Last time I wrote about George Herbert’s poem “The Church Militant” (published posthumously in 1633), with its famous lines about true faith fleeing from Britain to America:

Then shall Religion to America flee:

They have their times of Gospel, ev’n as we.

That seems an appropriate topic during our current commemoration of the Mayflower landing in November 1620. But as I noted, this poem has some oddities, as Herbert was a high Anglican, who at least appeared to be celebrating the distinctively Puritan enterprise to New England. What is going on?

My argument was this. I date the poem to 1629-30, when many Protestants were alarmed about the growth of Catholic influence at court under the French queen Henrietta Maria, and the authoritarian tendencies of Bishop William Laud. This was also the time that the Massachusetts Bay Colony was organizing its settlement. But as I will show, Herbert could be very interested in American matters without favoring Puritanism, or indeed New England. Herbert’s family and friends were deeply and agonizingly involved in American colonization ventures associated with the Virginia Company. The collapse of those enterprises in the mid-1620s left very bad feelings, which are evident in “Church Militant.”

I will also be touching on another very famous topic in Christian history, namely the Anglican community at Little Gidding, which was memorialized by T. S. Eliot, and which is also incomprehensible except for that whole Virginia Company farrago. We can’t understand either George Herbert or Little Gidding without delving into the messy saga of the Virginia Company. We don’t usually tell either of these stories as subsets of business or corporate history, but in fact, we have no option.

As this is quite a complex argument that spills over into a couple of blogs, I have put the whole thing together as a pdf that you can access by going here. It will download as a pdf of the full paper, which also contains quite a substantial bibliography.

Family and Networks

It helps to trace Herbert’s own career around this time. In the mid-1620s he had flirted with a political career and served in parliament, but that idea soon faded. He turned increasingly to religion and in 1629 he decided to seek ordination, which occurred the following year. Also in 1629, he married Jane Danvers, of whom I will have more to say. In fact, she was one of several really remarkable and indeed powerful women that we encounter so centrally in the story. George Herbert served the final three years of his life at the small living of Bemerton in Wiltshire (Technically, it was the wonderfully titled Fugglestone-cum-Bemerton). That suggests a real withdrawal from the Court and political life of all kinds, almost an inner exile.

But to return to the seeming mystery of Herbert and the Puritan migrations. As with so much else in the Early Modern period, this can only be understood in terms of his family and his social networks, which included a remarkable number of American connections.

George Herbert came from a very well-connected family, both in literature and politics. His father died early, and his widowed mother Magdalen Herbert was a very important figure in her age (Another of those striking women: does she really not have a full length biography?). She served as muse for John Donne, who was George’s godfather. She was also a major influence on George’s religious development. Lord Herbert of Cherbury, founder of Deism, was one of George’s many siblings.

Magdalen herself remarried Sir John Danvers, who would go on to serve the Parliament in the Civil Wars. He earned notoriety as one of the signers of the death warrant of King Charles I. Magdalen died in 1627, but George remained close to the Danvers family, and it was while visiting them in 1628 that he met Jane Danvers, whom he married.

The Pembroke Connection

But the key name in the equation was Pembroke. George’s family were a junior branch of the mighty Herbert family that became Earls of Pembroke, among the most powerful aristocrats of the time. The first Earl, William Herbert (1501-1570) was a thoroughly Welsh border fighter, if not an outright gangster, “a mad fighting fellow.” His vastly more civilized grandson William Herbert became the third earl in 1601, to be succeeded by his brother Philip as the fourth in 1630. Philip’s wife, Lady Anne Clifford, was a notable literary patron in her own right. Both the successive earls, incidentally, feature extensively in accounts of Shakespeare’s life, and especially in speculations about the identity of cryptic figures like “Mr. W. H.,” to whom the Sonnets were dedicated.

George Herbert was elected to Parliament in the Pembroke interest in 1624. The church living at Bemerton was in the hands of the third Earl of Pembroke, although it was the king who made the actual gift. Bemerton stands just a couple of miles from the Pembroke seat at Wilton. The stunning Wilton House we see presently was built in the 1630s, by Inigo Jones, one of the greatest architects in British history – and, I may add patriotically, yet another Welsh figure in the story. Inigo must have crossed paths with George Herbert, but I don’t know if there is a record of any meeting.

Looking at the two earls, we find many themes relevant to understanding George’s approach in the “Church Militant,” both in terms of religion, and of American settlement. William, the third earl, was passionately committed to the colonization of the Americas. I quote the Dictionary of National Biography:

Pembroke was deeply interested in the explorations in New England. He became a member of the king’s council for the Virginia Company of London 23 May 1609, and was an incorporator of the North-West Passage Company 26 July 1612, and of the Bermudas Company 29 June 1615. On 3 Nov. 1620 he was made a member of the council for New England. His interest in the Bermudas was commemorated by a division of the island being named after him, and in Virginia the Rappahannock river was at one time called the Pembroke river in his honour. In 1620 he patented thirty thousand acres in Virginia, and undertook to send over emigrants and cattle. In January 1622 the council in Virginia promised to choose the land for him out of ‘the most commodious seat that may be.’ On 19 May 1627 he was an incorporator of the Guiana Company. It is said that on 25 Feb. 1629 Pembroke obtained a grant of Barbados, and that it was revoked on 7 April 1629, owing to the prior claims of the Earl of Carlisle, but Barbados was included in a grant to his brother Philip of 2 Feb. 1627-8. From 1614 Pembroke was a member of the East India Company.

