ojai valley, but Hollywood retained its esoteric slant. When magician Aleister Crowley visited Los Angeles in 1918, he was appalled at the clamor he encountered from occult amateurs, the “cinema crowd of cocaine-crazed, sexual lunatics, and the swarming maggots of near-occultists.” [Insert cheap jibe here about some things never changing]

Then you have L. Ron Hubbard, that other prolific writer of fiction and fantasy, who founded his own science fiction religion in the form of Scientology. There is a great account of Hubbard’s surprisingly pivotal role in that science fiction world in Alec Nevala-Lee’s Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

There is plenty of debate about what Anton LaVey was doing before he founded the Church of Satan in 1966, but he claimed a circus background. He certainly had a stage career of sorts as a musician.

There is a nice moment in the 1992 Steve Martin film Leap of Faith, about a successful traveling evangelist, faith-healer, and miracle worker. The film leaves no doubt that he is a cynical fraud, and we glimpse an ad for his earlier secular career as The Great Mentalo, mind-reader extraordinaire. Carny culture has segued directly into the camp meeting, in a way that would have made instant sense to Noble Drew Ali.

Looking at such characters, I think of a song from the musical Sweet Charity, as “Daddy” – Daddy Johann Sebastian Brubeck – evolves from being a beatnik huckster and jazz musician to preach a new gospel of the Rhythm of Life. A Voice instructs him to “spread the picture on a wider screen”:

Daddy, there’s a million pigeons

Ready to be hooked on new religions.

Whatever form they take – stage, screen, or new religion – dreams are dreams, and scripts are scripts. Circus tents can morph into revival tents.

I’ll be returning to questions concerning sects, cults and new religious movements over my next several posts.