Virginia, Barbados, Bermuda, Guiana, New England, the Northwest Passage … this was a sweeping imperial vision.

Philip Herbert, the later fourth earl, participated in most of the same colonial companies and ventures. Both William and Philip appear on the 1609 Charter of the Virginia Company. The Virginia Company kept records of the adventures and shipwrecks of its ventures, and one sensational account in 1609 was picked up by the third earl’s friend William Shakespeare, who used it as his basis for The Tempest.

Through the 1620s, Philip was very friendly with Charles I, with whom he shared aesthetic and architectural interests, but religious issues proved divisive. He supported “godly Protestants,” and was pro-Puritan. He opposed Laud, and often fell out with Henrietta Maria. Although this is beyond the span of the present story, as the fourth earl in the late 1630s he became a real enemy of the Court, and was a leading Parliamentary figure during the Civil Wars. Even so, he belonged firmly to the moderate religious camp, and was a fierce enemy of the Puritan radicals.

I won’t go into this here, but sometime I should chat about the seventh Earl (1653-1683), described amicably in Wikipedia as “a homicidal maniac and convicted murderer.” But that is another story.

The Virginia Company

So far, I have talked about George Herbert’s references to America. But the “Church Militant” never mentions New England, and there were other parts of America in which contemporary Britain – and the wider Herbert family – had its interests.

I have already mentioned the heavy Pembroke involvement in the Virginia Company, but George Herbert was close to several people intimately connected with that body. By way of background, that Company had four successive charters between 1606 and 1618, but it faced growing factional crises from the late 1610s, and the Jamestown Massacre of 1622 caused a terminal crisis.

Significantly in terms of modern-day discussions, one divisive issue in 1619 involved the famous arrival of the first ships importing slaves to English territory – hence the controversial 1619 Project that has been so much in the news in recent months. One Company faction, led by the Earl of Warwick, favored such adventurous enterprises, while the rival group led by Sir Edwin Sandys was much more dubious. That was not a debate over the morality of slavery, but rather about risk-taking and the potential of get-rich-quick schemes, as opposed to long-term settlement.

I do stress that factional division, as I will be returning to it, and particularly Sandys’s followers. Sandys found another enemy in King James. In 1624, the king dissolved the company and made Virginia a royal colony. George Herbert’s stepfather Sir John Danvers was highly active in the company throughout, and in 1624 he organized the copying and rescue of the Company’s records.

Herbert connections in the Company abounded. George’s first cousin was Edward Herbert of Aston (1592-1657), another MP and firmly part of the Pembroke political network, his affinity. In 1619, Edward became legal counsel to the Virginia Company, probably at the recommendation of Sir John Danvers. It was the need for parliamentary support for the Company’s efforts that led Edward into Parliament in 1621.

The Ferrars and Little Gidding

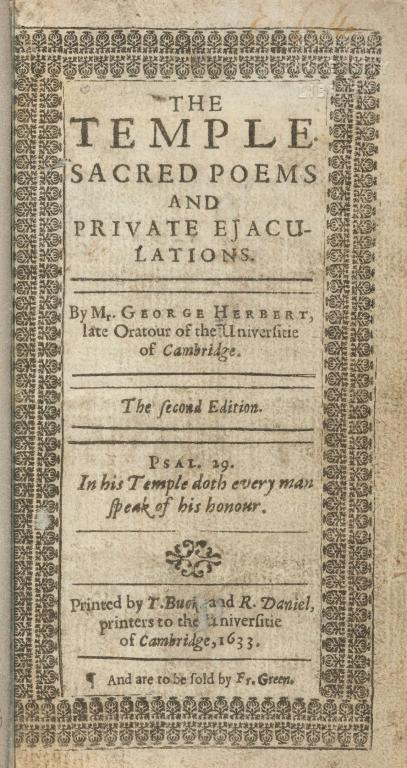

Also heavily involved was the Ferrar family. The merchant Nicholas Ferrar the Elder (1546-1620) had wide and indeed global trading interests, and he was an early investor in the Virginia Company. Among his sons were John and Nicholas Ferrar. John Ferrar (1588-1657) served as the Company’s deputy governor and treasurer. In the mid-1620s, the younger Nicholas Ferrar (1592-1637) was heavily engaged in political and parliamentary struggles growing out of the Company’s activities. As I have said, Nicholas was the intimate friend of Herbert who arranged the publication of his great collection of poems in The Temple. The two first met in their Cambridge undergraduate days.

The Ferrar family suffered disastrously from the ruin of the Company. At the end of the decade, like George Herbert, Nicholas withdrew from public life and turned to private piety. In 1626, Nicholas was ordained a deacon – by Bishop Laud – and he transformed the property at Little Gidding into a de facto Anglican religious community organized around the Book of Common Prayer. This was the place where, three centuries later, T. S. Eliot would famously tell visitors and pilgrims that

You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.

Critical to all these efforts was Nicholas’s very long lived mother Mary Ferrar (1551-1634), who created the settlement at Little Gidding as a refuge for her family in time of distress. She was in effect the community’s matriarch and mentor. Put another way, a couple of highflyers were left stranded following a corporate meltdown, and their aged parent had to bail them out as best she could. Does that not sound very modern?

Most of the community members were part of the extended family, including John Ferrar. Another key figure was Arthur Wodenoth (1590-1650), the son of Mary’s brother. I quote the DNB:

it was he who arranged the purchase of Little Gidding by Mrs. Ferrar, and supervised the restoration of the neighouring church at Leighton, to which Ferrar’s friend George Herbert had been presented in 1626; with Herbert, Wodenoth became as intimate as he was with the Ferrars. He witnessed Mrs. Ferrar’s will in 1628, was present at Herbert’s death in 1633, and was executor of his will. He was also well known to Izaak Walton, whom he supplied with details of Herbert’s life. It was probably through Ferrar and Mrs. Ferrar’s second husband, Sir John Danvers, that Wodenoth became interested in the Virginia Company. He was not a member till some time after 1612, but he took an active part in the affairs of the company till the revocation of its charter, siding, like Ferrar, with the party of Sir Edwin Sandys against that of Sir Thomas Smith.

(The point about “Mrs. Ferrar’s second husband” is an error). Wodenoth wrote a posthumously published Short Collection of the most Remarkable Passages from the Originall to the Dissolution of the Virginia Company (London, 1651).

But there was a vital religious dimension to all this corporate activity. For all the later interest in the New England settlements, we should also recall that the Virginia Company had a powerful religious justification, at least in theory, and was pledged to evangelize Native populations. Many of the key figures in the Company, like the Ferrars, were devout believers, and within the mainstream Anglican tradition. Nicholas himself is commemorated in the calendar of both the Church of England and the US Episcopal Church.

The Ferrars, like Herbert, were high Anglican, and their activities at Little Gidding excited real Puritan hostility and fear. A 1641 pamphlet offered A briefe description and relation of the late erected monasticall place, called the Arminian Nvnnery at Little Gidding in Huntingdonshire … the foundation is by a company of Farrars at Gidding. Nunnery, monastic … in the Protestant language of the time, these were dreadful accusations. “Arminian meant Protestants who rejected strict and inflexible Calvinism, which according to the Puritan mindset of the time meant that they were little better than outright Catholics.

Returning to The Church Militant

When we read the “Church Militant” then, we should not think of references to a “religious” migration to the New World entirely or even chiefly in terms of Puritanism, or of New England. Mainline Anglicans also had their missionary dreams in those parts.

With that in mind, I turn back to that mysterious passage I highlighted in my previous post about those who had suffered financially, leaving them in something like holy poverty:

My God, thou dost prepare for them a way

By carrying first their gold from them away:

For gold and grace did never yet agree:

Religion alwaies sides with povertie.

We think we rob them, but we think amisse:

We are more poore, and they more rich by this.

Thou wilt revenge their quarrell, making grace

To pay our debts, and leave our ancient place

To go to them, while that which now their nation

But lends to us, shall be our desolation.

It might just refer to the Puritans, but it works much better for people like the Ferrars, victims of the collapse of the Virginia Company. If that is the case, then we might read that passage something like this. The state impoverished those poor believers, but soon, the perpetrators will repent it, as they themselves might have to take refuge in those American parts. The agony occurred in 1624, but it was very much in people’s minds five or six years later, as the Catholic threat grew more intense. Meanwhile, the well-publicized Massachusetts venture revived interest in American settlements, and American colonization.

The “Church Militant” belongs to that moment when George Herbert would be despairing of English politics and faith, and seeking salvation in new ventures to across the Atlantic. To return to that original quote,

Religion stands on tip-toe in our land,

Readie to passe to the American strand….

Then shall Religion to America flee:

They have their times of Gospel, ev’n as we.

In the current TLS, Rebecca Fraser has a substantial review of four recent (all 2020) books on the Mayflower and its era. These are: Francis J. Bremer, One Small Candle: The Plymouth Puritans And The Beginning Of English New England (Oxford University Press); John G. Turner, They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony And The Contest For American Liberty (Yale University Press); Stephen Tomkins, The Journey To The Mayflower: God’s Outlaws And The Invention Of Freedom (John Murray); and Graham Taylor, The Mayflower In Britain: How An Icon Was Made In London (Amberley). Rebecca Fraser herself is the author of The Mayflower: The Families, the Voyage, and the Founding of America (St. Martin’s Press, 2017).

John Turner is my excellent blogging colleague at the Anxious Bench.